Photo: Alicja Wojtasz-Lubczyńska, edit. Dominika Hull-Bruska

A novel approach to the Iliad – is it even possible?

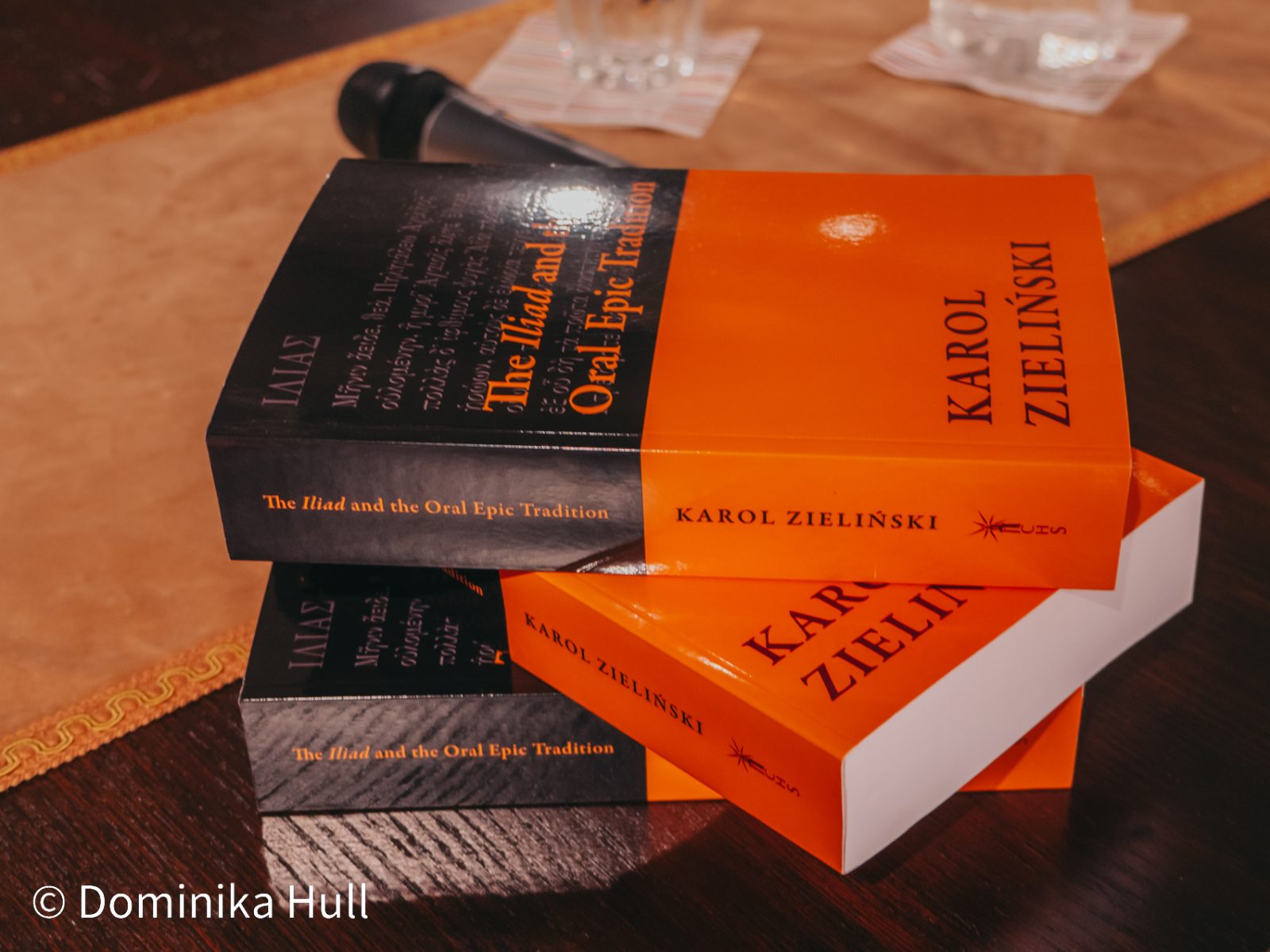

“Polish research into Homer has, for good reason, remained almost incidental over the past several decades. Taking on such monumental task as determining what Iliad truly was within an — ultimately lost — oral tradition required something close to reckless bravery,” admits a University of Wrocław scholar, Karol Zieliński, in a conversation about his passion and his new book published by Harvard University Press.

Katarzyna Górowicz-Maćkiewicz: “Your nomination was submitted by the Senate of the University of Wrocław for the Ministry of Science and Higher Education award. It seems safe to say that your recent book — ‘The Iliad and the Oral Epic Tradition,’ published by Harvard University Press in the renowned ‘Hellenic Studies’ series — played a key role in that decision. Would you say that having a Polish scholar’s work published by the press of the world’s top-ranked university (according to the Shanghai ranking) is a rare and remarkable event for Polish academia?”

Dr hab. Karol Zieliński, prof. at the University of Wrocław, head of the Centre for Interdisciplinary Research of Relations Between the Oral and Written Traditions, Department of Greek Philology, the Faculty of Languages, Literatures and Cultures:

It’s hard for me to speak on behalf of the entire Polish academic community, but when it comes to classical philology, the only case that I am aware of is a book by the late prof. Maria Dzielska from the Jagiellonian University about the life of Hypatia of Alexandria. It may well have inspired the production of the well-known film “Agora.” I hope I am not leaving anyone out. In the Hellenic Studies series, mine is undoubtedly the first publication by a scholar from a Polish university.

Photo: Alicja Wojtasz-Lubczyńska, edit. Dominika Hull-Bruska

What is the Hellenic Studies series?

It has been published since the early 21st century and is produced independently by the Center for Hellenic Studies, which is why Washington is listed as the place of publication. For several decades, the Center was directed by prof. Gregory Naga from Harvard University — a remarkable individual, one of the most prominent philologists of our time, and a leading expert on the oral roots of Greek culture. He has launched numerous academic initiatives, including the founding of this prestigious series.

My publication is number 99 in the series. For a scholar working on Homer and the oral tradition, there could hardly be a more fitting place to present my findings.

How did the publication of your book come around?

It became possible thanks to a grant from the National Program for the Development of Humanities (“Narodowy Program Rozwoju Humanistyki”) for the translation and publication. The deadline for submitting applications to truly reputable publishers was unreasonably strict; fortunately, it was later possible to change the publishing house, if a better one accepted the manuscript. I mention the translation because the book was initially published — under a slightly different title — by our University of Wrocław Press in 2014.

Is the new edition better?

It allowed me to introduce many changes. The new edition does seem better, because it presents the core arguments in a way that is much more clear and precise. In some matters, I went much further — drawing, for instance, on cognitive research. This allowed me, in a sense, to close the book’s concept in a concise research proposal.

Your book is quite extensive — 663 pages including the references — and covers multiple themes. What is it about?

It is indeed quite hefty, but then so is the research into Homer. When I found myself — thanks to the grant from the Lanckoroński Foundation — in the University of London Library over 20 years ago, and saw a wall of shelves labelled “Homer,” the very first thing I did was to try to estimate how long it would take me to read all of it…

So it would take…?

… at least forty years! Assuming that I would commit to it every single day! And that’s just books — not event counting the articles. And to think that I once considered our Institute’s bookshelf pretty substantial.

Photo: Alicja Wojtasz-Lubczyńska,

Edited by: Dominika Hull-Bruska

Every scholar makes selections in their research. That’s true, but this case was particularly problematic. Working on Homer is like a domino effect — tipping one tile inevitably sets off a chain reaction. The goals I had set for myself required me to delve into a vast array of issues within the Homerological studies. Of course, it is not simply about getting acquainted with other scholars’ points of views, but about setting new directions for research. That, in turn, necessitated acquiring comparative data from other cultural areas, oftentimes not taken into consideration in previous studies on the Homeric poems. In addition, it required utilizing the framework of other fields of study, such as anthropology, or the aforementioned cognitive science. Most importantly, as I dug deeper into this multilayered thicket of themes, I became increasingly aware of the need to rethink my approach to the Homeric issue from the ground up.

Photo: Alicja Wojtasz-Lubczyńska, edit. Dominika Hull-Bruska

Okay, but what is your book really about?

The starting point was the conflict between two distinct scholarly approaches — neoanalysis and oral theory — both established in the mid-20th century. Though not always perceived as opposing views, both schools address the issue of the original sources of Homer’s Iliad, or, its relationship to earlier epic tradition.

There are research-backed hypotheses by Milman Parry, concerned with oral tradition of South Slavs, that demonstrated the irrelevance of a certain issue that has been discussed for over 150 years — the so-called “Homeric Question.” According to Parry, the formulaic style utilized by Homer is engraved and shaped in tradition that did not use written language; hence, the poem is a product of many generations of singers, as well as the individual performer who would currently recite it. Neoanalysts, however, denied this age-old notion in the originality of the Iliad, claiming that it is secondary to traditions preserved in other — now mostly lost — epic poems about the Trojan War. Faced with the firm stance of oralists who widely disapproved of the idea that oral tradition can include imitation, an increasing number of scholars openly claimed that the allusive style and an incredible artistry or the Iliad must indicate the use of written forms.

My work pushes back against this trend. I attempted to depict that, not only was the artistic sophistication of the Iliad possible to emerge in oral tradition, but also that it is a hallmark of oral performance itself.

What is the most vital point in your interpretation on the issue?

I drew attention to a seemingly overlooked aspect of the creativity of the oral artist who, may be repeating a traditional song, but continuously adapts it to the specific circumstances of the performance.

So can we speak of an uncreative performer?

Creativity, understood as a striving for originality is a hallmark of the written culture. We were raised in it, so it feels natural to us. In the traditional oral tradition, however, a singer or storyteller conveying a traditional narrative does not indicate any sense of ownership. They wouldn’t even recognize the need to do so — which is why the grand epics of oral tradition, such as the Epic of Gilgamesh, Enuma Elish, Mahabharata, Iliad, or Beowulf, don’t have their “real” authors, but only mythical figures like Homer or Vyasa associated with them.

Consequently, such storytellers were considered as mere reproducers of traditional stories. Researchers following Parry’s findings which drew attention to the formulaic structure of an epic song, perceived the oral song-transmitting process as a solely mechanical operation. But where, then, is the space for creativity?

The problem lays in underestimating the connection between a performer and the circumstances of performance — and that’s where their artistic creativity truly comes to life.

Okay, so could you explain the relationship between the performance and its circumstances? It seems like you perceive a gap in Parry’s theory.

I believe I should indeed elaborate.

Oral theory rests on several foundational pillars. Its starting point lies in the aforementioned doctoral thesis by Milman Parry, which defined the concept of the formula — relatively short expressions that determine the specifics of a language in oral songs. In the academic year 1934–1935, Parry conducted ethnographic fieldwork in then-Yugoslavia, primarily in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Montenegro. His findings truly confirmed the validity of his earlier analysis of Homeric versifications. From the standpoint of classical philology, it was a truly unique kind of fieldwork — something that had previously seemed possible only with the help of a time machine. It’s almost a romantic tale, worthy of a Hollywood adaptation.

A young man arrives in Europe, from what was then the periphery of the academic world — from the University of California, Berkeley (I know how that sounds today) — or at the very least from the margins of classical philology. He proposes a novel and bold thesis that effectively bypasses the long-standing dispute between the “pluralists” and the “unitarians”. This young scholar was ready to bet everything on one card: he completed his doctorate at the Sorbonne, despite not speaking French when he first arrived in Paris. Then he organized an extraordinary expedition that arguably achieved more than all scholars before him combined.

Their findings demonstrate the remarkable power of youthful ambition: not only did Parry and his team earn the trust of the locals, but they also showed genuine curiosity about every aspect of the local tradition: the songs, the singers, their education, conditions of performance, the cultural diversity, and much more. They didn’t adopt a stiff or principled stance; instead, they approached their work with energy and enthusiasm that must have been palpable.

And let’s not forget the extreme conditions they faced: a remote, mountainous area, where Slavic languages — already notoriously difficult for Americans — had morphed into complex rural dialects. The language of the epic songs was on yet another level of linguistic challenge. The singers, caught in the momentum of their own performances, produced a rushing torrent of verses. Fortunately, Parry’s team had access to specialized equipment for voice capture, and were supported by a second assistant, a Croatian named Nikola Vujnović, whose role and importance in their endeavor cannot not be overstated.

Sadly, Milman Parry never had a chance to analyze the results of the findings of that research. Just six months after returning home, he died in mysterious circumstances — possibly an accident, possibly suicide, or perhaps even a jealous spouse’s act of violence. The work of this thirty-three-year-old brilliant scholar could easily have been lost or relegated to the margins of academic research. Fortunately, Parry’s young assistant, Albert Lord, who had accompanied him during the expedition, proved to be equally as brilliant a scholar in his own right.

It is trough Lord’s work that we have access to the findings of that research. One of his key insights was that the oral singer composes his song during the performance itself. This fundamental idea explained why various renditions of a single song — even by the same author — can differ from one another, to a greater or lesser extent, but sometimes quite spectacularly, with a performance’s length expanding several times over. Lord also observed the influence of performance conditions — such as listeners’ attention or engagement — on the overall “shape” of a song. To put it in simple terms: depending on the audience’s interest in a story, the singer can either make his performance shorter or longer.

What’s important is that this mechanism of variation wasn’t even considered in the mainstream discussions on Homer and, generally, the entire oral tradition.

Photo: Alicja Wojtasz-Lubczyńska, edit. Dominika Hull-Bruska

But why?

Recurring structures within the oral composition — such as the formula, but also the higher-order elements highlighted by Lord, like the typical scene or plot schematics — provided concrete material for the research (sic venia verbo). But how does one measure the changes in a composition, if every performance results in a different version? It’s pure chaos! What mattered to me, however, was to find and formulate the rules according to which those potential transformations occur — and then examine how such a process can be traced within the Iliad. In other words, what narrative techniques are employed by the authors(s) of this particular epic poem and what motivated them to arrive at such decisions.

So, how did the analysis go?

I came to the conclusion that the singer is constantly striving to capture the attention of their often non-stationary audience by using techniques specific to oral communication — techniques that, even if they occur in written literature, they either carry little importance or take on a different meaning. In my work, I delve into the details of how the performer shapes their story by interacting with the listeners, evoking emotions, and responding to their judgments and expectations.

The audience is an interactive part of the performance. It’s also significant that the listeners had likely already heard many other songs — some of which told the very same story of the Trojan War.

In what sense is the audience “active?”

In a theatre or a concert hall, the audience usually remains passive — focused solely on the reception of the narrative being presented, even though contemporary productions attempt to break this barrier between the performers and the viewers. The audience during an oral performance is the exact opposite, even though everyone enjoys hearing their favorite tales. Whether indoors or outdoors, people greet one another, chat, and sometimes even interact with the performer — asking for details or questioning the rationale or motives behind particular actions.

The audience also remains mobile: everyone is free to join in or leave the performance at any moment.

Someone might even tell the singer to stop — or, conversely, encourage them to continue. Every such interaction alters the shape of the story itself, directly or indirectly. The singer carefully observes their surroundings and can adapt their repertoire to ever-changing circumstances. Then, they might assume, for instance, that their listeners could understand a phrase in a certain way, or raise questions at key points in the story. Anticipating such behaviors can make interpretations about the presented plot or characters’ behavior. In a way, the singer plays a game with the audience, teasing their expectations or habits, and then satisfying those conventions, further engraving them within their culture. Sometimes it’s almost as if the performer discusses with themselves, directing questions to the air or to the Muse, whose authority they invoke. Their answer, then — and indeed the whole story — comes from the goddesses, with them as a mere tool through which she conveys words — so, it would be unreasonable to question the truth of what they deliver.

So, does a certain kind of tension arise between the singer and their audience?

Absolutely — and the singer constantly works to sustain and intensify that tension. These techniques differ vastly from those used by an author creating a literary text, which are typically based on Freytag’s Pyramid — a gradual buildup of tension leading to a climax, followed by a falling action and a coda-like resolution.

If we were to draw a graph, the oral epic convention would look more like a high-frequency sine wave — a continuous alteration between fear and relief in the audience. This means that the performer has to actively stimulate the attention of the listeners. At the same time, a listener can join the narrative at any given time — and still be drawn into its flow.

So, is there any difference?

A fundamental one. When holding a book, we can immediately estimate the length of the story — that alone often influences whether we decide to read it at all. When we decide to do so, we can stop at any point, reflect on a passage, and return to it later. We can go back to earlier paragraphs and refresh our recollection, or skip to the “interesting part” — if curiosity gets the better of us.

None of that is possible when listening to an oral performance. Only the performer can pause the narrative — say, if their throat gets dry — and the audience can only encourage them to continue if they’re eager to hear what happens next. Thus, we are seemingly locked into a linear reception of the story. But, that’s just an illusion: in reality, the singer possesses a wide array of tools and cues that guide the listeners on the narrative’s direction or its interpretation.

Can you provide an example?

From the standpoint of a reader, it would be counterintuitive to reveal what is to happen later in the story. To be left in the state of striving for answers is a kind of reader’s privilege, whose curiosity is gradually satisfied as the plot unfolds. What’s also relevant — which is also potentially overused in contemporary writing — is the element of surprise by an unexpected turn of events.

In the Iliad however, the narrative is filled with increasingly precise anticipations: for instance, Patroclus’ death can be easily predicted, as well as the circumstances or even who will commit it, long before he steps into battle. Similarly, Achilles’ death is also foretold, along with many other outcomes, such as the inevitable fall of Troy. Thus, the listeners are well-informed of what is to happen — but they don’t know when or in a certain sense, how.

What’s more, their expectations are constantly being manipulated: events unfold differently than anticipated, or are slowed down in every conceivable way… or simply don’t occur at all. In fact, the entire epic can be summarized as one prolonged postponement of the inevitable — the moment of Achilles’ death. Exactly those elements make up the interactive game played between the singer and their audience; the performer is well aware of the expectations, and they actively fan the flames of that anticipation.

It is really a mechanism of interaction.

That’s one of the key ways in which it differs from the reader’s reception of the story, but there are other characteristic features of the transmission of narrative in the performance. Largely overlooked was the fact that a reader is one, and a group is many people — and that difference determines both quality and the nature of the statements being conveyed.

The audience’s knowledge plays a crucial role here, as it stems from having listened to multiple performances of other songs, including those concerned with the Trojan War. A mental bond is created between the singer and the listeners, resulting not only from belonging to the same culture — as John Miles Foley described, seeing every compositional element as metonymically linked to every other implementation within that tradition — but also resulting from the shared engagement to certain mythical plots.

In other words, a given compositional element such as a hero arming for battle not only can be found across different characters in other different epics, but it is also peculiarly involved in a broader macro-narrative. One of such narrative is the Trojan War; only there does the formula “swift-footed Achillies” appear (a phrase that, interestingly, can be indicated by five different expressions in Greek), and only there does Achilles play the role of a “hero-protagonist.”

What I aimed to show is that the audience already knows the story of Achilles — especially the significance of his death in the macro-narrative of the Trojan War — and that the singer constantly evokes the memory of the circumstances surrounding that death. As a result, two simultaneous receptions of the story are created: the immediate episode of Achilles’ rage and the timeless story handed down through tradition. These “reminders” prompt the audience to fear for the fate of other characters — who, at any moment, can suffer the same fate as Achilles. The audience knows the fate well, because they heard it multiple times, perhaps in various other songs. Why? Because Achilles’ death is the pivotal point of the entire macro-story. And although it’s never shown directly, the most significant point in the traditional demigod’s fate — the tragedy of their inevitable fall — is still deeply felt. The listeners are emotionally invested in either his potential death, or the actual deaths of his symbolic stand-ins, most notably Diomedes’ and Patroclus’. Thus, the myth is closely intertwined with the logic of a sacrificial ritual — in which the substitution is an inseparable element

So is the Iliad just old content in new packaging?

An essential feature inherent in the style of oral compositions is modifying and reconfiguring the traditional motives — it’s always the same set of traditional elements, but presented in endlessly shifting configurations. Like a kaleidoscope. The author of the Iliad narrates an event, which may be considered new in some regards, i.e. conveying a narrative, which may not be present in other songs within the tradition; it is, however, the same at its very core; a timeless story, not altering the usual perception of the tradition.

When the author of the Iliad appears to be describing yet another episode about Achilles’ rage, in truth, the following events recreate the key scenes surrounding the hero’s death. It is a seemingly paradoxical situation — a different plot recreates the very same myth.

In the literary culture we were raised in, originality of a story is a priority. That’s why different narratives seem to us as completely separate stories. Such comprehension can be considered a limitation, — or, perhaps, a preference — shaped by literature, and one that is difficult for us to escape.

Although, in oral culture — as I’ve already mentioned — originality bears little significance, and yet people are always eager to hear new details of their favorite stories. Hence, multiversity of the oral tradition can lead to copying one same story into a new plot setting.

Does tradition, therefore, go hand in hand with innovation?

Absolutely. Recreating a myth in certain circumstances can fulfill a cultural need — which, in case of the oral culture, is also a religious need. In other words, in certain situations — especially during special celebrations or festivals bringing together an entire community, or potentially multiple ethnically-related communities — there arises the need to retell the myth of Achilles. But since this myth will be conveyed by several people competing with one another, each of them will attempt to give it a different, distinct shape. A shape not necessarily more aesthetically pleasing, but one that better engages the audience, and earns appreciation for the performer.

On one hand, this operates at the level of the form. Here, the discovery by Parry and Lord — that a singer tells a traditional story in his own way, which in effect favors those naturally skilled in storytelling — is fundamental. It might seem obvious now, but in earlier folklore studies, it was assumed that the best singer was the one who could most faithfully memorize and reproduce the traditional song without altering it. Such an assumption stemmed from the belief that oral performers merely conveyed treasures originating at the dawn of the nation — an idea directly related to the promotion of nationalistic values among Serbs, Russians, Finns, Irish, and others.

On the other hand, the ability to modify the story is revealed on the level of intent — an aspect I believe I am the first one to draw attention to. One could say that the “singer of tales” — as Albert Lord regarded the oral author — narrates his rendition in a way he understands it and the way he wants his audience to understand it.

Thus, recombination of traditional elements will be, from our point of view, an entirely new story — in reality however, it is a recreation of the very same, unchanging myth.

Does it mean that the Iliad is not innovative?

It may seem as a paradox — but the Iliad can actually be considered hugely innovative. In telling a story, one can indicate certain elements at the expense of others — and, above all, by highlighting praise for its heroes in a particular way, one can assign new meanings to the original narration. A hero’s behavior and their decisions are then reinterpreted.

The tradition, despite being perceived as conservative, is inherently dynamic. It only pretends to not evolve. It may appear as unchanging to a community of a given tradition, whose members cultivate it; however, the changing nature of a tradition is always noticeable from the perspective of an outsider.

It a much broader topic, so I will confine myself to one observation: since, in oral tradition, a thing exists only as long as it is remembered (as Walter Ong noted), any potential changes that occur are incorporated with belief that they have always been a part of it — and indeed, if those changes are retold, they truly do acquire such status.

And, if I understand correctly, Achilles plays a particularly significant role among the Trojan War heroes?

That’s correct. One essential thing was to establish what the Iliad truly was within the context of oral culture — and my answer is: yet another tale about Achilles.

The Trojan War itself was never the true subject of those stories. What was told was the extraordinary feat of the protagonist, as well as their consequences of his actions. There was a recurring theme: a hero salvaging his people from mortal danger performing a heroic act, but dying as a result. His death is the central point of the entire narrative. The retelling of this myth may thus be compared to a passion play — a ritual in which the death of Jesus is re-experienced with great pain and sorrow each time, just as intensely, even though Jesus’ worshippers are fully aware of his resurrection three days later.

In the traditional tale of Achilles, there is also something like posthumous immortalization, but this element doesn’t play a real role in the Iliad. Only the death of the hero is re-experienced. Thus, it’s no coincidence, then, that Patroklos’ death occurs precisely in the middle of the 25th day of the Iliad’s timeline. With Patroclus’ death, Achilles also dies — even if the death of this hero wasn’t explicitly shown in the narration. This formula has been present in religion for thousands of years — the only difference being that Jesus has no substitutes.

Epic song does not present events in chronological order — such a way of thinking, which shapes our historical comprehension, is a product of written culture. The events in the epic songs of the Trojan cycle were not, in my view, prequels or sequels of the Iliad; rather, they are always set at a single, fixed point in the story — shortly before the fall of Troy. At that moment, Achaeans face an obstacle that not only prevents them from the conquest of the city, but also threatens their very existence. Such challenge can only be overcome by a hero who would sacrifice himself for them. It is then, in the last year of the war, that all the key events unfold — or rather, one core event in particular, but presented in a multiplicated and diversified version.

And although the Iliad’s Achilles plays out his traditional role, he is pictured in an entirely untraditional way — as an intelligent human being, ready to defend the moral of his community, in which he had once been a merciful and compassionate warrior.

But everything changes when the community allows their defender to be dishonored. When the hero returns to battle, driven by grief over the loss of his friend, he resumes his role of the savior of Achaeans. And yet, in the end— despite having every reason not to — he shows mercy to Hector’s father, who has inflicted upon him the greatest of harms. The hero even shares a meal with his enemy — something that must have been a cultural shock for the original audience of Homer. That audience, however, is gradually prepared for this unusual event and fully notices the striking contrast between Achilles’ and Agamemnon’s behaviors at the beginning of the episode.

Agamemnon, unlike Achilles, humiliates — just as Priam was humiliated — an old father who brings the ransom and begs for the return of his daughter. Agamemnon outright rejects the plea — although he has no justification for his behavior apart from his egoistic drive to expand his power over the group. This act was so shocking and unprecedented for Homer and his audience, that it brought down a plague and divine wrath. By contrast, the hero’s actions restore the proper order. In the Iliad’s version of the story, however, it is no longer simply a matter of eliminating a monster, who is an outside danger for the Achaeans. Achilles does not step outside his traditional role, yet reveals an entirely different set of values.

Let’s return to the publication. Was it difficult to convince Harvard University Press to publish your book?

First and foremost, it was a huge risk. When I began researching the oral tradition of the Iliad in Poland, there was virtually no academic discourse on the topic; I hadn’t been taught it at university, and even now I often face misunderstanding when scrutinizing the topic of orality. Thus, I had to take matters into my own hand and carve out a path through a tangle of different conceptions and opinions. But that had its advantages — I was independent from the well-established notions. And, naturally, there was a risk of misunderstanding fundamental concepts at the very root of an issue. I worked alone for the most part, which is rather rare these days, and I submitted my work with great trepidation.

Fortunately, the response from the board that accepted your book was more than satisfactory?

That’s right. In one of the later conversations with prof. Leonard Muellner, who was among the reviewers, he said to me: “I’m not particularly interested in reading the things I already know — I’m more interested in what I don’t know.” I think that it’s the key to being published by prestigious (and especially American) publishers: the novelty of approach.

Polish research into Homer has, for good reason, remained almost incidental over the past several decades. Taking on such monumental task as determining what Iliad truly was within an — ultimately lost — oral tradition required something close to reckless bravery. I came to understand just how high their standards and expectations truly are during the editing work on my book, which also taught me a great deal.

Has your book already receive any feedback or reviews from the philological community?

The book was published in the autumn of 2023, but it has already been reviewed by prof. Ruth Scodel from the University of Massachusetts (known for her “sharp pen”) in the prestigious “Bryn Mawr Classical Review.” Among the many congratulatory messages I received — including one from David Elmer, head of Classical Studies at Harvard — there was a recurring remark: no one could recall Ruth Scondel ever writing a favorable review. It was most certainly an exaggeration and a joke, but if I could manage to convince — at least slightly — prof. Scodel to my ideas, especially given that I challenged her notions on several key issues in Homeric studies, I must admit, it would be deeply encouraging.

Her review includes the sentence: “every scholar of Homer should read this book” — and it’s hard to imagine a better recommendation. A nearly identical remark appears in the conclusion by a very respected French Homerist, prof. Françoise Letoublon (Prof. Emerita Université Grenoble Alpes). Her review was published in a European journal, Ágora, and it’s clear that she, too, finds much value in my ideas and the work I have done.

For the ministerial award application, I was able to include endorsements from prof. Gregory Nagy and prof. Leonard Mueller, but it stands to reason that I wait before others will incorporate my perspective in their own research — since citation frequency isn’t necessarily the best measure of value. In this regard, scholars in the humanities may need more patience than those in the hard sciences.

Do you intend to continue your research with similarly ambitious projects?

I have the honor of directing the Centre for Interdisciplinary Research of Relations Between the Oral and Written Traditions at The Faculty of Languages, Literatures and Cultures. Although we’re a small team, we consistently organize various different academic endeavors and popularize topics which are, in our view, unfairly neglected. After all, oral culture shaped humanity for roughly 19 out of the 20 millennia of our existence as a species. Yet, we have the tendency to only focus on what has shaped us in the modern time — and we value things accordingly.

This bias is evident in the persistence with which scholars try to argue that it was writing alone that made the Homeric poems great, or in the way contemporary expressions of oral culture — from folklore to rap — are often treated. The main element of this approach seems to be, among others, the journal “Quaestiones Oralitatis,” but you may also be interested in our current lecture series, which features leading international scholars working on oral culture and its interfaces. For various reasons, these speakers cannot attend in person, but the sessions are held live, with the speaker joining us virtually. I’d like to thank the Chair of Jewish Studies for generously providing a cozy prof. Jerzy Woronczak room, which made these events possible. In my opinion, engaging with an audience in a shared space is a completely different experience from attending an online conference.

In April, we hosted a prominent folklorist, prof Ronald James, and in early June, we will welcome prof. Gregory Nagy. I don’t hesitate to say that having the chance to listen to a live lecture of a true legend of philology — and engage in discussion with prof. Nagy — will certainly be a major event for every scholar and student alike.

As for my own plans — I have many, and some already are at advanced stage, but I‘d prefer not to speak about them just yet. It’s a topic I consider even more important, and, consequently, one that necessitates elaborate explanations. I was once told that this book was the work of my life — I disagreed, and I still hope that such a book lies ahead of me.

A few closing words?

If I may, I’d like to thank everyone who supported me — your kindness helped me overcome many obstacles — and especially my translator, Anna Rojkowska. To have a translator who critically and with such attention follows your thought process is truly a rare gift.

Thank you for the conversation!

No, thank you — for the conversation and for giving me a chance to draw readers’ attention to the subject of orality, and to Homer — long forgotten, overlooked, and definitely too frequently labelled as boring. My students know just how untruthful those opinions really are. In my view, the Iliad is the greatest poem in the history of world literature — and not only because of its literary qualities.

But don’t worry — I don’t go around telling my students that “Homer was a Great Poet,” full stop.

Translated by Arkadiusz Biały (student of English Studies at the University of Wrocław) as part of the translation practice.

Interview by Katarzyna Górowicz-Maćkiewicz, University of Wrocław

Date of publication: 20 May 2025. Added by: AWL