Molecular methods helped to explore the ‘grey zone’ of slow worms

Taxonomy and systematics are among the oldest areas of interest for biologists, who, when describing a new species, not only gave it a name, but each time faced the challenge of assigning it to a suitable group of organisms, indicating the evolutionary pathway that links them.

The most rudimentary method of research was differences in morphology and anatomy between different organisms. It often led to dilemmas – whether the observed differences between populations were sufficient to delineate new species, or whether to separate subspecies, geographical varieties, et cetera – these discussions could last for decades, often until the advent of the era of research using molecular methods.

Taxon1 that well illustrates the story described above is the genus Anguis (family: Anguidae) – slow worm – a legless, snake-like, secretive lizard whose range of distribution extends from the edge of western Europe to the Middle East. In the twentieth, there was a dispute of sorts among researchers working on this group of reptiles, with some arguing for the necessity of distinguishing (at least) subspecies within the genus Anguis, while others claimed that the observed differences between populations were merely a manifestation of geographical variation.

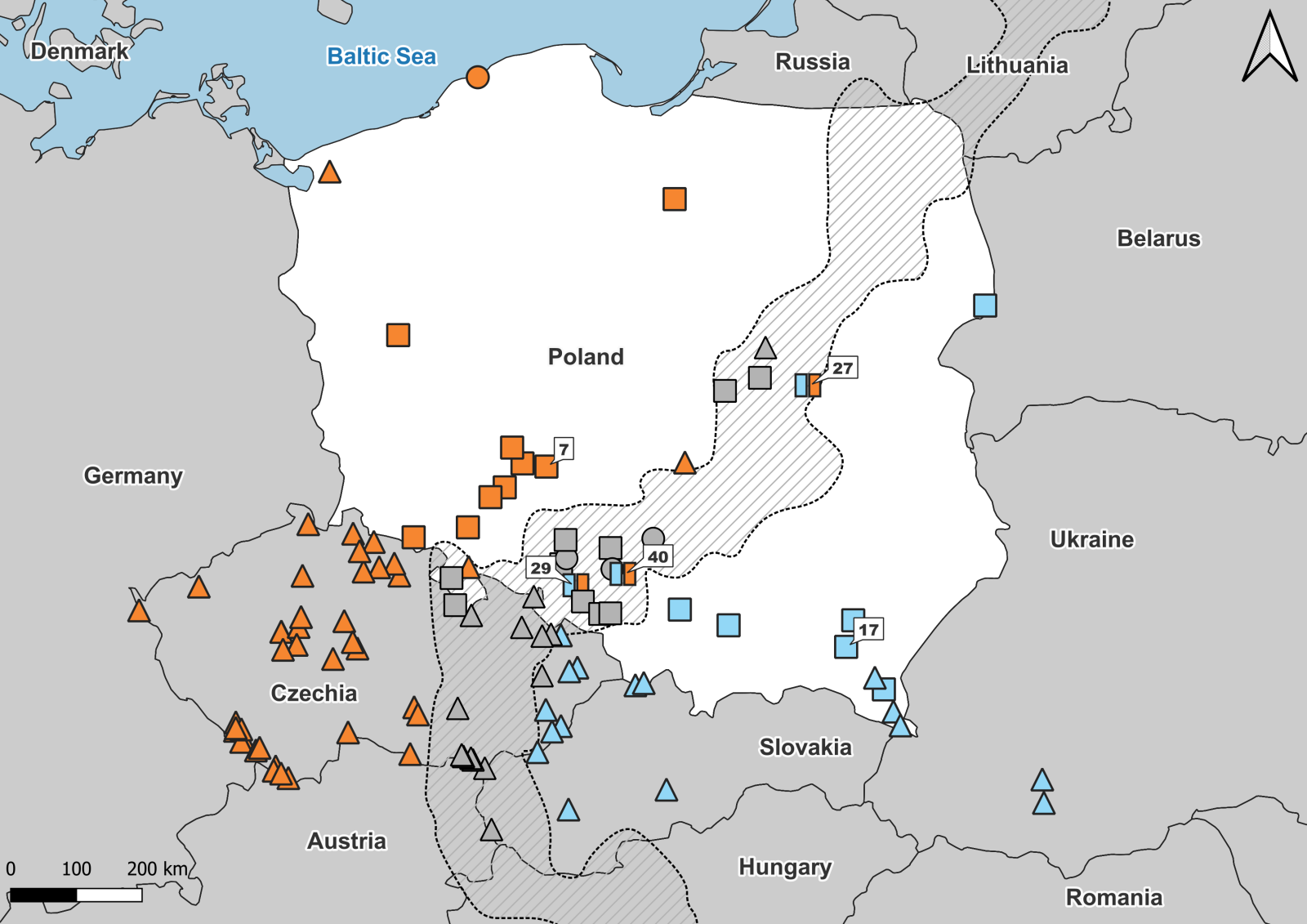

An unequivocal answer came in 2010, along with a paper published by Václava Gvoždík’s team, who using molecular techniques, demonstrated the existence of four species within the genus Anguis, and three years later identified a fifth. From then on, intensive research began across Europe into the range of the individual species and their biological interactions. This has led to the discovery of hybrid zones between individual taxa (e.g. in Hungary, the Czech Republic, and Slovakia), and the publication in 2021 of a paper describing not only the ranges of the individual species but also the extent of the so-called ‘grey zone’ – an area where more than one species of slow worm is suspected to occur. A large part of this area also runs through Poland, for which for years the occurrence of a single species, the common slow worm (Anguis fragilis), was postulated. The situation changed dramatically with the publication of a paper by Gvoždík’s team (2010), reporting the presence in Poland of haplotypes2 typical not only of the common slow worm but also of the eastern slow worm (Anguis colchica). From that moment on, a kind of (albeit unofficial) ‘race’ began between Central European research teams – who would be the first to define the limits of the occurrence of both species and who would discover hybrids.

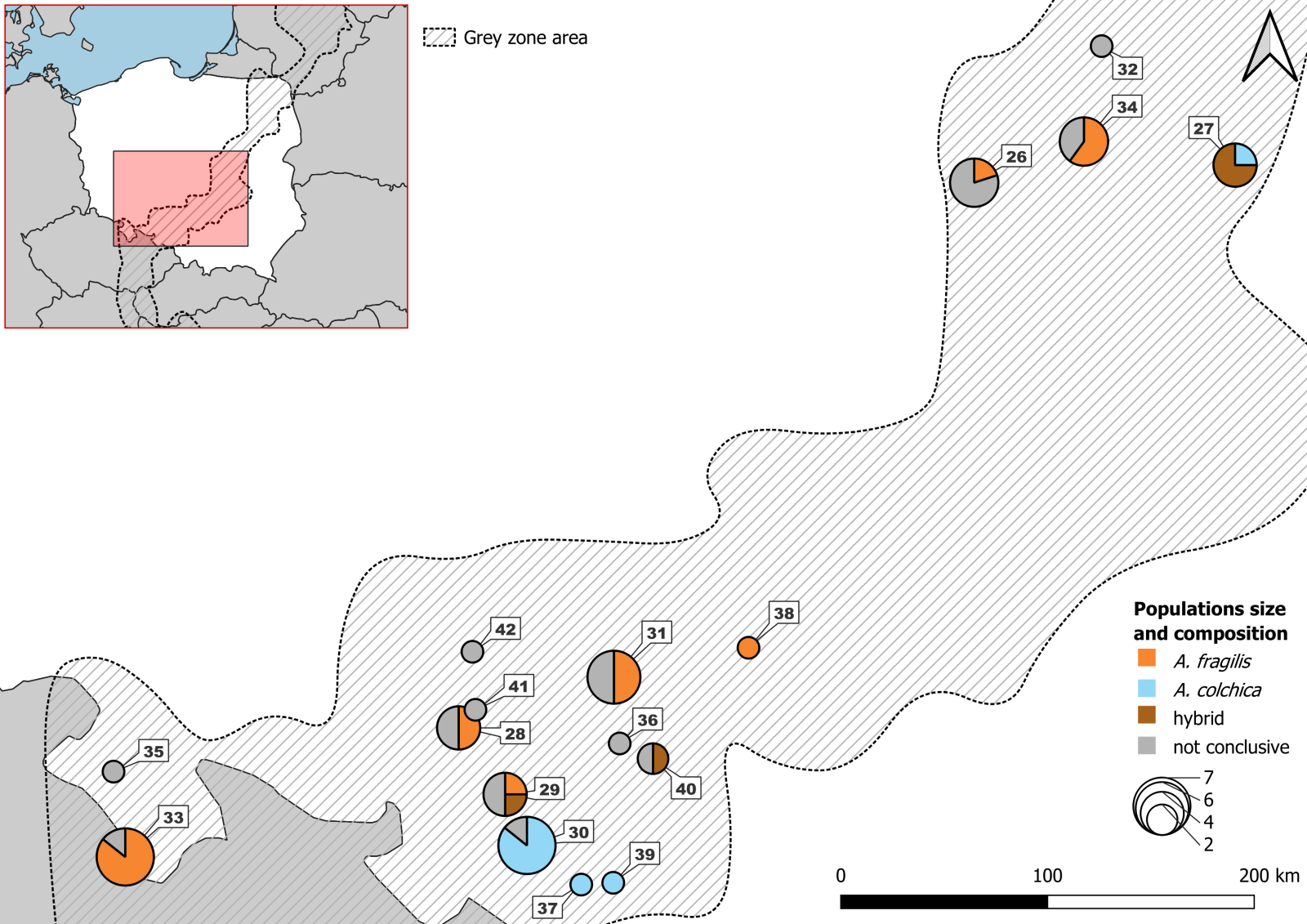

In 2017, two papers on the range of both species were published: the first by dr Grzegorz Skórzewski (University of Wrocław) based on morphological studies and the second by a team led by dr Daniel Jablonski (Comenius University in Bratislava) – based on molecular data. The results of both works indicated Upper Silesia as a place of potential contact between the species and their interbreeding, but the identification of a specific area remained unclear.

The solution to the riddle was published in January 2025 (Skórzewski et al. 2025) in the journal PeerJ. The analysis of 92 specimens from 35 national populations of slow worms, using both traditional methods and molecular biology, not only allowed us to supplement previous information on the distribution range of both species in Poland but also to discover places of common occurrence where interspecific hybridisation takes place. It results in hybrid specimens having the genotype of both species and sharing morphological traits of both. They have been found in the Upper Silesia area and the vicinity of Warsaw – an area previously identified as a fragment of the Polish ‘slow worm grey zone’.

An interesting finding is that the hybrid individuals do not belong to the first generation (F1) of an interspecific cross, but are examples of higher-order hybrids – possibly backcrosses. It means that hybrids of both species of fallow deer retain the ability to reproduce by giving birth to fertile offspring (unlike, for example, the horse and donkey hybrid, the mule, which is sterile and unable to reproduce), and it may be more of an importance for the dynamics of the hybrid zone. In addition, morphological studies have shown that hybrids exhibit a peculiar mosaic of traits of the parental species.

The research obtained does not exhaust the issue of the ‘slow worm grey area’ – many questions remain, starting from the hybrid population structure to competition between species and hybrids for vital environmental resources. A study of the diversity between internal parasites infecting both species and their hybrids is currently underway, and a study of the ecological diversity of all slow worm species using computer modeling methods is being prepared.

1Taxon – a systematic unit of living organisms, e.g. species, genus, family

2Haplotype – a gene group that an organism has inherited from one of its parents

Text: dr Grzegorz Skórzewski, Natural History Museum of the University of Wrocław

Translated by Marcelina Kida (student of English Studies at the University of Wrocław) as part of the translation practice.

Date of publication: 07.03.2025

Added by: E.K.