Between memory and sound. On the craft of musical memory – an interview with dr Ryszard Lubieniecki

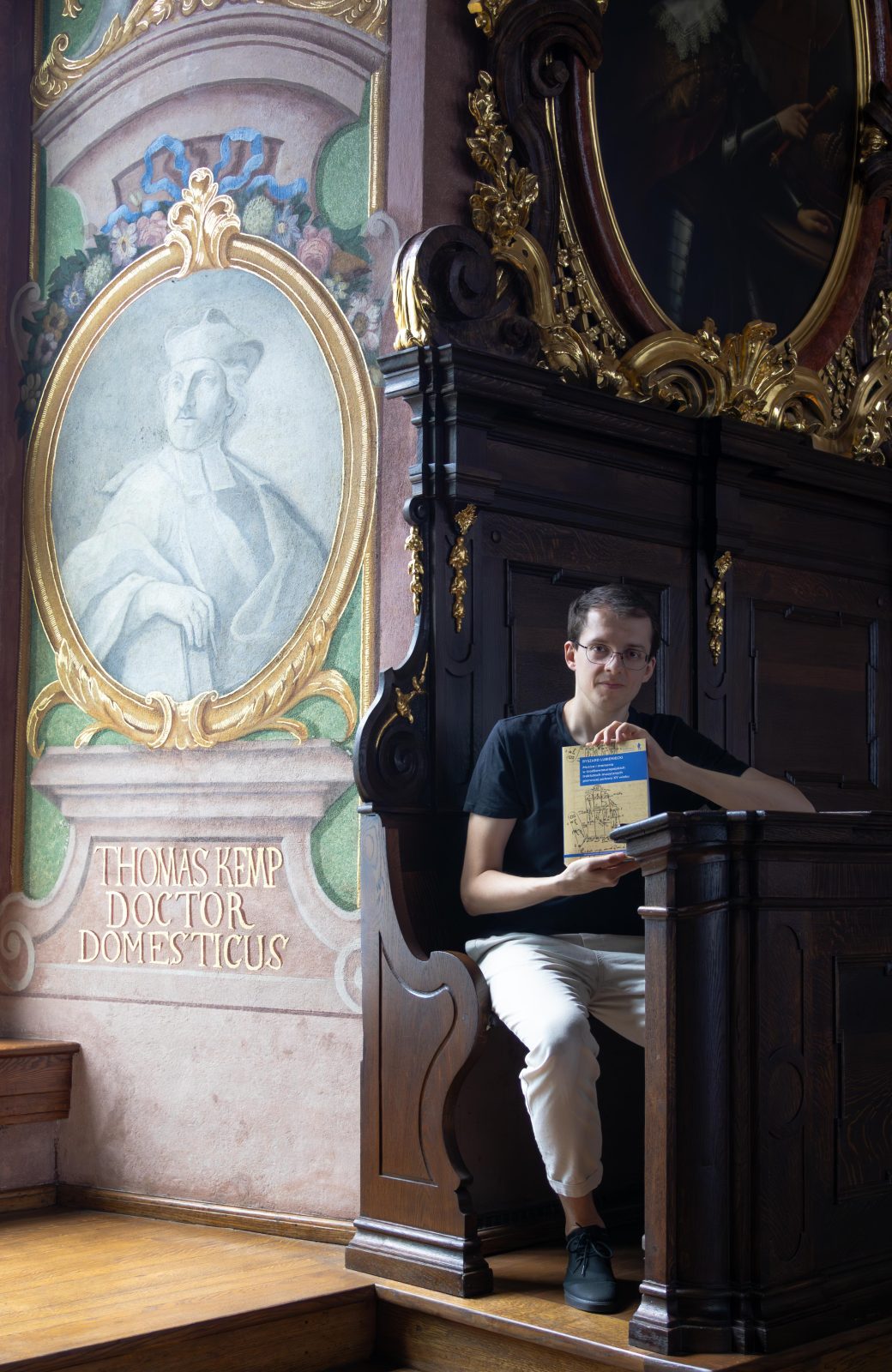

How did one manage to remember music before sheet music in its current form was invented? What was the Guidonian hand, and why is it still worth using in musical education? Is it possible to discern logic, emotions, or even elements of violence in medieval musical treatises? We are pleased to invite you to read Maria Kozan’s interview with dr Ryszard Lubieniecki – a musicologist, artist, and practitioner who not only examines music of earlier times, but also creates and shares it. This conversation takes as its starting point his latest book “Musica i memoria w środkowoeuropejskich traktatach muzycznych pierwszej połowy XV wieku”, published in 2025 by Wrocław University Press.

This is an interview about diagrams that were not only illustrations, but tools for thinking. About memory that was not an art reserved for the privileged, but a daily craft shared between student and master. About how early musical treatises continue to inspire both pedagogues and performers, revealing that knowledge from centuries ago can still be meaningful and deeply useful.

Maria Kozan: At the very beginning of our conversation, it is worth noting that the book “Musica i memoria w środkowoeuropejskich traktatach muzycznych pierwszej połowy XV wieku” grew out of your doctoral dissertation, marking an important milestone in the journey of a young researcher. Is the published version a faithful copy of the dissertation, or did you decide to expand, enrich, or rework it before publishing the book?

Ryszard Lubieniecki: In fact, the starting point for that book was my doctoral dissertation. The version that has been published is thoroughly revised and corrected – at least, I did my best, taking into account both the post-defense review of the dissertation and the subsequent editorial review by prof. Paweł Gancarczyk. In the meantime, I also further developed some threads from the dissertation, presenting them at conferences or publishing them as articles. Some of these elements were included in the book, so it can be considered an expanded version. The part devoted to diagrams was particularly extended. In fact, one of them, the Guidonian hand, is featured on the book’s cover.

Did featuring the famous Guidonian hand come as your deliberate choice? Were you the first person to propose such a solution, or was it a suggestion from the publisher? People who are into the music field immediately recognise the diagram – after all, the musical education of a young person interested in the rules of music starts with this hand. In other words, it starts with solmisation.

I proposed a few graphical elements sourced from treatises – most importantly, diagrams, which, as far as I am concerned, are one of the most important and most interesting aspects of this work. Frankly speaking, I believe that the chapters devoted to diagrams are among the strongest parts of the book. I felt most connected to the work while writing those chapters, and the process of analyzing the diagrams left the strongest impression on me.

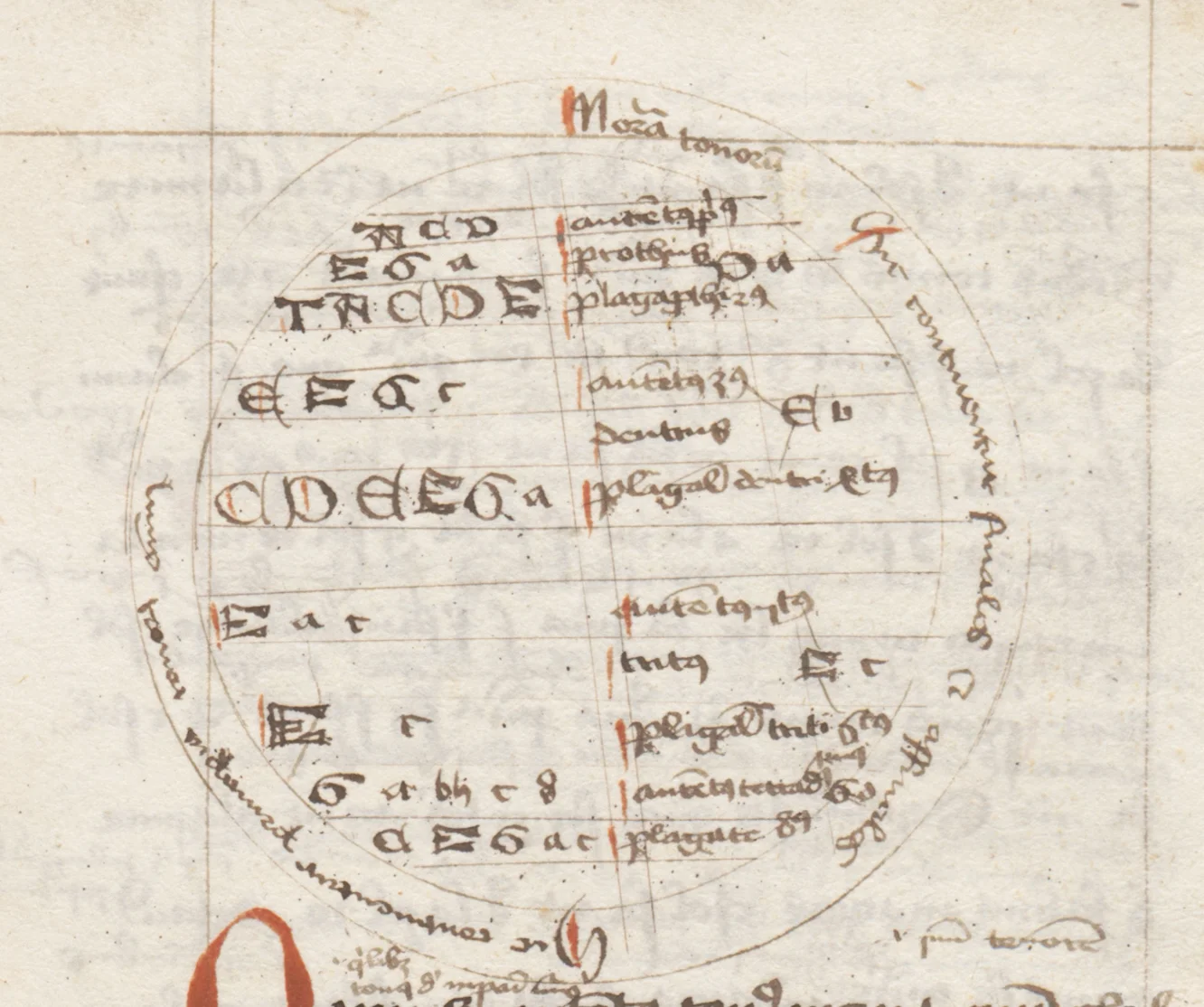

Among the proposals were diagrams taken from a manuscript kept in the Library of the University of Wrocław – the treatise “Opusculum monacordale”, a manuscript from the 15th century. Finally, the famous Guidonian hand was chosen, although I had some doubts. I knew that at least two other publications also feature the hand on their covers – although in different versions, likely taken from more visually striking manuscripts. I thought to myself: “Oh no, another book about memory and music – and the hand, again?” However, I did a small poll among friends. I sent them a few different versions of the cover design. Everyone, with one accord, said that it was the hand that caught their attention the most and worked best visually. So, the choice fell on it. Of course, the entire graphic design was done by the publisher, and I am also pleased that the back cover features another diagram – this one representing the musical system, the so-called“modi”, or in other words: a system of modal scales. That was a nice surprise from the publisher.

However, coming back to the hand on the front cover – what, in your opinion, might a layperson, someone outside the field of musicology, be able to see or interpret in this illustration?

If we look closer at the hand, it is possible to notice that it contains quite a few mistakes in the distribution of sounds. Inside, there are transverse lines that suggest the scribe – or rather the author of the copy, since we are probably dealing with a copy of the treatise – simply made a mistake. He placed elements in the wrong spots, and later tried to fix them by adding these lines. What interests me most here is the fact that the drawing featured on the book’s cover is not perfect or neatly done. It resembles a sketch, a note from the epoch. It also reflects the nature of the source material I analysed: imperfect, sometimes containing mistakes, but because of that – more intriguing and more relatable.

At first, it seems necessary to explain what the Guidonian hand actually is. In fact, the authorship attributed to Guido of Arezzo is quite conventional. In none of the existing manuscripts is there direct evidence that he created it, but traditionally this name is used. On the hand, sounds were marked with letters and solmisation syllables, which we now know as do, re, mi, fa, sol, la. Back then, they were ut, re, mi, fa, sol, la. The whole system starts from the thumb, and the following sounds are placed between the finger joints, forming something resembling a spiral that ends in the centre of the palm.

This tool was both a visual representation of the musical system and had a tactile function – student or master could literally indicate sounds on the hand. In this sense, the Guidonian hand was a mnemotechnic tool that helped to remember the sound system of the epoch. Along with this, it was also learned through the body – through gesture and touch.

Continuing the educational thread, can old mnemotechnics still be useful today when applied to modern methods of teaching music? To what extent can the knowledge of the “craft of memory” be helpful not only in the pedagogy of early music, but also in more contemporary educational contexts – even beyond the academic environment?

Along with Julieta González-Springer, with whom I run “Vox Imaginaria”, we had the chance to lead a workshop devoted to the Guidonian hand. Based on this experience, we can say with full confidence: it really works. We conducted these classes both in primary schools and in music schools. Of course, we focused mainly on the basic range, the first six sounds of the system. In other words, the basic hexachord. In one version of the workshop, the children prepared their own Guidonian hands by putting on gloves and marking the notes on them with markers. Later, when we pointed to the particular sounds on the hand, they were able to sing them clearly and without much effort.

We had similar experiences at the first-level music school in my hometown, Krosno Odrzańskie, where we conducted workshops with the choir. The teacher was surprised at how clearly and precisely the children were able to sing the sounds and intervallic leaps we pointed to, without any prior practice. It shows that this combination of treating sounds as physical points on the hand and adding the element of touch really works and has huge didactic potential.

In your book, you clearly outline the role of music theory treatises as didactic tools that support teaching through various mnemonic techniques. You have already mentioned the Guidonian hand, but there are other diagrams as well. Could you tell us more about their functions and purposes? What other types of visual representations appear in these treatises, and how did they assist in the process of learning music?

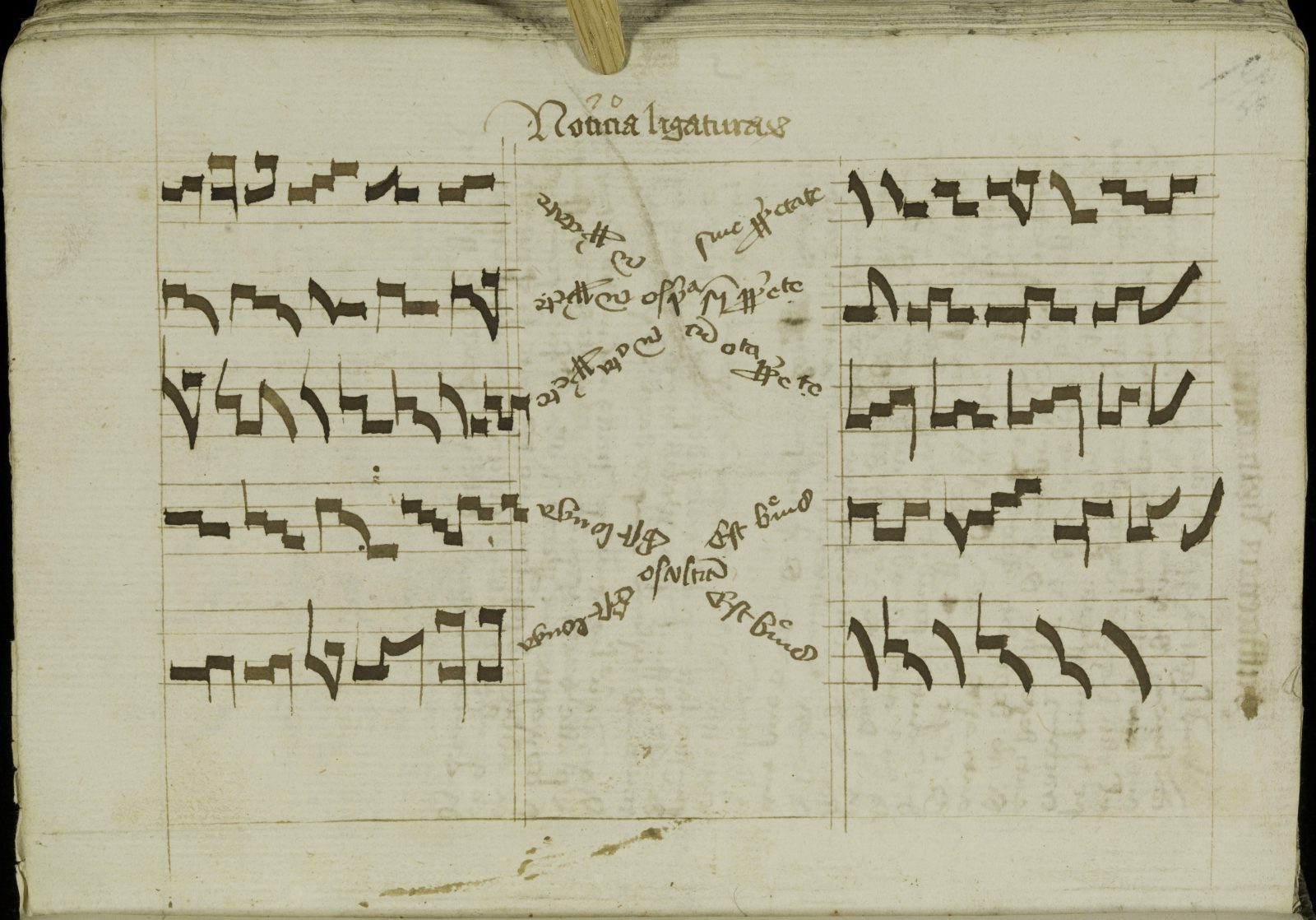

Maybe I will mention one of my favourite diagrams, Noticia ligaturarum, sourced from the first treatise in manuscript BOZ 61 from the National Library in Warsaw. It is an example that fascinates me in particular, though it requires a brief introduction to some details of medieval music theory. This diagram presents the so-called ligatures – connections of two or more sounds in mensural notation, which define rhythm quite precisely. Depending on how these signs are written, whether they go up, go down, or have “tails” (that is, additional lines), we interpret the rhythm differently: some of the sounds will be long (longa), others short (brevis).

What makes this diagram truly exceptional is the fact that it is based on the structure of the so-called logical square, known from logic and philosophy. The opposites are arranged along the diagonals, which in the musical version allows us to imagine rhythmic relations as interconnected oppositions. What is more, this is the only case I know of where the logical square (although in a simplified form) is used in music theory.

Often, when reading old notation, I think in terms of these logical oppositions. For example, if I have a ligature of two notes without tails in an ascending pattern, and I know these are two short sounds, then in an almost identical pattern, but with a tail on the second note, I can immediately read that it will be a long sound. This kind of diagram, then, serves not only as a visual aid but also as a full-fledged mnemonic tool that organises knowledge in a systemic and very logical way.

In which way did your experience as a musician-performer shape your book and influence the choice of research perspective?

The first draft of my doctoral dissertation focused mostly on instrumental music. As a performer on early keyboard instruments, my interest in this area grew naturally. I wanted to explore the instrumental repertoire of Central Europe. However, doubts quickly arose: are the existing sources sufficient to create a doctoral dissertation? There are few such materials, and most have already been described, which called into question the viability of the project.

However, as time went on, the project expanded and turned into a broader reflection, covering a wide panorama of treatises representing the key areas of late medieval music theory. In the end, instrumental music appears as the final topic discussed; and although it is the last chapter, it is quite a substantial one. But when writing about instrumentalists, I could not detach from the earlier theoretical issues, because the original question was: what did a historical instrumentalist need to know in order to play a given piece? Of course, it turned out that he did not have to know every detail of the theory as it has come down to us. Still, many of the concepts found in treatises on chant, mensural music, or counterpoint also appear within the framework of the art of keyboard playing – the so-called ars organisandi. So, in the end, I managed to get close to the original goal: to follow what an instrumentalist had to learn and how different theoretical threads come together in their practice.

I included my experience as a musician in the work as well. Earlier, I mentioned the workshops where we used the Guidonian hand. In the context of organ music, the concept of tactus struck me as particularly interesting. Tactus can be translated as “touch”. These were short musical formulas which, similarly to the sounds placed on the Guidonian hand, were meant to be absorbed physiologically, through the body. I think it is not a coincidence that the name refers to touch. Although the treatises do not state this directly, everything suggests that these formulas had to be “in the fingers” in order to use them freely in improvisation. In the book, I also described my own attempts to engage with this tradition. For example, I tested different variants of playing from memory in organ technique, where the chorale melody is placed in the lower voice in long rhythmic values, while free figurations are played above it. Of course, this is possible, but it quickly turned out that it is easier to improvise when the chorale is written out in front of you. Then, the memory is not so burdened, and you can focus more on the improvisation itself.

Interestingly, in sources from local centres, we find mentions of chorale books intended for organists’ use. Such a practice may therefore have been common: the organist had a written chorale, which served as a point of reference, and improvised above it.

I would like to ask about a source-related issue – meaning the access to the materials you worked with. In your book, different research approaches come together: musicology, memory anthropology, history, and also source hermeneutics. Focusing on the last one, what did your work with the sources actually look like? Did you mostly rely on digital resources, or did some of the materials require more international searching, working with originals in libraries or reading rooms?

In this work, I have not described any texts that were previously unknown to musicologists. Let me say right away that I am not a paleographer. I do not work on deciphering manuscripts from scratch. Many of the treatises that I analyse were created for semiprivate use and were often written in a rather sketchy manner, with numerous abbreviations that can be difficult to interpret without specialised training. To decode them properly, one really needs to be an expert in palaeography, and I do not count myself as one of them.

My work was based primarily on available editions of the Latin texts. In some cases, I also had access to modern-language translations (English or German). However, it was important for me to compare these editions with the manuscripts in digital form. In a few instances, I had to gain access to digitisations that were not publicly available. Besides that, most of the material was accessible online.

So, I do not work on sources that were unknown until now. The goal of my work was not discovering new texts, but rather the reinterpretation of well-known treatises in terms of medieval mnemotechnic tradition. The greatest challenge for me still lies in working with the Latin language. Anyway, I hope I have managed to develop in this area. The terminology concerning music in these texts is quite repetitive, which makes the work easier over time. Of course, threads that surprise me do appear; however, these are exceptions to the rule. And then, the authors of the editions help by explaining atypical fragments.

Would you like to say something about the Library of the University of Wrocław and the two treatises you describe in your book? What was your cooperation with the library like? Did you have an opportunity to use the sources exclusively?

One of the treatises – referred to by musicologists as the Wrocław Anonymous – is considered the oldest Central European text concerning mensural rhythm. It was not available in open access, but thanks to good cooperation with the University Library, I managed to obtain its scans quite quickly. For context: we are dealing here with the distinction between musica plana – that is, chorale without specified rhythm – and mensural music, where the rhythm is clearly defined and tied to rules concerning specific note shapes.

The second treatise is Opusculum monacordale, from which the hand placed on the cover of the book comes. In open access, only a microfilm was available, but I managed to obtain a high-quality, colour scan. That is important, because although the manuscript is not particularly striking, on the cover we can see red elements which are meaningful for mnemotechnique. According to Hugh of Saint Victor, one of the most important authors of medieval memory theory, the appearance of the book is crucial for remembering the material. That is why the presence of colours in this manuscript is of great importance.

You mentioned theoretical treatises multiple times, does it happen that you use them in performance practice? Or maybe there is one, particularly important to you, that you keep coming back to even beyond the work on the book?

It seems to me that all the treatises I worked on are present in my performance practice – though to different degrees. A special case is the treatise Opusculum monacordale; based on it, I composed an almost hour-long contemporary piece within the Wrocław artistic scholarship in 2023, performed as part of the Canti Spazializzati cycle. The piece combines early keyboard instruments, flutes, violins, and multichannel electronics – the audience was surrounded by speakers, from which they could hear, among other things, fragments read aloud from the treatise. That was a moment when I returned to Opusculum monacordale once again, but this time not as a researcher, but as a composer, as an artist. I also used diagrams from the treatise, interpreting them live as graphic scores, also involving electronics. That experience made this treatise especially close to me. [link]

How is your work at the Institute of Musicology connected to what you have examined? Among other things, you teach classes in counterpoint. Do the treatises you analysed in the book also serve as a didactic tool for you? How do you share their content with your students?

In one of the Warsaw manuscripts, there is a diagram that systematises the allowed intervals in counterpoint – that is the material I discuss with the students. I also refer to treatises concerning ars organisandi, in other words, playing on early keyboard instruments. The pieces based on the formulas described in them serve, for me, as a basis for improvisation and concert performance.

During the workshops on early music, e.g. ars nova, we were analyzing the logical square of ligatures together – students had an opportunity to practically use historical tools. It also happens that, when doubts arise concerning the mode of a piece, I reach for particular treatises to resolve them. In this sense, treatises are not a closed research subject for me, but rather a didactic and artistic tool in constant use. I think the book may serve as a kind of textbook for early music performers. I do not cover all the theoretical details presented in the treatises, but it might work well as a starting point for further exploration of these topics.

For a moment, let’s come back to the title of your book – Musica i memoria. How, in your opinion, does the knowledge of medieval musical thought, its categories and systems of thinking, impact the understanding of music from later epochs? Does this old theory resonate in modern musical practice?

An interest in medieval music theory can be absolutely essential for understanding later musical systems. Many of the terms we still use today have their roots precisely in that period. Terms such as “tone” and “semitone” trace back directly to the medieval concepts of tonus and semitonium. Our contemporary alphabetical pitch system also has medieval origins. The same goes for solmisation – today we use a simplified version, but its foundations reach far into the past. Even if not every student will focus on this era in detail, I see it as my responsibility to cultivate an awareness of this continuity, and of how old ideas continue to shape our current musical reality.

What exactly is memoria? How do you understand this term in the context of your book, and which authors or theoretical traditions do you refer to?

I believe that memoria is a topic that may interest not only individuals involved with music on a daily basis, but also a broader group of readers generally interested in the Middle Ages. In my work, especially in the first chapter, I analyze the most important texts concerning medieval memory. First and foremost, I base my research on the works of Mary Carruthers, which became a paradigm for me during the process. Her articles, books, and online lectures are always inspiring and allow me to take a new perspective on a given issue. Following her The Book of Memory, I introduce a distinction between ars memorativa (the art of memory) and the “craft of memory”, which I translate precisely as rzemiosło pamięci. Although I am still not entirely convinced that the Polish term is ideal, I wanted to clearly separate these two terms.

Importantly, most musicological works on memory refer to the “art of memory.” At first, I wanted to use this term myself in the book title, but the more I read, the more I realised that it is not exactly the art of memory in the sense assumed by the rhetorical system – a structured method of memorisation used by orators. This is the so-called “architectonic art of memory”, whose source lies in ancient rhetoric – a method based on imagining certain places, such as arches, houses, or rooms, in which we place images called imagines agentes. These are, so to speak, active, dynamic images that facilitate the process of remembering.

Yes, exactly, it is about “imaginary voice”, “imagined voice”. The name of our pop was created in a way that at the beginning we had “vox”, which means voice, proposed by Julieta, and later, I added yet another part which is closer to me; so, exactly imaginaria – imaginative thinking. Performing early music is, in some sense, creating perceptions about early music that are far from objective (even if they follow pieces of information from the sources).

Does the name of your group “Vox Imaginaria” come exactly from this concept?

Yes, exactly. It is about the “imagined voice,” the “imaginary voice”. The name came about like this: at first, we had just “Vox,” meaning voice, which Julieta suggested, and then I added the second part, which is closer to me – imaginaria, meaning imaginative thinking. Performing early music is, in a way, creating mental images of early music, which are far from objective (even if they follow pieces of information from the sources).

How exactly are imagines agentes understood in medieval treatises and what do they tell us about their role in the art of memory?

In medieval treatises, a lot of different imaginations appear, at times strikingly brutal, which are intended to help remember certain words or ideas. For example, in the fragment of Rhetorica ad Herennium concerning remembering a court speech, we imagine a situation where somebody was poisoned – a hospital room with a person lying on the bed. There is also an interesting wordplay related to the Latin word testis, which means “witness”. We imagine that next to the ill person there is someone else with a ram’s testicle hanging from the fourth finger of their left hand. That is exactly a mnemotechnical trick: testis means both “witness” and “testicle”. Ram’s testicles help with remembering that there were witnesses to this event. Harvey Caplan, the author of the substantial study and the treatise’s translation, also mentions that leather pouches were made from ram’s testicles, which might have symbolised the bribery of witnesses and helped remember the details of the legal case. This is a classic example of the “art of memory” – the most striking form of memoria.

Another example comes from Thomas Bradwardine, who proposed a gruesome depiction to help remember the zodiac signs. Aries kicks another Aries, resulting in a profuse haemorrhage. Virgo is cut all the way to the bust, and from her body emerge Gemini, who are attacked by Cancer, and so on. Both when preparing the speech and during its delivery, the speaker “wanders through” imagined places, seeing various images that remind him what to say. This is precisely the essence of the “art of memory” – a method based on imagination and the architecture of the mind.

However, in the theory of medieval music, the “art of memory” appears considerably less frequently. Using this term in the context of music is not entirely justified. Musical treatises are rather based on general principles of memoria. For instance, Hugh of Saint Victor, in a short introduction, describes a method of memorising psalms by dividing and ordering them in the mind in a particular way. In music theory, we have, for example, the alphabetical order of pitches or the solmisation system, both serving the practical purpose of remembering. Yet, they have nothing in common with the vivid imagery or architectural structuring of imagined places characteristic of the “art of memory?”.

You mentioned diagrams as one of the elements of memory formation and memorisation. Could you tell us how they were used in the Middle Ages?

Hugh of Saint Victor wrote that booksellers should learn how to use a single copy of a book in order to remember its structure. From our point of view, this may sound funny, but he advised learning all the psalms by heart, as he considered it absurd to constantly look them up in a book. For him, it was obvious that one had to be able to recite (or rather sing) any psalm, in any order. Today, we see it differently, which has to do with the matter of literacy and orality. Our approach to books is radically different from that of the medieval “manuscript culture”. Following Walter Ong, this culture combined literacy with orality. Although writing already existed and shaped modes of thinking, books were not widely available enough to be used in the way we use them today.

If we were in the Middle Ages, we know that access to books was limited. When we think of Gregorian chorale, what immediately comes to mind are scriptoria and monks who devoted their entire days to copying and producing manuscript duplicates. But how exactly did the process of creating, copying, and disseminating musical treatises look in the Middle Ages?

It depends on which period we are talking about. From around the 13th century, books became more accessible, partly due to changes in the technology of their production. At that time, more sketch-like and often semi-private manuscripts began to appear. They were not always large, richly decorated volumes made of expensive parchment, the production of which could require entire herds of cattle. The spread of paper significantly increased the availability of texts. Nevertheless, mnemotechnics continued to play a significant role.

Paradoxically, the greatest interest in the rhetorical art of memory in the Polish lands fell in the second half of the 15th century and the beginning of the 16th century, when these texts began to be printed. Despite technological progress, there emerged a greater need for tools supporting remembering and public speaking, especially in connection with the development of universities and the activities of preachers and clergy, who were more often required to speak in public. At that time, treatises were written that continued the ancient tradition of the Rhetorica ad Herennium. Earlier, this line was not that clear, which turned out to be one of the key discoveries while working on this topic. It became clear that the art of memory was not an unbroken tradition passed down from antiquity to the Middle Ages. In fact, it was “rediscovered” in the 13th century, with its significance emphasised in the commentaries of Albert the Great and Thomas Aquinas. Hugh of Saint Victor, who was writing about two hundred years earlier, represents an earlier approach to memoria, from before the renewed interest in ars memorativa. Therefore, it is worth nuancing this picture and distinguishing the art of memory from the more general resource of memory techniques.

What are you currently working on? Is there anything you did not include in the book but you plan to explore further in the future?

My interests expand across different fields, but when it comes to this work, although it is quite substantial, it contains a few threads that have not been fully explored and could be developed much further. At the moment, I am writing about them in the form of articles, which I hope will be published soon.

The most important element that does not appear vividly enough in the text is the transition from shaping individual memory, as described in treatises, to the actual use of these rules in didactics. In my work, it is only briefly mentioned that the treatises could also be performed – we do not treat them as textbooks or self-teaching manuals from which one could learn everything, but rather as aids to oral transmission and teaching. This, to my mind, explains some of the abbreviations and uncertainties found in some of them.

In chapter two, I also analyse the opposition between usus (practice, use) and ars (art). In chorale treatises, those who relied solely on practice without knowing theory were often criticised. One of the poems begins with the words Bestia non cantor – a wild beast, not a singer, is the one who sings only from practice, without knowing the art. Elsewhere, there is a comparison to a drunken man who does not remember how well he sang, in contrast to someone familiar with the art, who consciously controls every single step.

At the end of the treatise Opusculum de arte organica (“A Work on the Art of the Organ”), a reversed claim appears – the author says that usus (practice) outweighs ars (art). Although he presents his theory, he emphasises that what really matters is what happens in practice, meaning oral transmission, the master-student relationship, where the student imitates the master. It is very interesting; however, it is difficult to gain a precise insight into the course of this transmission.

Recently, you took part in the seminar “(Nie)pamięć i zapomnienie w muzyce” – the First Inter-Institutional Poznań-Wrocław Musicological Seminar Res Facta Nova. During the event, you delivered a speech titled “Punishing oblivion. On physical violence in music teaching in the context of the medieval mnemotechnical tradition”, which is quite in line with the thematic scope of your book. Is that precisely the direction of your current research?

Hugh of Saint Victor emphasises that when remembering material, we should also recall the circumstances in which we were learning it, as well as the teacher’s gestures and facial expressions. The vividness of the teacher played a huge role. Another author, Boncompagno da Signa, also touches upon this. When creating a list of mnemotechnical signs, he included beating of students during history lessons as a way of “hammering” knowledge into their memory.

We also have mentions from hagiographic accounts about choral situations, where children who dropped their gaze or giggled could get a slap with an open palm. It takes us back to the Guidonian hand – the idea that its sound would spread throughout the whole room. It worked both as a warning for them and a caution for everyone else.

These are further steps in expanding threads that appear in the book. The thread of music and violence is present there; however, I mainly base it on Bruce Holsinger’s work – the author of an extremely inspiring piece of literature, Music, Body, and Desire in Medieval Culture. In the book, I mainly refer to his findings while introducing a mnemotechnic theme based on my own analyses of the texts. However, it is only in the speech and article that I elaborate on this matter.

Taking the opportunity of the ongoing enrollment process at the University of Wrocław, I would like to raise the topic of digital musicology, which is gaining more and more importance and popularity. One year ago, at the Institute of Musicology of the University of Wrocław, the Digital Musicology Lab was created. Starting from the next academic year, the Institute will launch a pilot specialisation in digital musicology as part of its master’s degree program. Could you say something more about it?

Regarding digital musicology, I primarily deal with spectral analysis – that is, working with recordings and operating appropriate software that allows us to look into the “inside” of the sound in the form of visualization. The novelty in this field is, in my opinion, a more philological approach to musical notation. During classes, we introduce students to the basics of digital musicology. We also cooperate with Sonia Wronkowska from the National Library, who introduces software based on the Music Encoding Initiative (MEI) standard, which allows for the preparation of musical notation in a machine-readable data form.

Thanks to this, we can compare whole pieces, not just single elements like a few initial sounds or titles (as, for example, in the RISM database). For instance, if we introduce a new composition into the system, we can quickly see where and which fragments appear in other pieces written in the MEI standard. In this way, new technologies create a lot of opportunities for historical musicology.

In this context, we are collaborating with the Centre for Textual Genetics and Digital Transcription on the interdisciplinary project “Jak rozpracować XIX-wieczny sztambuch”, which combines literary and musicological competences, and to which students will be involved in the next semester. This is one of the important directions in the development of musicology. Our Institute definitely strives to be up to date with new trends.

Translated by Iga Grygiencza (student of English Studies at the University of Wrocław) as part of the translation practice.

Date of publication: 27.06.2025

Added by: M.K.