Can a carnivore be a vegetarian – research on the Pleistocene cave bear

A quiet homemaker, occasionally forced to wrestle without any rules. An avid vegetarian, for which he paid the ultimate price. An object of worship whose smell could be smelled from miles away. We talk about the Pleistocene cave bear inhabiting the Bear Cave in Kletno – because it is the bear in question – with dr hab. Adrian Marciszak, prof. UWr.

Ewelina Kośmider: The article “Fate and preservation of the Late Pleistocene cave bears from Niedźwiedzia Cave in Poland, through taphonomy, pathology, and geochemistry,” published in Scientific Reports, which you co-authored, presents an interdisciplinary study of the population of the cave bear Ursus spelaeus ingressus inhabiting Niedźwiedzia Cave.

dr. hab. Adrian Marciszak, prof. UWr, Department of Paleozoology, Faculty of Biological Sciences: The Bear Cave is a model example of how interdisciplinary research can be conducted. Ever since its discovery in 1966-67, this research has been of this nature – covering a whole range of different types of analysis. The Pleistocene cave bear lived in a specific environment, so in addition to the paleozoologists who analyzed the condition, morphology, dentition of the bears, geologists are also involved in the research, who explain to us what processes influenced the very formation and formation of the cave. We have scientists studying isotopes that allow us to answer questions about what the bears ate, what their living environment was like, what the climate was like. Palynological studies are very important, because many of the plants that are found today also grew during the Pleistocene period. The cave bear was an almost exclusively herbivorous species, hence it was very strongly influenced by vegetation. We also have people involved in the study of tafonomics, or reading traces from animal bones. From tafonomic analyses, we can find out what was the cause and nature of the injuries visible on the bones, and thus make a thesis about what was happening to the animal in question. And, of course, genetic studies that allow us to find out when this animal came to an area, what were its ancestors, what were the dynamics of the population, how did it evolve?

What is targeted therapy?

When an animal eats food, it accumulates different proportions of carbon and nitrogen in its bones or enamel. By examining the basic proportions of these elements, you can find out whether the animal was more herbivorous or carnivorous. In the case of the cave bear, we have clear confirmation of what we already know from other European or Asian sites, that cave bears were 99% herbivorous, which is exceptional for such large predators. During the “prosperous” period, when the growing season was long, it was very beneficial for him. On the other hand, with climate change, the emergence of competition in the form of other herbivores, this proved to be a drawback. The cave bear led a more sedentary lifestyle and did not undertake migrations over such long distances as the brown bear, while, relying on one type of food, it was limited.

So was the cave bear’s vegetarianism the cause of the species’ extinction?

The reason was specialization toward vegetarianism, but also competition from the brown bear, with which he lived in the same environment. And the brown bear was such an example of a total opportunist – it ate everything, lived everywhere. It had a high availability of high-protein animal food and competed with the cave bear for caves. Male brown bears have eaten cave bear cubs and also killed adults. And when the male brown one had eaten and slept in the Bear Cave, he would get down to “other things,” there would be interbreeding between the two species. Unfortunately, the genetic incompatibility was such that the cubs that arose from such relationships did not live to adulthood. After two or three years, they died due to genetic defects.

Previously, there were hypotheses that primitive man was a threat to the cave bear, but your research did not confirm this?

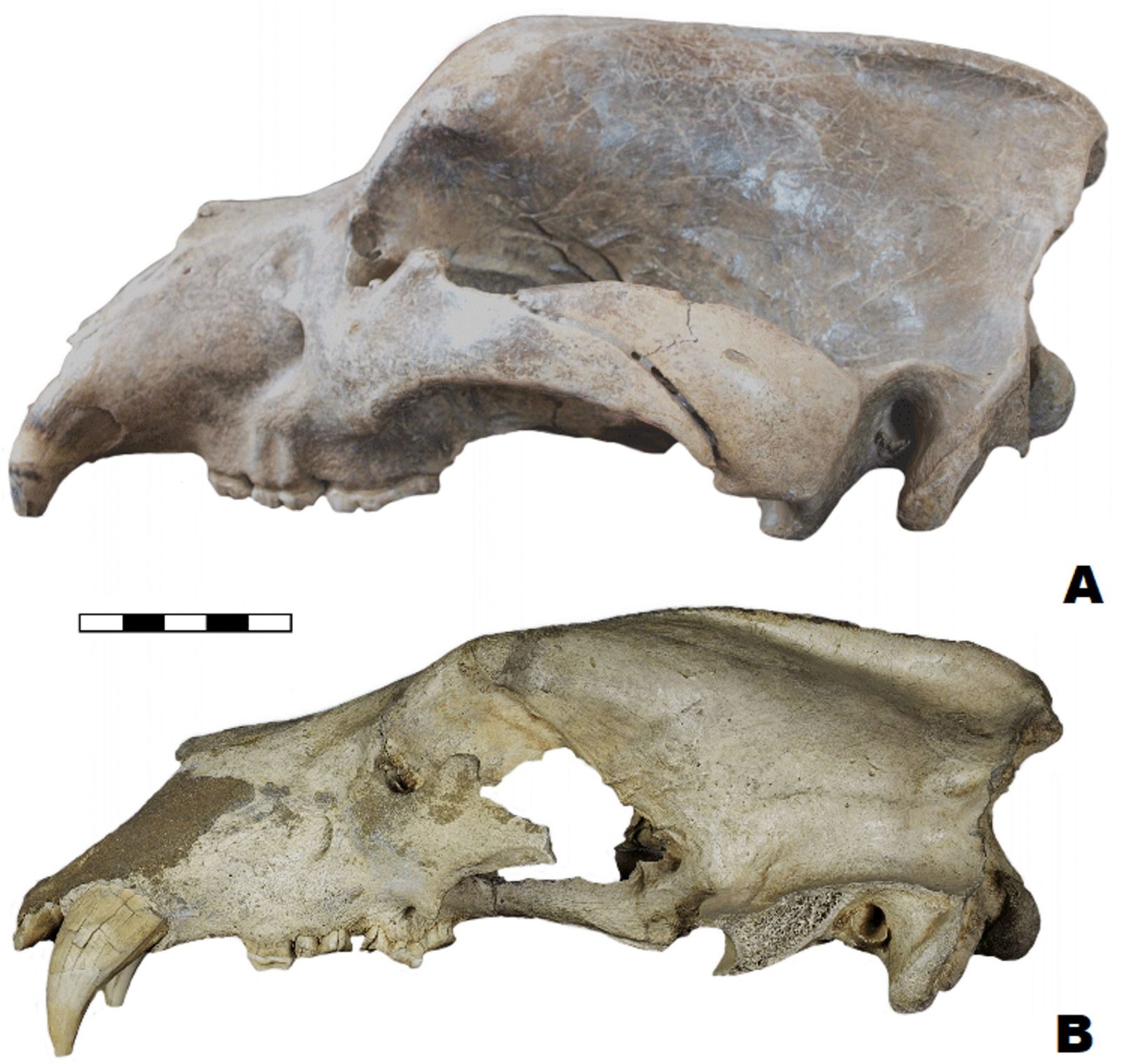

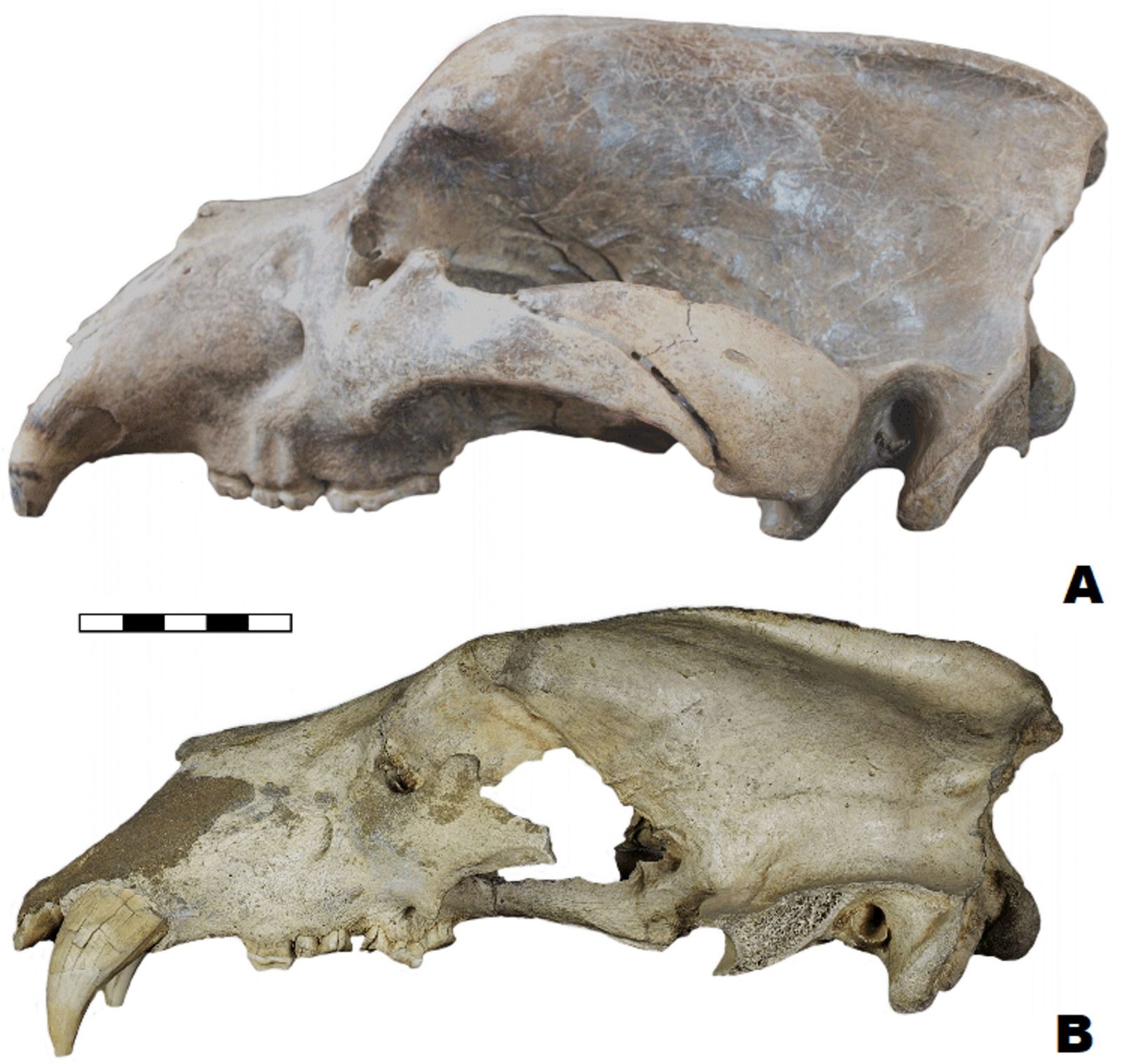

As for the cave bear, man’s role in its extinction is nonetheless not insignificant. However, no direct confirmation of human presence has been found in the Bear Cave, or in the caves of the eastern Sudetenland in general. We know he was there because there are archaeological sites, but no human remains have been found. Our research also did not find a single piece of evidence that humans left any cut, crushing or impact marks on the cave bear. Bear circles with blades or fragments of stone blades embedded in them have been found in caves in Germany, such as in the Swabian Jura. For a long time, based on some of the finds from Bear Cave, such as the skull of a young bear with two holes in its front end, the belief operated that many bear injuries were inflicted by the hand of man. However, our tafonomic analysis showed that these are probably bite marks from the tusks of a lion or steppe (brown) bear. There are still numerous transverse, shallower cuts on the skull. This was interpreted as human filleting. However, they are most likely the remains of claws that a lion or brown bear drove into a cave bear in an attempt to grab its head and hold it down to then bite it on the spine.

Did you come to this conclusion by comparing this skull with posts from other sites?

Yes, these types of comparisons are done in such a way that, first of all, we refer to modern animal behavior, and sometimes experiments are done on bones that are cut. Comparisons with other positions are also being made. We have finds also from Poland, where human influence is evident, it is said, in a case of bear worship: there are clear traces of sawing, cutting, chopping bear bones. For example, in the caves in Jura Krakowsko-Czestochowska, such as the Cave in the Towarny Mountains or the Krakow Spadzista site, where there are also bear tracks with clear cuts.

Cave bears were not specimens of health, plagued by numerous diseases like osteoporosis, ringworm, spinal disease and tuberculosis. All this can be investigated just by paleopathological analysis?

Exactly yes, it’s all visible in the bones. We have a great many examples of various types of degeneration on joints, metacarpal bones, phalanges, long bones, which clearly show that the population from the Bear Cave in Kletno was not a healthy population. This was certainly largely influenced by the harsh climate of the Sudetes and the high humidity of the cave. We have a very high mortality rate of juveniles. Today, the brown bear in the environment lives an average of 20 to 30 years. The average life expectancy of cave bears, it was calculated, was 8-10 years, and it should be twice as long. It is very understated by juveniles. We have tens of thousands of bones of juveniles that, on the one hand, perished during hibernation, when the female had no food, and on the other due to poor climatic or environmental conditions. The cause of death was also likely attacks by predators: lions and wolves.

What was the life of this animal like from birth to death? He spent most of his life in the cave where he was born?

Yes. He was attached to his birthplace. These bears very rarely migrated, if they did, it was usually only the males. They lived and died in the same valley, possibly nearby. It began as it always does: a meeting between a male and a female. A short mating period of three weeks. The female gave birth during the winter. After a pregnancy of several months, two to three cubs were usually born. The bears spent the first few months with their mother in a roost, coming out around April, when vegetation starts. The first years of their lives were spent together with their mother. Cave bears in general lived not so much in herds, but in such loose communes. They would congregate in a single cave, especially for the hibernation period, to increase their safety. The bears’ lives were divided into two phases, namely six months of hibernation and six months (April to October) of intense foraging – males could weigh up to a ton before winter. In the caves for the hibernation period, they tried to choose places that were more difficult to access, which could end up with them getting stuck. Their life was not very dynamic, it was – unlike, for example, the brown bear – a quiet life of a householder.

What other differences were there between the brown bear and the cave bear?

The main difference, was that the brown bear had a flat forehead, while the cave bear had a convex one. Living in caves, the cave bear inhaled much colder and more humid air, so it needed large bays to warm that air for it. The cave bear had a proportionally smaller number of teeth, and they were much larger, wider and flatter so that it could more easily rub plant food. He also had a larger head relative to his body size and was more barrel-shaped. This was due to the fact that, eating plant food, he produced a very large amount of gas and was perpetually walking around bloated. Such a herd of sleeping dozens, hundreds of bears could be sensed from as far away as thirty kilometers.

As many of them lived there at one time?

Knowing the size of Bear Cave today and knowing that it is more than five kilometers long, it could have been inhabited by two or three hundred individuals at one time. We are talking about adult bears spread out in different parts of the cave. They lived in a loose cluster on the one hand, but on the other hand alone, without much hope of help from other individuals in case of attack. It was more like a commune than a society. There wasn’t even a full family, just a female and cubs. The male did not feel his paternal duties, because it is often the case that the female has more mating partners than one, and likewise the male has more female partners, so he is not even sure if it is his offspring. The cave bear was less aggressive than the other species, but very large – the female weighed 300-500 kilograms, the male from 500-600 kilograms to 1 ton. So he didn’t have many opponents, because even a lion or a human had to think twice to attack such an adult bear.

But assaults by other predators, as you write in the article, while perhaps not rational, did happen?

Usually the attacks were carried out by large adult male lions that could handle a bear. However, confrontations often ended in injury or death to the lion – we have quite a few remains of male lions in the Bear Cave.

The paleopathological analysis you conducted consisted of examining fossilized bear tissues. You found inflammations and abscesses that resulted from attacks by other predators. Such inflammations indicate that the bears did not die immediately after the skirmish, but after some time as a result of infection?

This was the case in the case of the young bear I mentioned earlier, described by our colleagues, which we supplemented with an interpretation. I will explain how lions hunted bears. A bear is not typical prey for a big cat, as the cat’s way of killing is to turn over a buffalo or antelope, grab it by the throat and strangle it. The hoofed animal, knocked over and unable to fight, is overpowered by the lion. The bear, on the other hand, has very mobile paws with powerful claws, and if the lion wanted to strangle the bear in this way, the bear could kill it. For this reason, the lion tried to grab the bear’s head with its front paws, bite at the base of the skull between the first and fifth cervical vertebrae and thus kill it. Everything was happening in the dark. It was total wrestling, without any rules. This young female, whose remains we analyzed, was attacked by a lion and bitten very deeply. The bear survived, but there was inflammation in the body. The wounds healed for several weeks, but eventually the animal died, most likely as a result of this infection.

How long did the bears use the cave in Kletna?

Cave bears used a given cave for a long time, in the case of Bear Cave it was 50-60 thousand years.

When and why did they become extinct?

As early as about 30-28,000 years ago, cave bears began to disappear in Spain and the British Isles. The same is observed a little later in the rest of Europe – in times of a cold climate regime and limited vegetation, bears have more difficult access to food, which translates into lower reproductive success. Females have little milk, the young are more likely to die. This is compounded by increased pressure from predators and humans. There are fewer other potential victims, so predators focus on bears. And all of this is causing these populations to begin to decline. In many areas, there is no genetic exchange, so inbreeding is created. Hence, recent cave bears are often dwarf individuals, which are often wrongly considered by some to be separate species. Well, along comes the Last Glacial Maximum, which is a very long period of very cold climate after which we no longer encounter cave bears on European territory. We date the youngest specimens at 24-23.5 thousand years. If the cave bear could adapt to changing environmental conditions, it might have survived. Like the brown bear, which, as the climate warmed in the Holocene – when herds of large ungulates ended, meaning easy availability of protein – simply shrank in size and today we can find it in the Carpathians.

Publication reference:

Publication authors: dr hab. Adrian Marciszak, prof. UWr, Faculty of Biological Sciences; prof. dr. hab. Paweł Mackiewicz, Faculty of Biological Sciences; prof. dr hab. Ryszard K. Borówka, University of Szczecin; Chiara Capalbo, University of Florence; Piotr Chibowski, University of Warsaw, dr. hab. Michal Gąsiorowski, Institute of Geological Sciences, Polish Academy of Sciences; dr. hab. Helena Hercman, ING PAN; dr. hab. Bernard Cedro, University of Szczecin; Aleksandra Kropczyk, UWr Faculty of Biological Sciences; dr Wiktoria Gornig, UWr Faculty of Biological Sciences, dr. hab. inż. Piotr Moska, Silesian University of Technology; dr. hab. Dariusz Nowakowski, Wroclaw University of Life Sciences, dr Urszula Ratajczak-Skrzatek, UWr Faculty of Biological Sciences; dr Artur Sobczyk, UWr Faculty of Earth and Environmental Sciences; Maciej T. Sykut, Aarhus University; dr Katarzyna Zarzecka-Szubińska, UWr Faculty of Biological Sciences; dr hab. Oleksandr Kovalchuk, UWr Faculty of Biological Sciences, Zoltán Barkaszi, State Academy of Sciences in Ukraine, dr hab. Krzysztof Stefaniak, prof. UWr, UWr Faculty of Biological Sciences; Paul P. A. Mazza, University of Florence