The GeoBaltic Adventure expedition has come to an end… but this is just the beginning!

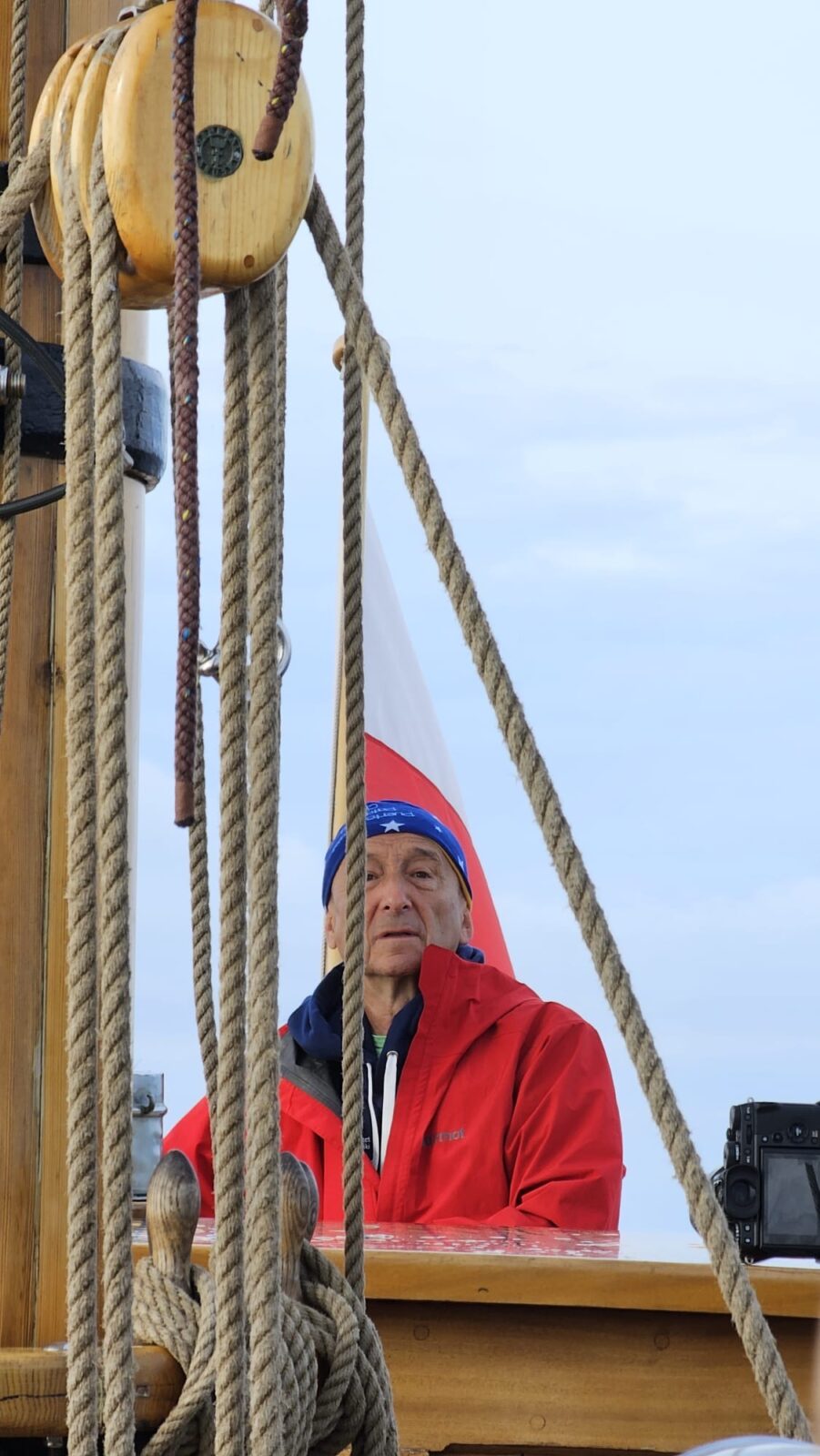

The full-sea twelve-day Baltic expedition of the UWr Geoscience Student Scientific Association is over! The scientific adventure aboard the sailing ship Generał Zaruski, the ‘GeoBaltic Adventure – Sailing Through Time’, ended in Świnoujście on 15 August 2024. Research is now beginning on the basis of the materials collected during the voyage.

The main objective of the expedition, under the patronage of UWr Rector prof. Robert Olkiewicz and the foundation Science. I like was to learn about the geological structure of the Baltic coast from the Precambrian to the present day. The organisers of the expedition also hoped that living and working together on a sailing ship would provide an opportunity to shape students’ soft skills, so important in today’s world. The participants of the expedition therefore set themselves ambitious goals, both scientific and educational. One of the members of the 25-strong crew was dr Tomasz Rożek, one of Poland’s leading popularisers of science.

The crew, still full of excitement, reports

The students and scientists embarked in Szczecin during the finale of the Tall Ship Races 2024, where they promoted our University by bravely performing gangway watches and affixing stamps to tourists visiting the yacht. They also had the opportunity, courtesy of Commander Captain Rafał Szymański, to visit the Dar Młodzieży frigate.

5 August 2024

And so, after the first mutual recognition, the STS Generał Zaruski went to sea with the UWr crew on board. The University of Wrocław flag was raised and the pilot station bid farewell to the ship with the playing of the Dąbrowski Mazurka. Already at sea, the crew were given safety training and familiarised with the rules of watchkeeping and sail handling.

It was a great experience to sail side by side with the biggest and most beautiful Polish sailing ships, including Dar Młodzieży, Fryderyk Chopin, Pogoria, Kapitan Glowacki, during the first joint photograph under full sail of all the biggest Polish sailing ships in many years.

6 August 2024

After wiping away our tears and parting with our sailing company, we set course for Rügen. Sailing against the wind, we arrived there on 6 August. In Sassnitz, on the Jasmund peninsula, the first geological adventure began. We learned about chalk rocks and sediments of the Pleistocene glaciations. During a geological visit to Jasmund National Park, we observed traces of glacial activity in the form of large-scale glacitectonic deformations. We took samples and learnt about the genesis of flints with unusual shapes that occur within the carbonate cliffs.

The second site we visited on Rügen was the Dwasieden cliff, whose sediments record unusual phenomena related to the presence of Pleistocene ice sheets. It was here that we were able to experience how to recognise traces of ancient earthquakes, glacial floods or the melting of icebergshttps://ing.uwr.edu.pl/stanowisko-sassnitz/.

8 August 2024

After leaving Sassnitz, we took a course west and then north. In bad weather, in rain and with a big wave, the sailing ship entered the Great Belt Strait to arrive in Aarhus after 16.00 on 8 August.

On this leg of the voyage, sailing in difficult conditions, we experienced both seasickness and the first hardships of operating in a small space and living in watch mode – ‘you sleep, not when you want to, but when you can, and for a short time’.

Aarhus is the city where Nicolaus Steno lived – one of the ‘fathers of modern geology’, who formulated the superposition principle familiar to all students. The city is home to the university’s Steno Museum, which commemorates him. We also visited the Department of Geosciences at Aarhus University, which is one of Europe’s leading centres for earth and environmental sciences https://ing.uwr.edu.pl/stanowisko-aarhaus/.

We had to say goodbye to Aarhus already in the evening and sailed towards Zealand the same day.

9 August 2024

On this day, we were sailing in a downpour and strong winds of up to 6 on the Beaufort scale, which made life difficult for the navigational watch. In spite of these hardships, it was after 3 pm when the conditions improved somewhat – the outlines of the Danish capital Copenhagen appeared before our eyes.

In Copenhagen, we took a geological tour of the city centre, during which we recognised the rocks that the city’s representative buildings are made of and saw a 20-tonne fragment of the iron meteorite Agpalilik, which was found in Greenland and is now on display at Copenhagen’s Natural History Museum https://ing.uwr.edu.pl/stanowisko-kopenhaga/.

From Copenhagen we sailed south along the coast of Zealand.

10 August 2024

… we stopped in the harbour of Rødvig. This inconspicuous village hides a real geological gem – the Stevns Klint cliffs. What is unusual about this place? We have sampled rocks here that record one of the most dramatic periods in Earth’s history, the geological boundary between two eras – Mesozoic and Cenozoic, formed about 66 million years ago. This period is linked to, among other things, the great Late Cretaceous extinction, during which about three-quarters of all species alive at the time became extinct.

One hypothesis explaining such significant changes on Earth is the implosion of a large meteorite in the vicinity of today’s Yucatán Peninsula, whose environmental effects covered the entire planet. In our research we will be looking, in the samples collected, for micrometeorites that could be remnants of this event https://ing.uwr.edu.pl/stanowisko-stevns/.

It is a unique place for geologists! And we were there!

Late in the evening, after an intense research day, to the rhythms of Perfect, we bathed in the Baltic Sea.

Time was pressing, and there was still so much to see! So we left Rødvig at night and headed east from the island of Zeeland towards Bornholm. While the trip to Rødvig was smooth, the route to Bornholm was a bit of a challenge. Both the navigational watch (a raging wind that almost tore our sail off) and the galley watch (the heeling of the ship did not make cooking either simple or entirely safe) found the sea conditions to be a clusterfuck. In addition, the lack of available berths in Rønne (a harbour on southwestern Bornholm) forced us to turn around and look for safe harbour elsewhere.

12 August 2024

Dusk fell, the sea calmed down and we found a place to moor safely – Hasle, a harbour north of Rønne, it was already Monday, 12 August.

So far we had left ports before 24 hours had passed, but here it was different. So what took us almost two days on Bornholm? What we came for – geological field research.

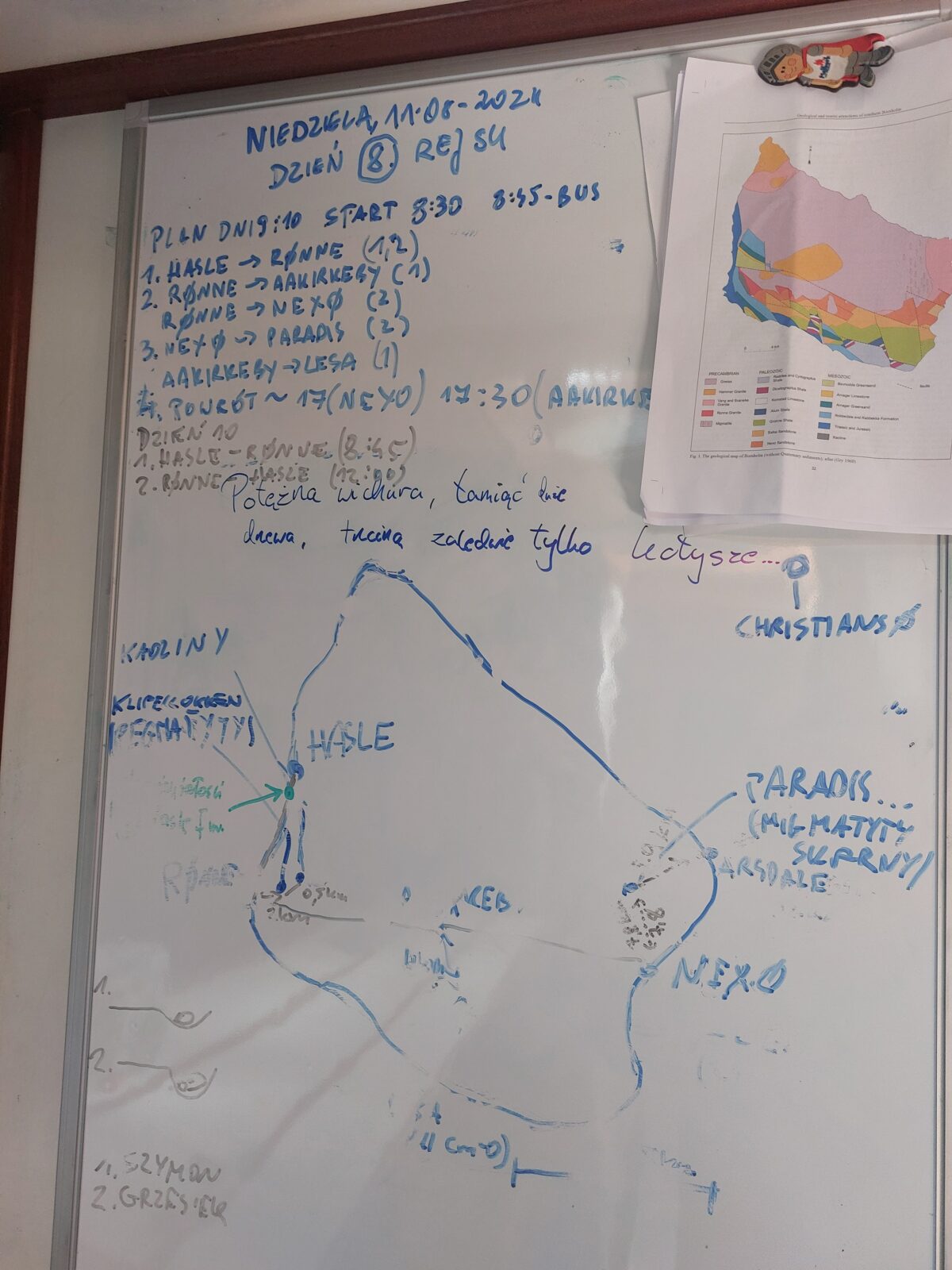

On Bornholm, which is called the ‘pearl of the Baltic’, we visited a number of interesting geological sites, the most famous of which is the rocky outcrop of the Tesseire-Tornquist boundary near the NaturBornholm Museum in Aakirkeby. This boundary divides Europe into two major geological units – the Precambrian East European craton and the Palaeozoic West European platform. It is a unique place where you can simultaneously stand on the rocks of two ancient continents – Baltika and Avalonia, which were formed 1.8 and 0.4 billion years ago, respectively. In addition, during the fieldwork we sampled a variety of rocks, including alum shales for rare metal content studies and bioleaching experiments, Paradisbakkere migmatites and Rønne granites with associated pegmatites for rare metal content studies, and kaolins for potential micrometeorites. We also visited an outcrop of Jurassic sedimentary rocks of the Hasle Formation, where we observed sedimentary structures and searched for fossils https://ing.uwr.edu.pl/stanowiska-bornholmu/.

During the evening rest we had the unusual opportunity to admire another, already non-geological attraction – the aurora borealis and the festival of falling meteors from the Perseid swarm.

13 August 2024

We left Bornholm in the afternoon. After a few hours of sailing we arrived at the Ertholmene archipelago, consisting of three small, picturesque islets: Christiansø, Frederiksø and Græsholm (the latter as a nature reserve is completely inaccessible).

We moored at Christiansø. After many days of sailing and field research, we indulged in a geological, peaceful walk.

14 August 2024

… after 10 a.m., we left the Ertholmene archipelago, setting course for Świnoujście.

And it was a piece of real sailing, in favourable winds, at full seven sails.

After a wonderful day and night at sea, we arrived at the quay in Świnoujście marina around 4.00am.

So much for the crew, still full of emotion, talking about the expedition.

And what was life like for the students during the 12-day voyage?

They worked hard. Apart from the obvious geological work, they performed navigation, gangway and galley watches. They cooked for 25 people in difficult conditions and surprisingly there were even cakes, cinnamons and pies. They learnt nautical navigation, kept a ship’s log, observed hazards and, above all, operated the rigging, which on the General Zaruski provides no facilities. It was not without hands chafed to the bone. Captain Jerzy Jaszczuk’s lectures on maritime navigation were held on board, and Dr Tomasz Rożek from Nauka .To lubię talked about how to communicate effectively about science with different audiences.

Thanks to the favourable weather, the brave attitude of the students and the committed attitude of the permanent crew of the sailing ship, it was possible to achieve the set objectives, the effects of which will be used for many months to come, mainly in the form of scientific publications. Such important student publications for the promotion of science will be produced as the laboratory research progresses. The students now face a stage of serious scientific work and there is no shortage of enthusiasm for this.

The expedition proves that sailing ships can play a training, educational and very serious scientific role, also for university students.

Thank you!

The crew would like to express their heartfelt thanks to Captain Jerzy Jaszczuk, the originator of the geological expedition, whose vast experience and competence, has been and continues to be an inspiration to realise dreams, including scientific ones. We would also like to thank First Officer Adam Walczukiewicz for his great professionalism and educational commitment, Officer Henryk Miszczyk for his passion for geology, his help in engaging students and great contact with them, Officer Filip Kowalski for his sense of humour and shared dog watches. To Petty Officer Mirosław Bielecki, we would like to give special thanks for the care and heart shown to the students and the souvenirs given to us, which will stay with us forever.

The voyage was made possible thanks to the financial support of the UWr Rector prof. Robert Olkiewicz, the Vice-Rector for Student Affairs dr hab. Maciej Cesarz, the Dean of the Faculty of Earth and Environmental Management, prof. Henryk Marszałek, the Director of the Institute of Geological Sciences prof. UWr Anna Pietranik and the Council of UWr Scientific Associations. We would also like to thank Katarzyna Górowicz-Maćkiewicz and Andrzej Baworowski for media and promotional support.

UWr school crew: Marysia Andrzejewska, Szymon Belzyt, Kacper Bieńka, Wojtek Durak, Robert Dybowski, Paulina Góra, Piotrek Krypner, Ola Kupisz, Michał Maciak, Henryk Marszałek, Magda Modelska, Ania Olszewska, Wiktor Paluszkiewicz, Zuza Pilska, Tomek Rożek, Martyna Serafińska, Tomek Starzyk, Ania Tereszko, Mateusz Wolszczak, Grzesiek Ziemniak.