Beetles, oaks and bats – what links them?

How is a changing climate influencing the habits of bats? The latest research by dr Iwona Gottfried from the Faculty of Biological Sciences shows that these remarkably sensitive mammals are capable of adapting to new conditions with surprising speed, making use of unexpected hibernation sites. Published in a prestigious scientific journal, the study reveals previously unknown survival strategies and sheds new light on the ecological flexibility of Polish species.

Bats in temperate zones hibernate during periods when food availability is limited. They must select a resting site that provides suitable conditions to survive this critical time, when food (insects) is scarce. Choosing an appropriate shelter that allows them to lower their body temperature enables bats to reduce their metabolic rate and use around 80 times less energy per unit of time than if they were maintaining a constant body temperature. Under favourable conditions, bats can survive without food for four to five months.

Bats most commonly overwinter in caves, adits or cellars. However, progressive climate warming means that less insulated shelters – including tree cavities – are beginning to play an increasingly important role. Research conducted between 2017 and 2023 in south-western Poland has, for the first time, shown that tunnels gnawed in oaks by the larvae of the great capricorn beetle (Cerambyx cerdo), one of Europe’s largest beetles, serve as important winter refuges for several bat species. The larvae of this protected insect bore tunnels into the trunks of old oaks for several years, and these galleries can persist for decades. It turns out that these insect-created “microhabitats” are readily used by bats during hibernation.

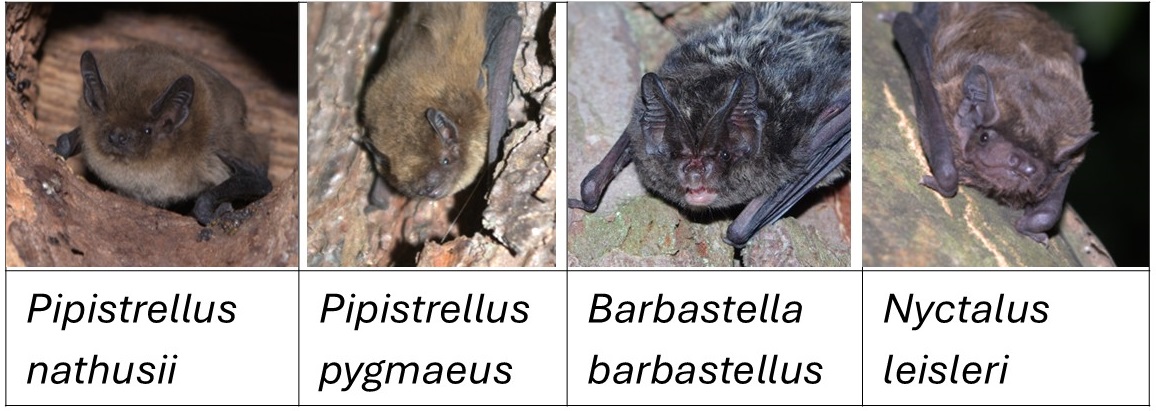

Bats were recorded in 46% of the monitored trees. In one oak containing capricorn beetle galleries, as many as 19 hibernating individuals were found. This suggests that the use of these larval tunnels by bats during winter is widespread. The research also showed that bats with different ecological strategies – both resident and migratory species – may use such shelters in winter. To date, hibernating individuals of three species have been recorded in larval galleries: Nathusius’ pipistrelle (Pipistrellus nathusii), soprano pipistrelle (Pipistrellus pygmaeus) and western barbastelle (Barbastella barbastellus). In the Mediterranean region of France, Leisler’s bat (Nyctalus leisleri) has also been observed in similar sites. As winter temperatures continue to rise – strongly influencing bat ecology – it is likely that more species capable of using this type of shelter will be recorded.

Higher winter temperatures, increasingly frequent due to climate change, allow bats to hibernate in shelters that were previously inaccessible because of the risk of freezing. Bats were most often recorded in galleries oriented towards warmer aspects (south and west) and at varying heights (0.6–15.5 m) above ground. The greater the number of beetle-bored tunnels, the more likely a tree was to become a winter “hostel” for bats. Moreover, during the coldest periods of hibernation, bats were recorded deeper inside the galleries, which may indicate behavioural thermoregulation in response to climatic conditions. The low mortality observed due to bird predation, and the overall low death rate (1.8%), suggest that beetle larval galleries provide a relatively safe and favourable environment for hibernation.

Both the beetles during their development and the bats seeking winter quarters selected old oaks with trunk circumferences of 240–600 cm. Such trees provide good insulation against low winter temperatures. As average winter temperatures rise, more trees may offer conditions conducive to bat hibernation. On the one hand, this is good news: the availability of natural refuges increases and bats may be able to shorten seasonal migration distances. On the other hand, in cities and managed forests, dead or dying trees are often removed, particularly those inhabited by insects such as the great capricorn beetle. This means that during increasingly short and mild winters resulting from climate warming, bats will more frequently hibernate in tree shelters that… regularly disappear. Tree felling is usually carried out after the end of the growing season, precisely when bats begin hibernation. Cutting down old trees containing capricorn beetle galleries without checking whether bats are overwintering in them may therefore lead to the animals’ deaths. For this reason, winter zoological inspections should become a mandatory element of tree maintenance and felling work.

Given that tree felling often takes place during the bat hibernation period, these findings highlight the urgent need to introduce woodland management principles that take nature conservation into account. Trees containing C. cerdo galleries should be removed only when absolutely necessary, and such actions must be supervised by specialists to prevent harm to protected and threatened species. Introducing legal provisions requiring zoological oversight would be an appropriate measure within active bat conservation, in response to the growing use of tree shelters by hibernating bats – a trend driven by rising winter temperatures in the context of climate change.

The research demonstrates how closely the fates of different groups of organisms are intertwined and how important old trees are in the landscape – not only in summer, but also in winter. Sometimes what appears dead and unnecessary turns out to be… essential for life.

The full article is available to read in open access.

Date of publication: 09.02.2026

Added by: EJK