A few words about the Polonaise…

Another Polonaise for Fredro, a Wrocław event featuring high school graduates dancing at the writer’s monument in Wrocław’s Market Square, has just taken place.

The significance of the polonaise, not only for Polish culture, is highlighted by its recent inclusion in the UNESCO Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in December 2023.

We encourage you to read the article written by the staff of the Institute of Musicology at the University of Wrocław: prof. dr hab. Zbigniew Jerzy Przerembski, dr Agnieszka Drożdżewska and dr Grzegorz Joachimiak.

“I do not know of a dance,” says P. Guebriant, “that combines politeness, seriousness, and pleasure as much as the Polish one. It is a serious and chivalrous dance, the only one that supposedly befits the most dignified people: monarchs and knights. Its character has poise and national distinction, marked by solemnity. It does not express passion, but seems more like a triumphal procession…” (Łukasz Gołębiowski, Gry i zabawy różnych stanów w kraju całym, lub niektórych tylko prowincyach, Warsaw, 1831).

During the time of the First Republic, Polish “musical exports” gained great popularity in Western Europe, particularly in German-speaking areas. The two most important of these were the bagpipes (Europe’s oldest wind instrument) and the so-called mazurka rhythms. These rhythms are characterized by a specific arrangement of rhythmic values in triple meter, where shorter notes occur on the first beat of the measure, and longer notes on the second and third beats. Rhythms like these are common in various Polish dances, such as the oberek, kujawiak, mazur, and polonaise. The name “Polonaise” (from the French polonaise, meaning “Polish”) became standardized in the 18th century for this national dance. Historically, it has been referred to by various names depending on the social context and regional variations, such as “Polish dance,” “walked,” “rounded,” “polacca,” “slow,” “old-fashioned,” and “great.”

European Fashion for the Polonaise

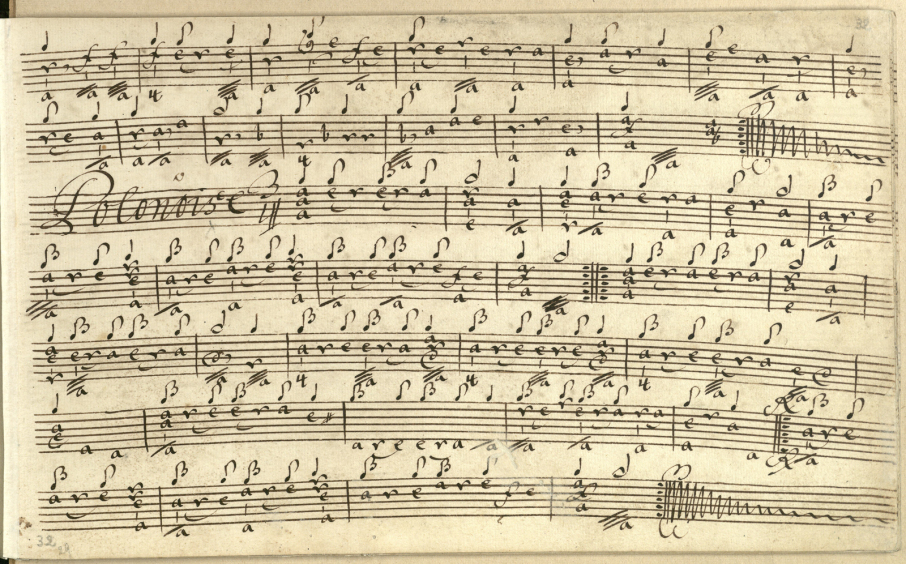

The origins of the polonaise are linked to various types of so-called polonics, preserved in manuscript and printed sources, as well as in keyboard and lute tablature notation, and in mensural and classical five-line notation. These were small-scale compositions with varied forms, meters, and melodic features until around 1730. The compositions that influenced the development of the polonaise were stylistically diverse, but all shared the common theme of “Polish” or “in the Polish style” in their titles, such as Chorea polonica, Polnischer Tantz, Balletto polacco, Taniec polski, and Polonoise. Similarly, works titled with specific references, like Ein Pollnischer Dantz pator (most likely referencing the Polish King Stefan Batory, as seen in Elias Nicolaus Ammerbach’s keyboard tablature from 1583, preserved in the University of Wrocław Library).

Recent research suggests that in 16th- and 17th-century compositions, the “Polish” characteristic was often conveyed through melody. After 1700, however, rhythmic features like those in mazurka rhythms became more prominent, signaling the early formation of polonaise rhythms. As a result, early compositions differ from later ones in key elements such as meter (even vs. odd), musical form (connections to foreign dances like pavans, galliards, courants, sarabands, and later minuets), and varied melodic structures.

The Polonaise in Ancient Silesia

Compositions exhibiting Polish style features can be found in Central European sources, including those from Silesia. Early examples include a collection by Bartholomäus and Paul Hessen, titled Etlicher gutter Teutscher vnd Polnischer Tentz, published in 1555 by Crispin Scharffenberg in Breslau. Another example is the organ tablature of Samuel Butschky, pastor at the Evangelical St. Christopher’s Church in Breslau, which includes a Dance of the Polish S.B.H., dated May 12, 1625. This manuscript is part of the “Wrocław collection” at the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz. Also in the same library is a Danzig manuscript from around 1640-1665, containing compositions by French lute masters, including several pieces titled Polsky Dance. French lute music also features the Polish Dance from the Wodzicki family lute tablature, dating from the last decade of the 17th century.

Traveling was a common part of the education for young people of noble birth, and musicians often traveled in search of work. One such musician, Daniel Speer (1636-1707), from Breslau, traveled across Europe and published Musicalisch Türckischer Eulen-Spiegel a 6 in 1688, which included a Pohlnisch ballet. In 1704, Georg Philipp Telemann (1681-1767), then an up-and-coming composer, became Kapellmeister to Count Erdmann II Promnitz in Zary. Telemann had the opportunity to study Polish folk music during his travels to Upper Silesia and Kraków, later incorporating Polish motifs into his works, including the Concerto alla Polonese and Polish Suite.

The Polish Style and its European Reception

By the 18th century, the Polish style was gaining popularity across Europe. Silvius Leopold Weiss (1687-1750), a famous lute player from Silesia, contributed significantly to this, incorporating stylized “Polonoise” rhythms into his compositions. In the early 18th century, a keyboard tablature from Silesia (held in the Jagiellonian Library) contains compositions linked to Polish style, including Polnischer Taniec and Taniec Poloni. Johann Sigismund Scholze (1705-1750) from Lubiatow near Legnica, under the pseudonym “Sperontes,” published a collection of dances in Singende Muse an der Pleisse (Leipzig, 1736), including polonaise-mazur rhythms.

The polonaise became a widespread form across Europe, especially in Silesian and Polish compositions. Notable examples include works by composers such as Georg Friedrich Händel (Concerto grosso, Op. 6 No. 3, part 4 “Polonaise”) and Johann Sebastian Bach (Orchestral Suite in B minor, part 5 “Polonaise” from Double, BWV 1067). These examples show the long and complex evolution of the dance’s characteristics.

Promenades for a Hundred Couples

The polonaise is an ancient dance, originating from the people, much like the Polish nobility, which grew out of the Slavic roots into a distinguished form. It is a majestic procession—a hundred couples walking gravely in a half-circle, reminding one of youth’s passing years. Those familiar with Polish history can appreciate the deeper meaning of the old polonaise. (Karol Czerniawski, O tańcach narodowych z poglądem historycznym i estetycznym, Warsaw, 1860).

Initially danced by both the people and the nobility, the polonaise gradually became a ceremonial dance at royal courts. It was danced in both triple and quadruple meters. The polonaise’s influence can still be seen in folk traditions, such as the Wielkopolska “chodzony.” Choreographically, it resembles the mazurka but is slower and more stately, without jumps. Traditionally, it is a rhythmic procession of couples following one another. The dance’s utilitarian role persisted until the Napoleonic era, after which its popularity waned as a social dance form. It regained favor in the 20th century, becoming an essential feature of formal ceremonies and balls.

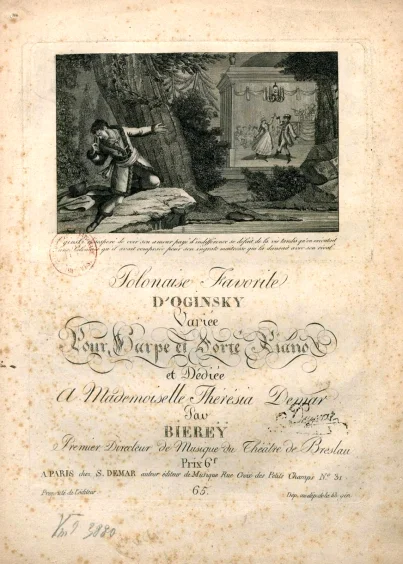

During the partitions of Poland, the polonaise took on a patriotic role, symbolizing the homeland. Although it was no longer commonly danced at balls, it was increasingly stylized by composers like Fryderyk Chopin and Stanisław Moniuszko. European composers also adopted polonaise rhythms, and these influenced opera music. Moniuszko’s The Haunted Manor features a polonaise in several scenes, including one marked by the famous clock chime. In Mickiewicz’s Pan Tadeusz, the polonaise became a symbol of national pride. Today, the polonaise by Wojciech Kilar, featured in the soundtrack of Andrzej Wajda’s 1999 film, marks the beginning of most celebrations, especially prom balls. In the past, such processions were led by Farewell to the Homeland, attributed to Michał Kleofas Ogiński (although its authorship is now debated).

In the 19th century, Polish polonaises made their way into the Wrocław theater community. Kapellmeister Gottlieb Benedict Bierey arranged one of Ogiński’s polonaises for harp and orchestra and published it in Paris. Similarly, Wrocław playwright Carl von Holtei introduced the famous Kościuszko Polonaise in his 1826 musical play The Old Chief, which became popular in theaters from Berlin to Lviv. Today, the Wrocław event Polonaise for Fredro continues the tradition of celebrating the polonaise with high school graduates leading a procession to the writer’s statue in Wrocław’s Market Square. This year marks its 24th edition! The inclusion of the polonaise in the UNESCO Representative List of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in December 2023 underscores its importance not only for Polish culture but for the world.