Watchwords that shaped Poland – a conversation with dr Marta Śleziak

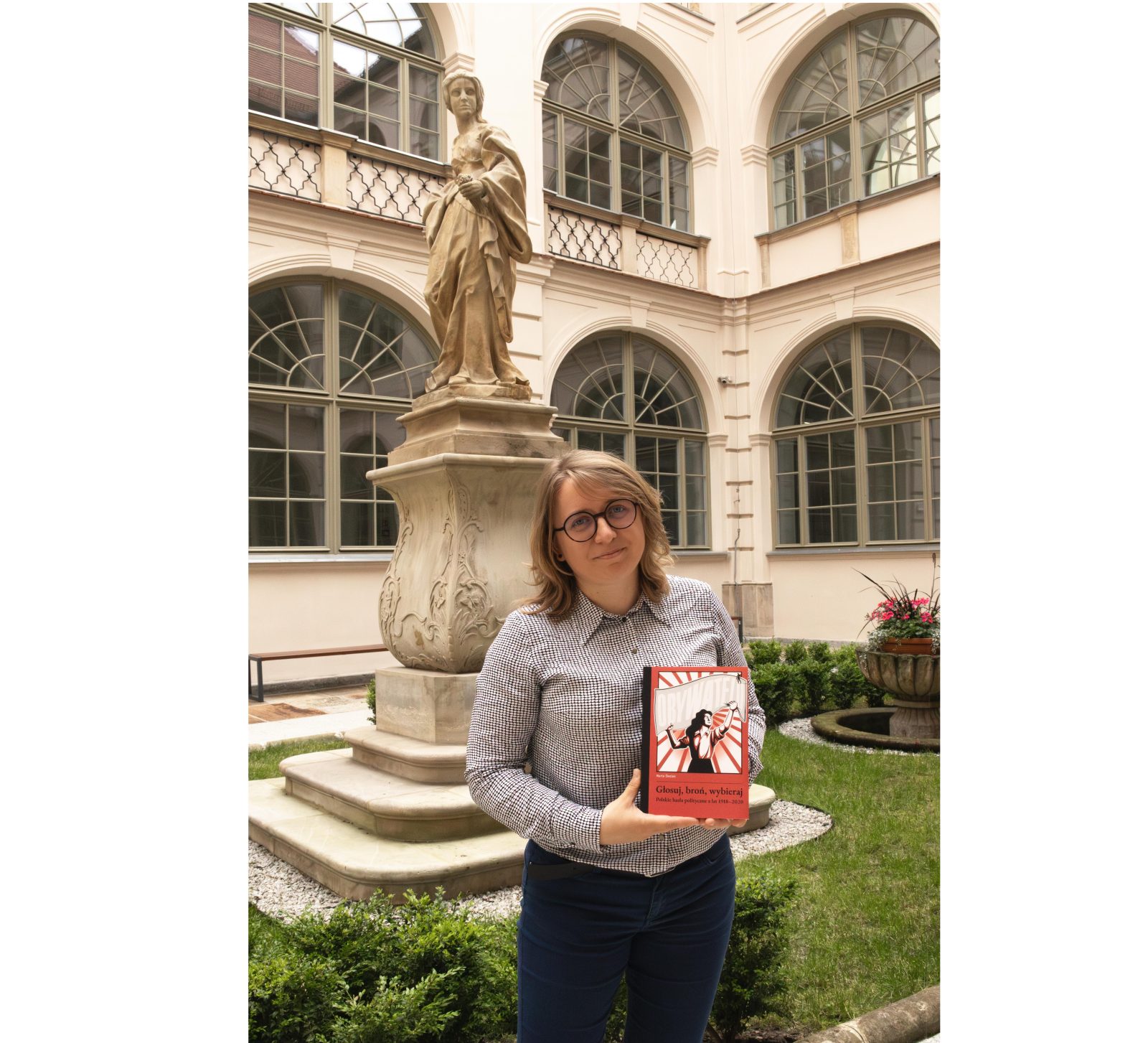

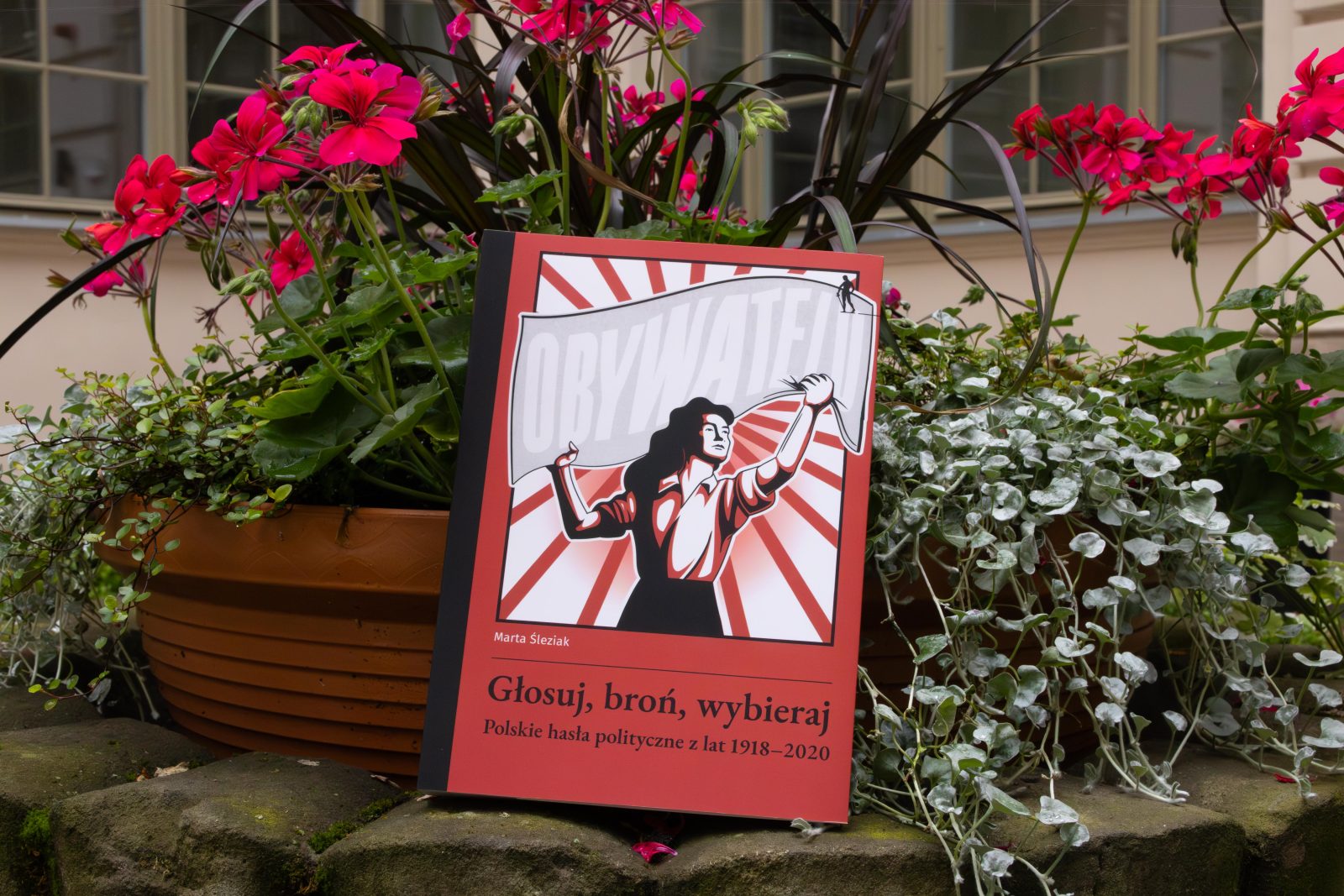

University of Wrocław Press has just released a book by dr Marta Śleziak – “Głosuj, broń wybieraj. Polskie hasła polityczne z lat 1918-2020”. It is a book-compendium, a complement of our knowledge about history and social studies, but, most importantly, about Polish language and how we, as citizens or government, can create all kinds of watchwords and slogans.

We invite you to read the conversation between Maria Kozan and dr Marta Śleziak, assistant professor at the Institute of Polish Studies, who, for years, has been concerned with studying Polish language and popularising knowledge about it, as well as with archiving unique pieces of text, such as Lower Silesian ephemera. The author approaches a truly important and fascinating issue: how brief, usually concise political watchwords not only motivated crowds, but also became a reflection of social moods, dreams, fears and splits over more than a hundred years of Polish history – from the restoration of sovereignty to modern protests.

Maria Kozan: It is not the first time that you consider the topic of politics. In the past, you published multiple academic articles, that can be seen as an announcement of the recent book. What inspired you to taking up the topic of political watchwords as the subject of your studies?

Marta Śleziak: It is a tribute to my several years reflection on watchwords overall. I included the information about what inspired the studies at the beginning of the book – in the notes I recall a memory from the turn of 2018 and 2019, not long after the defence of my doctoral thesis, when in a three-person group – professor Irena Kamińska-Szmaj, dr Marcin Poprawa, and me – we eagerly discussed the language of politics. We were deeply interested in political discourse; it inspired us and was the topic of plenty of our conversations.

It was right then, when I came up with the idea of gathering political watchwords, but in a broader sense. It was important for me to show, how do the watchwords evolve, how do they change, and if their creators replicate well known and reliable words. It was what I was interested in the most, not only the modernity, but also if the watchwords looked similar, for example fifty years ago.

The second important issue, that influenced the book is an attempt to give voice to different social strata and groups. I cared about making it visible, that a political watchword is not only a politicians’ domain. When I was writing my master thesis about the election campaign in 2010, I came across multiple publications dedicated to political language, which clearly accentuated that it is a domain of politicians, journalists and people, who are professionally involved in this field. A political watchword, according to this view, was treated as almost exclusively something, that comes directly from the politicians – what appears on the election rallies, during campaigns, as watchwords typical for the election materials, etc.

But my observations brought a different result. I observed, that when it comes to the function, there is no significant difference between a watchword chanted during social protests and the one, that comes from the politicians. Watchwords chanted by a community, a professional group, protestants and strikers is also put in a political context and has a certain aim: changing the reality in which those people live.

What place do watchwords have in the political communication?

I define a political watchword as a concise, stylistically expressive word form, that is directed at a mass audience and carries a meaning, which is characterised by agitation or persuasion. A part of my research question was if a political watchword can be synonymous with a slogan. I decided to write a separate article on this topic, that was published in ‘Stylistyka’ magazine towards the end of 2024. Based on an analysis of corpora and dictionaries, I proved that ‘slogan’ term is viewed more negatively than ‘watchword’. Slogan is associated with something threadbare, advertising, that has a purpose of manipulating the audience, showing the reality in a simplified, persuasive, often unreal way.

On the other hand, a political watchword is seen as a carrier of sublime ideas, a motivating factor that has barely any negative connotations. This is a view that comes not only from the dictionary definitions, but also an analysis of practical use of these terms. As it turns out, even though in common language the terms watchword and slogan often function as synonyms, there is, in fact, a subtle difference, that we can intuitively catch.

This was the third reason for the book to be created. Following prof. Janina Fras, a researcher at our university, I decided to distinguish a political watchword as a separate genre of a political statement. I think that a political watchword belongs to both the governing – politicians, those who aspire to be in power, political parties – and the communities: professional groups, protesters, strikers, whose activities have a clear political context. And this context is what is important.

To sum up, I could point out three main impulses, that made me write this book. First, the academic community from which I come from, the research on the political discourse at the Institute of Polish Studies. Second, the desire to study the evolution of a watchword and show its duality – how it belongs to both language of the governing and citizens’ objection. Third, the need to demonstrate the political watchword as a separate genre of statement, that is deeply rooted in the political context.

Did any of the analysed historical periods especially surprise you in terms of quantity, quality or functions of the political watchwords?

When our discussions in the academic community started, between 2018 and 2019, an idea emerged of preparing a political watchwords’ dictionary, a lexicon, that would cover a broad representation of political watchwords from different eras. What we cared about was to include watchwords characteristic to various periods in Polish history. So, we distinguished some typical for the last century eras: the Second Polish Republic, Polish People’s Republic and the Third Republic of Poland. The period of war and occupation was already covered by other authors, for instance professor Marcin Poprawa, so we did not include it in our collection. We created a list of key political events of each era. Based on this, we started collecting watchwords, that may, in the future, appear in the political watchwords’ lexicon.

When I started working on the book, I cared not only about showing the variety of collected watchwords, but also how does the watchword itself evolve. I wanted to analyse, where does it start, what motifs, keywords and political symbols are used most frequently, what evaluative language appears most commonly. It was interesting for me, whether the modern watchwords refer to the old ones or there are any tendencies and repetitive structures. For this reason, the collection of watchwords is being constantly expanded by us – we are regularly working on is and aim at its refinement.

And how did this process look in the case of your book?

While working on the book, I chose the elements I considered the most important. From the Second Polish Republic period I chose parliamentary campaigns. They reflected a completely different social reality than the one we know today. For example, there was no election silence back then and the agitation lasted to the day of the elections, which was surprising for me. The key to the choice of materials was looking through press findings and ephemera relating to the chosen events.

In the Second Polish Republic era I picked out three topics: parliamentary campaigns, Polish-Soviet war (essential because of the social mobilisation and unity of nation against the common enemy – the Bolsheviks) and plebiscite campaigns in the Upper Silesia. I wrote about the last topic in an article before, but I enhanced the perspective and compared these three areas.

From the Polish People’s Republic, I focused on the threads, I considered particularly interesting from the language point of view on the watchwords. I did not want to follow the beaten paths, because the literature on the period is already rich. I chose topics that were typical for the watchwords, such as: people’s referendum and Legislative Sejm elections, economic plans, way of talking about ‘kindred nations’ or enemies of the system, for example the Catholic church, Zionists or so-called reaction.

In this chapter I also included countrywide strikes, that were particularly important for me because of their social character. Those strikes were full of watchwords, and the analysis of their language has shown, how these watchwords can be shortened and simplified in cases of fighting for citizens’ rights. I also decided on separating the breaking moment – 4th of June 1989 elections – that allowed us to see, how does the campaign look like from both the coalition government and Solidarity.

Finally, regarding the Third Republic of Poland, I chose three key areas: parliamentary campaigns, presidential campaigns and social protests. Even though the protests do not take up a lot of space in the book, they are especially important for me, and the material they cover turned out to be crucial for the whole writing. This way, the material in the book spread over a hundred years, covering different forms and contexts of political watchwords.

Talking about those protests, which you wrote about less, but I think that either way, the thread of women participating in creation of Polish political watchwords in the XX and XXI century is worth mentioning. What changes in activity and watchwords of women, observed in the period you were researching, say something about their role in Polish public and political discourse?

In 2020 we were involved in the events of the Women’s Strike. Women were going on the streets en masse, demanding their own rights. I remember multiple watchwords, that appeared on banners and other materials – they were a sign of social objection and determination of those, who took part in the protests.

In 2016, during the wave of protests and the Women’s Strike, and then in 2020, there were a lot of voices saying that women’s anger was unprecedented and the watchwords were unique, one-of-a-kind. And they were, in fact, because of their creativity, but at the same time, they had their past counterparts – for example, year 1989 and watchwords of women, who protested the abortion ban, that could as well appear on modern banners. Expressing your opinion through the watchwords alone is nothing new. I had a similar impression while analysing the watchwords of the ‘Orange Alternative’ from the 1980s, that were unusually ironic, sarcastic, that were wordplays and included intertextual references. Even though the times changed, the irony sounds familiar to the watchwords of the 2020s.

Regarding the women’s watchwords, I was surprised to see, how did the nature of these forms change: how they went through colloquialization, or otherwise – intentional archaization – how they started to use vulgarity as a tool of expression. As a linguist, I am not judging, if it is a good thing, right or aesthetic; I think that vulgarisms are an important part of the language. Their function and the strength of expression have a massive meaning in the context of social communication. If nobody considered those watchwords important, they just would not appear. If the language of these messages went through this vulgarisation, there was an individual, personal reason, inspired by the social and socio-political circumstances. There had to be a kind of trigger, that caused the watchwords to take this form. In the book I quote views of linguists, who presents two sides of this issue. Some of them justify this tendency and consider it a valid reaction. The others are, on the other hand, convinced, that vulgarisms should not appear in the language of public space, because it does not match the debate culture. What is interesting, after facing the allegations of being too vulgar, the watchwords were modified and replaced with neater alternatives, what shows an unusually high language consciousness of Polish language users. For me, it is also a proof of incredible plasticity and broad potential of language.

In your book, you mention, in detail, the planned excerption of material, that you did with accordance to the rigoristic rules of academic writings. How did the process of collecting and selecting the analysed watchwords go? What press, historical or visual sources did you consider essential?

When I built the list of most important events, that I wanted to highlight, I chose the sources in the way that would present a certain phenomenon as broadly as possible. For example, in the case of the Second Republic of Poland I considered press materials that represented different sides of political scene: left-wing, right-wing and centrist publications. I gave a lot of attention to the parliamentary elections. I do not have my notepad on me now, but I wrote down a lot of magazine numbers there – I noted, what I analysed and what needs to be analysed yet.

I bow to everybody who create and operate digital repositories, because they saved me a lot of time. Thanks to them I did not have to create queries only at the libraries, but I could also use the digital press collections. I am incredibly thankful to everybody, who digitalises the materials and cares about their availability.

When it comes to the Polish People’s Republic, when I, for instance, used the Polish Film Chronicle materials or archival photography, the repositories also played a significant role. I used the historical sources, books about certain events, where the watchwords were usually cited as well. I also visited the European Solidarity Centre in Gdańsk to go through archival materials and see how the reporters registered important events. It is where I came across banners from the period of June elections in 1989. For me, the albums were helpful, as well as various historical coverages.

In the case of the Third Polish Republic, I worked with political science publishing houses, that distribute election materials (e.g. programs of political parties or candidates for president), press and internet reports, as well as traditional newspaper and photographical reports. I tried to include both perspectives, social and political, the same with different political orientations. I cared about presenting as diverse variety of watchwords as possible. I hope I succeeded.

I know that in the Institute of Political Sciences there are collections of leaflets from past and present electoral campaigns. Later, they are used for analysis or simply as an element of one’s own material database. Maybe something like this does really exist, because, during one of the last campaigns, someone mentioned that if I find any leaflets in my hometown, I should collect them and contribute to their collection.

It happens that when someone knows that a person is interested in a topic, they start to supply them with materials. It was the same with my wonderful students. During the Practical Stylistics course, when a discussion on political watchwords started, my groups, knowing that I collected them, turned my attention to some interesting examples. It was truly fascinating.

The intensive work on the book itself, I mean, the writing, lasted for a year, but the preparation, collecting the materials and analysing them, lasted a few years: from 2018/2019, to sending the book to the publishing house. It was a long, but very inspiring process.

In your book, you highlight multiple times, that the political watchwords not only reflect the social reality, but can also shape it, provoke to action, awake emotions, integrate or antagonize. Can you point out some examples, that, in your opinion, influenced the course of political events or permanently affected social consciousness of the Poles? I mean both the classic formulas, like “God, Honour, Fatherland” (Bóg, Honor, Ojczyzna) and “Workers of the world, unite!” (Proletariusze wszystkich krajów, łączcie się!), as well as the modern ones, chanted on the streets during the protests. What do you think about their communicational efficiency? Can a watchword be a spark of a change, not only its reflection, and if so, when?

The watchwords have always played a significant role; they were a depiction of individual and collective attitudes and emotions. In January 1919 the citizens of Warsaw welcomed Ignacy Paderewski chanting “Welcome, the bearer of might and power!” (Witaj, zwiastunie mocy i potęgi!) or “Polish Capital welcomes you, our Advocate!” (Stolica Polski wita Cię, Orędowniku nasz!). And two months earlier, during the November manifestation, banners were carried with writings like “Let’s connect!” (Łączmy się!), “Long live America!” (“Niech żyje Ameryka!), “Long live Wilson!” (Niech żyje Wilson!), “Long live Polish Armed Forces!” (Niech żyje wojsko Polskie!). But the old press shows a completely different view. Chanting watchwords like “Long live Lenin and Trotsky!” (Niech żyje Lenin i Trocki!) or “Long live Soviet Russia!” (Niech żyje sowiecka Rosja!) in November 1918 provoked a brawl, what was commented by a newspaper: “If not for the help of Polish officers and soldiers, the provocateur would be ripped up alive”. Even a hundred years after these events, while reading the press reports, one can feel the unusual emotions of Poles, preserved in those watchwords.

During the Polish People’s Republic, the government had the monopole over the watchwords – those were elaborate, full of ornaments and glorification towards the dignitaries, Eastern neighbour or great ideas like peace or competition. But while looking at the watchwords from this era, the ruthless reality can be observed, but also a kind of linguistic creativity of workers’ and social movements. It was when the watchword was cut down to a minimum, with the maximal number of postulates and terror of the situation: “Bread” (Chleba), “Press lies” (Prasa kłamie), “Do away with the Muscovites” (Precz z Moskalami) or “Military to the barracks” (Wojsko do koszar).

Currently, when we have multiple sources of information, the watchword alone, to be effective, has to be more than an encouragement to action. It must be surprising, to provoke a reflection, to engage. This is why it more and more frequently refers to pop culture, is a wink towards the audience. It has a different function, because the media reality is different: in the past, the watchwords were one of the few communicates, whereas now they are in competition with hundreds of other messages. The Youth Strike for Climate watchwords accumulated different kinds of tools in themselves: graphic and sound wordplays, irony, polysemy, intertextuality.

At the same time, there are still some values, which, when violated, cause a lively reaction. An example of this would be a parody of the “God, Honour, Fatherland” watchword (every word was switched to a similar sounding one from a category of vegetables) that some politicians popularised, what caused a wave of disgust. This reaction shows that there is a group of watchwords essential for a particular community. They are deeply rooted in culture, tradition, national identity and any modification causes a reaction, usually negative, especially when significant values are being mocked.

And how does it look now, in the era of social media and popularity of memes? Did it also influence a shift in attitude towards watchwords and their function?

Yes, and I think it was absolutely visible in the watchwords from the women’s protests, but also in those of other social groups. Some graphic euphemisms appeared, like the eight asterisks, or illustrations that accompanied the watchwords. This coupling of words and images not only gave context but also had a mocking tone. For me, it was fascinating how inspirating were the full of absurd watchwords from public clashes between sport clubs’ fans, e.g. “[X] thinks, that in vitro is a pizzeria”, “[Y] thinks that Mazurek Dąbrowskiego (Polish anthem) is a cake” (in Polish, “Mazurek” is both a musical form and a type of cake), “[Z] makes tea using the water left after boiling dumplings”. These show that a modern watchword should not only encourage action, but also evoke emotions, create associations and surprise. This intensity can take different forms – vulgarity, pop culture references or intertextual games.

Your book ends on year 2020 – a time particularly intense in terms of political language, because of presidential elections and social protests. As a researcher and observer of public life, did you follow latter campaigns as well, especially the 2023 parliamentary elections and presidential campaign this year? Do you see a continuation, or maybe a change of quality, contents or form of watchwords and slogans, especially in the context of candidates’ speeches and public appearances, as they often use controversial, extreme or theatrical language?

Maybe, but it is a different case – there are a lot of these watchwords, so it is hard for me to give a clear-cut answer. As a receiver of these communicates, I have observed, that the same political symbols, that invoke common values, appear, such as fatherland, tradition, peace or freedom. That means everything, that Walery Pisarek once called positive banner words (miranda) – words, that have a clear positive character. No matter who makes the audience – people from the right, left or centre area of the political scene – these terms are positively received by everyone. And this is why politicians’ watchwords may come out as similar and unappealing. In this context, social watchwords stand out more, are unique, carry different values and are often more literal.

Indeed, it usually takes the form of candidate’s surname, for example for president, with the number of the year in which the campaign takes place. In your book you also mention the previous presidential campaign, in which Grzegorz Braun took part – his watchwords were similar to the current ones. Even during his introductions at the television debates, there always appeared the religious motif or whole phrases, that he repeated every time.

In this candidate’s case, it was visible previously, so we can talk about a continuation here.

During the reading of your book, I had an impression that it has a huge educational potential – not also during a rhetoric course on universities, but also in Polish, social studies or history classes in secondary schools. Thanks to connecting linguistic analysis with the historical and political context, your book can inspire young people to consciously take part in the public debate and critically view political communication.

For years, you have followed so many formulas and messages. Are there any that especially moved you, were particularly memorable or the opposite – made you laugh or surprised you with their form or effectiveness? In one word, do you have your “favourite” watchwords from the analysed periods?

Political and social watchwords are an uncommonly rewarding educational material. They show, how unchangeable is the nature of politics and social protests – similar values were fought for towards the end of the 1940s, in the 1980s, and now, when rises and better work conditions are being demanded. These motives are invariable. From these watchwords one can learn a lot of about history, but their huge didactical potential lays also in the fact that they help us learn how we are “bought”. There is even a book titled “The Power of Persuasion: How We’re Bought and Sold” by Robert Levine.

Advertising slogans exist to evoke the need of possession of a product or a service in us. Similarly, the political watchwords shape our view on the reality. For example, when we talk about a “good change”, it is not a neutral message – it carries a certain political goal and is a direct copy of what the politicians impose on us.

Similarly, in history, there are sets of words, that, when appearing together, influence the way in which we interpret the reality. This is why it is so important for young people to understand that the language used in public sphere is not accidental and the way, in which politicians talk to us, is meant to cause a certain effect. It is about making youth sensitive to phenomena like persuasion, manipulation or agitation, so they can differentiate between them and consciously receive the communicates. The awareness that someone wants to influence us and change our attitude, helps to interpret the surrounding reality better. Today, as we are flooded with different communicates from every side, it is hard to recognize true intentions and even differentiate between falsity from the truth. This is why this knowledge is so important.

In politics, is it even possible to talk about true intentions of the speaker? It is an issue to yet discuss. Nevertheless, it is worth sensitizing young people to the fact that the use of language in the public sphere is always intentional and often invokes the past. People, who target their communicates at us – especially the political ones – are perfectly prepared, both historically and theoretically. They learned techniques and mechanisms of influencing social behaviours; therefore, the use of suitable words and political symbols is not coincidental but has a certain aim.

And now, do you intend to continue analysing the political watchwords after 2020, or broaden your interests with other forms of political messaging, such as speeches, memes and internet comments? Or are you working on a completely new project, research material?

Currently, I am analysing a project connected with an IDUB grant – “A corpus of Polish political slogans and catchphrases (1918–2020)”. It will last until the end of 2025, so all the materials I collected for the book, will be published in a nationwide database, that will enable searching with the use of keywords. We are getting towards the end of the project, and I am planning on filing a request to the National Programme for the Development of Humanities, so the database can be expanded and a new one can be created, that will cover not only the watchwords from the periods that I covered, but also the more modern and older, as far as the research will allow.

My dream is also to create a European database of this kind, but for now it stays in the area of academic plans and aspirations.

We are getting closer to the next Lower Silesia Festival of Science (Dolnośląski Festiwal Nauki) in September. Can you reveal, what linguistic subjects did your team plan?

I have been tied with Lower Silesia Festival of Science for more than a decade now. It has begun during my studies, when I was working in a festival office as a part of my student practice. Memories of this time are lovely for me, because it was when I had an occasion to see from the backstage how a huge event, like a festival, is organized. Later, I came back there every year to take care of the promotional issues of the office’s activity.

When I was doing my doctoral studies and later, right after my defence, I organized different events by myself, I encouraged my students and the academic circle to organize projects, that created a lot of interest. We went to Ząbkowice Śląskie, where we organized a dictation, a contest of knowledge about modern Polish language, and various workshops, for example on advertising or spoken Polish language. All these events hold a special place in my memory; they were surely popular.

I kind of slowed down, when I started working on the book, but I am planning on going back to these activities. Regularly, every year, with a break during the pandemic, I take part in events organized by the Science Village (formerly: Knowledge Park), where we set up a Mobile Language Clinic every year. We have a set of riddles, quizzes and interesting facts there, which are addressed to all people, no matter their age, from young children interested with logopaedic exercises, through primary and secondary schools’ students, to adults and seniors. We try to prepare something interesting for each person, connected with Polish language, for example surname inflection, that always evoke a lot of feelings; feminatives and other issues that fascinate me academically and can be, at the same time, interesting for the audience. Therefore, I invite you to the Mobile Language Clinic. This year we will be there on the 13th of September.

Will the topic of politics be also present?

No, but our conversations with guests always lead to unexpected places. Sometimes we talk about the history of language, other times about the language of media, advertising, sometimes the topic of formal style is discussed. Sometimes the conversation also shifts to politics. We will see, how it turns out this time.

And the last question, linked to your book: do you have your favourite political watchword?

There is one that accompanied me when I was writing the book and it was my favourite back then – “No watchwords, only facts” (Żadnych haseł, tylko fakty). It shows that, in reality, we detach ourselves from the watchwords, we do not want to be associated with them, because they have the power to change the reality, so we claim just the facts. And at the same time, we express in in a form of a watchword. And this paradox is particularly interesting for me.

Translated by Gabriela Rutkowska (student of English Studies at the University of Wrocław) as part of the translation practice.

_____________________

We would like to remind you that next Thursday, on the 26th of June, at 6 p.m., a meeting with the author, dr Marta Śleziak will take place, as a part of the Z przypisami series (a collaboration with Wrocław Literature House). The author will present her book “Głosuj, broń wybieraj. Polskie hasła polityczne z lat 1918-2020” – an analysis of over 2000 political watchwords, that reflect social, cultural and linguistic changes in Poland.

Date of publication: 24.06.2025

Added by: M.K.