Collections that can hurt: On “sensitive heritage” in museums and university collections

The collection of a German researcher, Hermann Klaatsch, as a starting point for a discussion on the sensitive heritage at the University of Wrocław.

After the end of World War II in 1945, under the provisions of the Potsdam Conference, the western border of Poland was decided. The German city of Breslau and many surrounding areas were incorporated into Poland. As a result, the collections stored at, then, the University of Breslau [now: University of Wrocław] became the property of our country, including the collection brought from Australia by a German anthropologist — Hermann Klaatsch. The interest in the heritage he left behind and other anthropological objects is growing among both researchers and students.

We discussed the sensitive, and sometimes even controversial, heritage stored at the University of Wrocław with: dr hab. Renata Tańczuk, prof. UWr, dr Jacek Małczyński from the Laboratory of Contemporary Humanities at the Institute of Cultural Studies, dr Urszula Bończuk-Dawidziuk from the Museum of the University of Wrocław, and Michał Stefański, a student of cultural studies who is writing a master’s thesis on Klaatsch.

What is sensitive heritage?

Sensitive heritage is a category that has been used by museologists for several years. As dr hab. Renata Tańczuk explains, it was introduced by Philipp Schorch. It refers to heritage that is linked to a tragic past and the experience of trauma. It includes, objects acquired by force, often against the customary law of the community that is their rightful owner. For example, exhibits in museum collections that refer to a difficult past, e.g., related to the history of colonialism or World War II. Today, they pose ethical dilemmas related to both research and showcasing them in exhibitions. Examples of this type of heritage include human remains, photographs, sound recordings, ethnographic objects, e.g., religious or artistic, which were brought to European museums during the times of colonialism. They require special care and are particularly vulnerable, which can make them the target of attack or profanation, e.g., as a result of racist actions.

Hermann Klaatsch and his work

Hermann Klaatsch was a German anthropologist who became famous for his three-year expedition to Australia (1904-1907). During his journey, he studied the culture, art, and anatomy of the Aborigines. He also collected numerous ethnographic objects, which he sent to German museums. In 1907, he was appointed curator of the collections of the Anatomical Institute and the Ethnographic Museum at the University of Breslau for his research work. He held this position until his death in 1916.

The Department of Human Biology at the University of Wrocław houses, among other things, his collection of human remains, mainly Aborigine skulls, as well as a collection of several dozen photographs, mostly duplicates. The originals are kept in the Klaatsch family archive in Mannheim, where they are studied by a monographer of Klaatsch, prof. Corinna Erckenbrecht. Michał Stefański talks about the difficulties encountered in his studies on Klaatsch’s collection at the University of Wrocław:

— Klaatsch acquired skulls from various regions of Australia, often through questionable methods, e.g., by digging them out of graves without the consent of the families of the deceased. Human remains constitute most of what we consider “sensitive heritage,” as their acquisition and use often took place against the will and beliefs of the indigenous population. Another example of “sensitive heritage” can be photographs. The collection of the Department of Human Biology in Wrocław includes a series of photographs by Klaatsch. It is smaller than the one in Mannheim, but equally interesting. Some of the photographs were used in the educational process. To that end, they were transferred to glass slides, which were used to display the images during lectures and classes. The paper copies were probably showcased on the walls of the Institute of Anthropology or in the pre-war Ethnographic Museum. The photographs taken by Klaatsch are primarily anthropometric, but not exclusively. The subject matter of the collection is quite broad: some depict material culture, e.g., clothing; others show Aborigines during rituals, e.g., dancing or playing instruments; and some capture colonial violence: men chained, imprisoned, used for labour, such as repairing roads. In the early 20th century, these photographs were an object of anthropological research, often with a racial focus.

Troublesome collections

Working with sensitive heritage raises many questions. Should such collections be made available to the general public? How can we balance access to knowledge with showing respect? Do we even have the right to keep and make decisions about these collections? As dr Jacek Małczyński explains, provenance research is crucial in this context, as it helps us understand the environment in which the remains or objects originally functioned. When dealing with human remains, it is important to explore their significance to the indigenous community. For photographs, we must consider whether they were taken with the consent of the people they depict. In the case of ethnographic objects, such as items of worship, we need to ask what purpose they served and whether they were acquired by honest means. Provenance research presents a significant challenge, especially in the case of the University of Wrocław, where we are dealing with the history of an institution that has lost its continuity and whose collections have been parceled out. With incomplete documentation of the stored objects, understanding their history becomes all the more important.

When it comes to exhibiting collections, we are primarily bound by the law, particularly by the Museum and Monuments Act, which regulates the management and preservation of heritage. It applies to both “ordinary” monuments, i.e., cultural heritage, and sensitive objects located at the University of Wrocław. If an object is deemed sensitive and a decision is made to show it to the public, it should always be exhibited with an appropriate comment — adds dr Urszula Bończuk-Dawidziuk.

Repatriations

How can we work with sensitive heritage in a way that respects indigenous communities? There are several strategies, starting with placing objects in the proper context. Provenance research helps us uncover the history of many items in museum collections. Another important approach is to raise visitors’ awareness of the problematic nature of these collections. A group of student culture experts took on this task with regard to the ethnographic objects exhibited at the Museum of the University of Wrocław. As Michał Stefański says:

The current collection of the Museum of the University of Wrocław includes many ethnographic objects that were part of the pre-war university collections. The provenance of many of these objects remains unclear, as there are no surviving records or documents — likely destroyed during wartime operations. These objects come from various regions of the world, including Oceania, Australia, and Africa. The African collection contains items from former German colonies, specifically Namibia and Cameroon. As for these objects, we mostly have very basic information, such as place of origin, sometimes dating. Some of these objects are identified by belonging to a given researcher’s collection. Initially, these items were presented in a way that mirrored museum exhibitions from the 19th and early 20th centuries. Together with Aleksandra Podlejska, we aimed to highlight the historical context of their acquisition (colonial times), and how they were used. At the time, they served two main purposes: to study the customs of indigenous populations and to “preserve” the heritage of people thought to be on the verge of extinction due to the contact with Western civilization. Through this, we wanted to show that the way of presentation is not neutral, and these objects can be classified as “sensitive heritage.” To this end, we rearranged the display case, removed some of the objects, primarily weapons — often shown at exhibitions in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. We replaced them with objects related to everyday life, such as clothing and dishes.

People representing indigenous communities are also invited to take part in such activities. If these groups request the repatriation of human remains (In this context, we speak of “repatriation,” not “restitution,” in order to avoid objectifying human remains — emphasized dr Jacek Małczyński) or do not consent to conducting research using them, their opinion should be respected.

Sensitive heritage and plans for the future

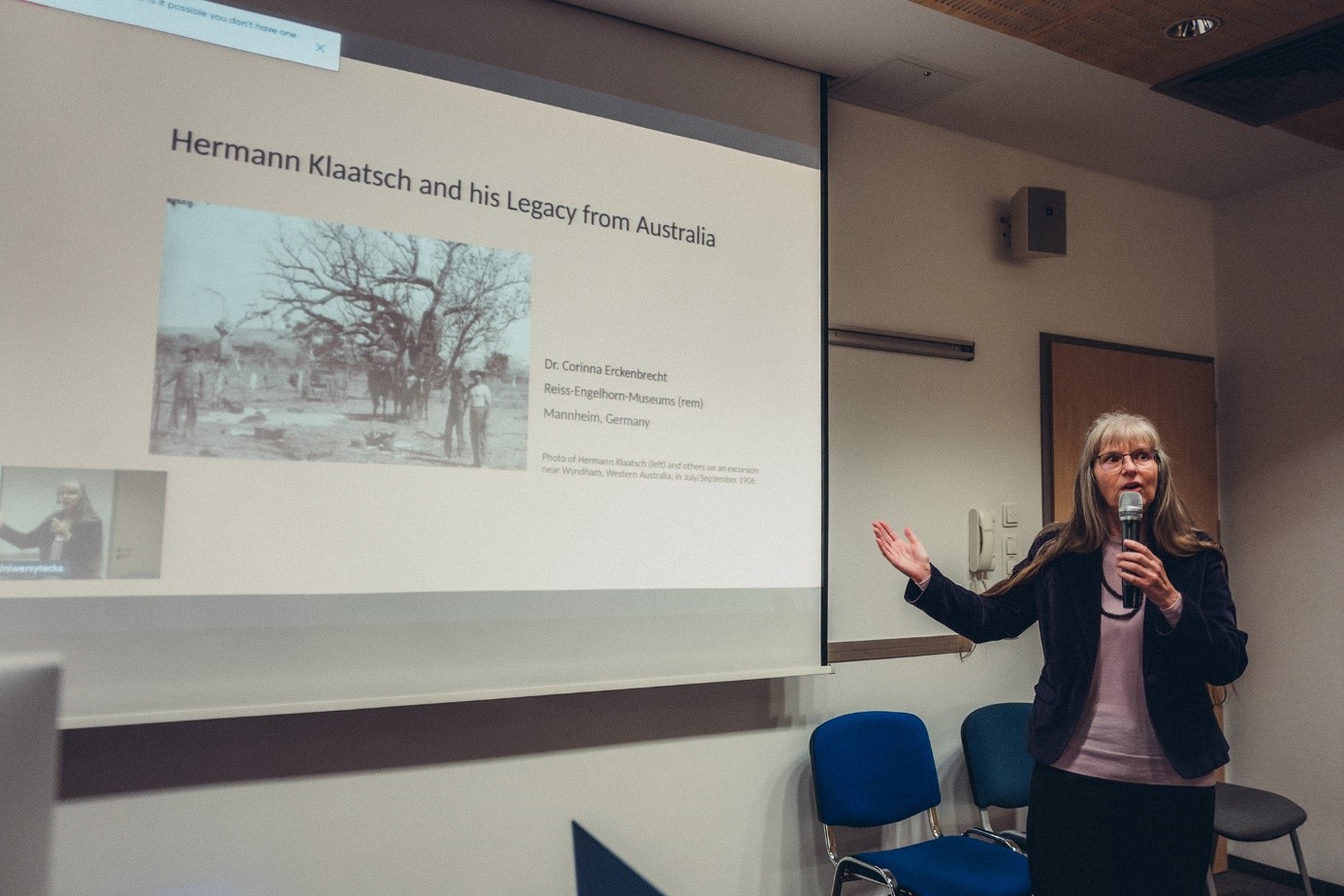

On November 14, 2024, an international conference entitled “Sensitive heritage in University Collections: Between Adaptation and Restitution” was held at the Library of the University of Wrocław. It was attended by researchers from Poland, Austria, and Germany, including prof. Corinna Erckenbrecht. The event was organized by the Institute of Cultural Studies in cooperation with the Urban Memory Foundation in Wrocław and the Centre for European Studies of Australian National University in Canberra. One of the reasons for organizing the conference was research on the Hermann Klaatsch collection. Currently, at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, at the request of the Australian government, which spoke on behalf of the indigenous communities of Australia, discussions are underway on the subject of repatriation of human remains. The conference organizers hope that the meeting will help develop good practices that will allow for the return of remains located at the University of Wrocław. It is worth mentioning that repatriation cases are already underway in several Western European museums, such as the Grassi Museum in Leipzig. In Poland, there are no strategies related to this process yet, so scientists are examining practices that have been implemented by other European museums.

The ethnographic collection, which is in the collections of the University of Wrocław, has so far been presented only partly. A significant part of the objects was transported to Warsaw after World War II and is currently located in the State Ethnographic Museum. The University of Wrocław has about 150 objects under its care. The reason for their display and conservation is an exhibition planned for May 2025. Its curators are dr Urszula Bończuk-Dawidziuk from the Museum of the University of Wrocław and Agata Stasińska from the National Museum in Wrocław. Students of the Institute of Cultural Studies of the University of Wrocław are also involved in organizing the exhibition. More information about the event will be available soon.

Anna Klementowska, Science Department, University of Wrocław.

This article is based on conversations with dr hab. Renata Tańczuk, prof. UWr, dr Jacek Małczyński, dr Urszula Bończuk-Dawidziuk, and an UWr student, Michał Stefański.

Translated by Weronika Kucharska (student of English Studies at the University of Wrocław) as part of the translation practice.

Data publikacji: 21.01.2025

Dodane przez: M.J.