Łemkowskie rozdroże – interview with prof. Jarosław Syrnyk

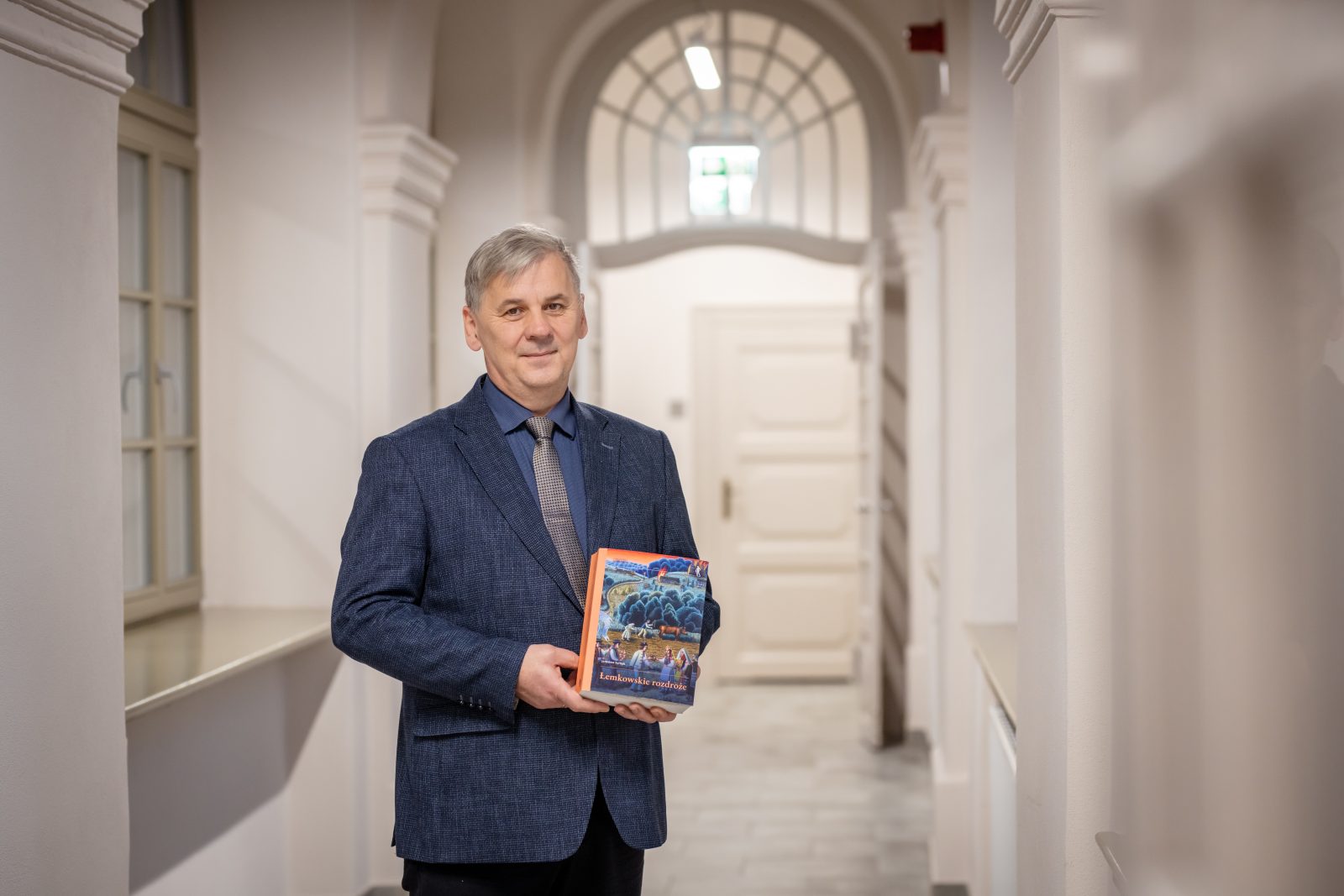

At the beginning of December, the University of Wrocław Press published a scholarly publication by prof. Jarosław Syrnyk, professor of history, employee of the Institute of Ethnology and Cultural Anthropology at the University of Wrocław and Rector’s representative for cooperation with Ukraine. The book entitled Łemkowskie Rozdroże (eng. Lemko Crossroads)is a continuation of the issues raised in two earlier monographs: Przemoc i chaos. Powiat sanocki i okolice w latach 1944-1947. Analiza anropologiczno-historyczna (ed. Institute of National Remembrance, Warsaw-Wrocław 2020) and Trójkąt bieszczadzki. Tysiąc dni i tysiąc nocy anarchii w powiecie leskim 1944-1947 (ed. Libra Pl, Rzeszów 2018). Lemko Crossroads focuses on the events of 1944-1947, as well as on later attempts to mythologise these events for the use of specific ideologies. We encourage you to read an interview between mgr Maria Kozan from the Department of Communication and prof. Jarosław Syrnyk.

Maria Kozan: The first point I would like to make is the cover of the book, which features a fragment of dr Dawid Zdobylak’s painting ‘On the Day of the End of the World’, was honoured at the 2nd Art Biennale in Tarnów this year. Was this a deliberate intervention? Was his work intended to show what Lemko villages, daily rituals and life were like before the war? A life that went on peacefully – grazing animals, marriages, cherishing traditions – before the war came and took everything away?

Prof. dr hab. Jarosław Syrnyk: As for the cover, it was not my idea. The University of Wrocław Press contacted the author of the painting, Mr Dawid Zdobylak, and out of the various proposals presented by the artist, this one seemed the most appropriate. On the one hand, it emphasises the various themes of the book, including the duality of the message you mentioned – life going on in a relatively normal rhythm and something that looms in the background, symbolising the moment of annihilation. This moment of annihilation of the Lemko Arcadia, the world before 1947, is the key context of the book’s content.

Although the idea for the cover was not mine, I found it visually appealing, relevant to the content and conveying the essence of the content. A big bow and thanks are therefore due to the artist for creating the image and to the publisher for the fruitful collaboration in its selection and use.

In addition to the cover, the title of the book – Lemko Crossroads – will surely attract the reader’s attention. I wonder about it because ‘crossroads’ makes me think of intersections or paths which today are often overgrown, forgotten and seem to lead nowhere. It makes me think of the Lemko villages of yesteryear, of which only a few crosses, small cemeteries or old apple trees remain – silent testimonies that once upon a time there were huts, churches, a vibrant life and a community living its rhythm.

The title is entirely original. In the introduction I try to explain how I arrived at the word ‘crossroads’ – I describe the train of thought that led me to it. Initially, I had a slightly different conception. It seemed to me that, in the context of my earlier books, the next one would simply focus on the annihilation of the Lemko Arcadia. However, in the course of writing and gathering material, a variety of themes emerged that I felt were relevant and worth including.

I wanted to show that the events of the Second World War and the post-war years have hindered the way we think about the Lemko Land. Contemporary attempts to reconstruct these events, including among Lemkos, are an important part of the story. It is a picture of a past that recedes with every day, week and year. It is not so much fading as taking on a mythological character.

For those who refer to this past, it is something important and precious. Everyone tries to extract from it those elements that are closest to them. These closest touches often concern the community in its most personal and narrow sense. It is about the memories of individuals, grandparents, great-grandparents and sometimes even parents who remember that period. People who were born in the Lemko Land and took their childhood memories with them. It is also about the memories of contemporaries about what their ancestors remembered. These memories have a specific character, mainly because childhood for most is a safe, friendly, almost fairytale time. They are less likely to return to difficult or painful events.

The second circle of memory is the environment associated with a particular village or parish. It is the memory of the community that existed in places such as Florynka, Bartne, Brunary, Wisłok or Komańcza. Their memories are part of a mythological story about that world – a bit of a ‘beyond the mountains, beyond the forests’ convention. Descendants, who gained their knowledge of Lemko villages from their parents or grandparents, often try to preserve it as intact as possible. They know where the buildings stood, who was next to whom, what the name of a stream or a mountain near the village was, or even what terms were used for the forest.

Within this circle of remembrance of the past, people and the community as a whole are also remembered – what group they formed, and how they communicated.

Up to this point, everything seems obvious, coherent and conflict-free. However, when threads related to politics and dramatic events, of which there was no shortage in the Lemko Land, as in other regions, appear in the memory, memories and, above all, interpretation of the past take on a different character. It is precisely such events that become another element that can guide the title ‘crossroads’.

A key period in the recent past of the Lemkos was the 1940s, particularly the deportations. On the one hand, to the Soviet Union – to areas from the Donbas, the steppe regions of Ukraine to the vicinity of Lviv, Ternopil or Stanislavov. On the other hand, Operation ‘Vistula’ carried out in 1947, resulted in the dispersion of Lemkos into the so-called Recovered Territories. As a result of this action, which lasted until 1951, the resettlers ended up in the provinces of Wrocław, Zielona Góra, and in smaller groups in Pomerania and Masuria. In this way, the material and physical paths of the Lemkos diverged, marking their fate with division and dispersion. It should also be added that in the 80 years that have passed since the Vistula operation, further significant changes have taken place. People migrated and left – often overseas – which further contributed to the dispersal of Lemko clusters. This alludes even more strongly to the idea of the ‘crossroads’.

Another aspect that underlines the significance of the title is ‘crossroads’ in the context of remembering the past. For some people, remembering the past means cultivating positive memories, often sanctified, almost sacred. Such memory is mythological and focuses on elements that are not subject to critical analysis.

On the other hand, there is also a memory that is more complex and sometimes controversial – some threads of the past are either particularly publicised or deliberately overlooked. This leads to the hypothesis that I try to verify in the book: that many aspects of the Lemko past, both within the community itself and in the wider social discourse, have not yet been fully worked through. There is a lack of confrontation and dialogue between the different visions of this history, which paradoxically only encourages the ‘battle for Lemko souls’. The Lemko issue does not have a single, simple denominator as it encompasses a variety of perspectives. It can be presented in a nutshell as a competition between two visions. On the one hand, Lemkoness is defined as independent and distinct, as defining a community that wants or believes it has already emerged as an ethnic or even national distinctiveness. On the other hand, however, there are, after all, Lemkos who consider themselves part of a wider Ukrainian group and see Lemko culture as an integral part of Ukrainian tradition.

At this interface, there is a conflict that concerns the interpretation of the past. It is about how we perceive our past, what we see in it, what we articulate and what we fail to notice or forget. There is a possibility that the clash of different points of view could lead to a correction and perhaps even to some consensus, if it had the chance to exist. The consensus we are talking about would consist of recognising that the past of any community is not homogeneous, and this applies to any group, whether we are talking about Poles, Germans, Ukrainians or any other community. The past cannot be homogeneous because it is a result of human nature. Secondly, in the discussion of the past, the right to different views should be respected, and this should not be a problem. Because the right problem arises when one view wants to dominate, preventing the articulation of alternative visions of the same past.

The book I have written describes in detail the situation related to the Lemkos and the Lemko Land but also tries to show the universality of their story. It should remind every reader that we are talking about a collective of people and that we humans learn from different examples and by observing the experiences of others. We participate in discussions that allow us to see different perspectives.

Before we move on to the main theme of resettlement, I would like to ask you to present the problem of ethnogenesis, with which you begin the first chapter of the book. As you note, there is a lack of source evidence that would unequivocally link modern Lemkos with any one particular tribe of ‘Proto Lemko People’, a group or nation that left their original settlements and settled in the Lemko Land. I also notice that I often meet Lemkos who identify with different identities – some consider themselves Rusyns, others Ukrainians, Poles or Lemkos of Polish origin (as shown in the National Census). I know that these differences have to do with a turbulent history and resettlement, which we will refer to in a moment.

So what are the findings regarding the origin of the Lemkos? What was the process of their settlement in the Lower Beskid and Sądecki Beskid? It is also worth emphasising that the folk culture of the Lemkos, of which you write, did not have political significance until the 19th century, which is also important in the context of their history.

Ethnogenesis or ethnogenesis? I ask myself this question because this issue can provoke discussion. We are used to science showing certain issues unambiguously, especially in the natural sciences or social sciences, where we often create typologies, definitions and precise classifications.

So before we go into details, it is worth establishing what exactly we are talking about. If we are talking about Lemko ethnicity or national or ethnic identity, we are dealing with categories that gained their right to exist in a specific discourse. We are talking about a discourse that spread only from the 19th century onwards. This discourse was initially limited to the literate, the intelligentsia, especially those connected with the Church, and therefore did not encompass the entire society that functioned at that time.

Rural local communities until the 18th/19th century can be imagined as communities that functioned primarily according to the rhythms of nature, linked to seasons, sowings, weddings, harvests, funerals, and sometimes to tragic events, floods, fires, assaults, which also happened. The topic of ethnicity tended not to occupy people, particularly in their daily lives. In the 19th century, a change began to take place in this respect, accompanied by changes in the way people thought about social structure. There were dynamic changes that led to the gradual participation of the lower classes in public life. This was linked to capitalist, modernist changes, to say the least. As a result of these changes, the model of the state and the concept of citizens’ subjectivity were redefined. After the Enlightenment, and especially after the French Revolution, the lower strata began to acquire subjectivity, which fitted in with the concept of the nation, redefining the very notion of the nation as a community.

Earlier, in the feudal system, the concept of nation was closely associated with a narrow layer of the nobility. As the system began to change, the concept of the nation began to evolve to include the peasant strata as well. Some kind of common idea or denominator had to become the key element to unite the nation in all its strata. Ethnogenesis was to explain this common denominator.

Closing the previous thread, let us now return to the question of ethnogenesis in the context of settlement processes in the Beskid Sądecki, Lower and part of the Bieszczady Mountains, where there was also a small Lemko headland. First of all, we have to conclude that we are dealing with different settlement waves (even limiting our view to the times starting from the late Middle Ages). Different groups wandered or were ‘relocated’ to the area and, given the low population density at the time, settled in different places, creating new clusters

This process took place in different ways, depending on whether we are talking about the areas that were part of the former Ruthenian Voivodship in the First Republic or those belonging to the Krakow Voivodship. This was later reflected in the formation of the Lemko question, in a specific form, although these are details. In any case, the settlement groups came into contact with each other, communicated with each other and overlapped, resulting in an overall effect in which one can see elements of Ruthenian, Wallachian and also West Slavic culture, i.e. Polish or Slovak culture. All this has been recorded, for example, in the languages used by the Lemkos, e.g. in geographical names, the accent, which in Lemko is fixed, unlike in other dialects of Ruthenian or Ukrainian (here, of course, if we were to agree with Professor Mikhail Lesiow’s classification).

Settlement and cultural processes were quite ordinary up to the 18th century. There was no political dimension or ideological component (at least in today’s terms) – it was not about the formation of a specific culture as it is sometimes described. Cultural layers overlapped and came into contact with each other. Added to this was the religious element. The people who formed this culture belonged to the Church of the East, which means that they attended liturgies held not in Latin, but in Old Church Slavonic. This introduces a noticeable difference between the settlements associated with the Eastern Church and those belonging to the Roman Catholic Church. Another important point worth noting is that the Przemyśl diocese of the Orthodox Church did not accept union with Rome until the end of the 17th century. Even later, liturgy in this Church was still held in the Old Church Slavonic language. These examples show that for a while, there were fluctuations, overlapping settlement layers, and diverse cultural and religious changes. Ethnic processes matured slowly, which is why, when I begin the main part of the book, I find that it is difficult to speak of any single tribe that could be called the ancestors of the Lemkos. We would then have to leave out a whole category of elements that contributed to the formation of the Lemko ethnos. This is, in simple terms, my approach and explanation of this issue.

This approach is a kind of opposite to the ‘obligatory’ search for ancestry that we are used to – whether in a family, historical or religious context. We are used to showing our identity through links to specific ancestors, to specific roots. In contrast, here we are dealing with a process that has a broader meaning that is difficult to capture within individual or family narratives. When we try to look at it in this way, we begin to encounter difficulties, because it starts to not fit into a generally accepted vision or becomes the subject of disputes in which we do not want to participate.

To summarise: one point of view may accentuate the Ruthenian component and say that the Lemkos are Ruthenians or Ukrainians, as we would call them today, while another may emphasise the Wallachian influence and claim otherwise. This is how this contemporary political and ideological discussion begins. My focus tends to be on trying, as a historian of recent times, to understand the context of the events that followed, rather than getting into details that may not be relevant in this case.

Moving on to the topic of resettlement in the 20th century, often when discussing Lemko history and culture, especially when talking to a wider audience, the dominant theme is Operation ‘Vistula’ and the deportation of the Lemko minority. However, before 1947, other, equally important resettlements had a huge impact on this community. I would like to ask you about these earlier events. I am talking about the deportations of Lemkos deep into the Soviet Union, but also about the exterminations of Jews and Roma, which you also mention in the book. In addition, as early as the 19th century, Lemkos began to leave their native lands, emigrating to the United States in search of a better life. Could you draw a broader picture of these migrations, showing how the various waves of resettlement affected the Lemko community?

It can be said that the migrations that took place until 1944 were relatively natural. People were looking for a better life and decided to leave, often under the influence of people who persuaded them to emigrate and at the same time profited from it. It is worth adding that we are not only talking about emigration from the Lemko Land. This phenomenon is well described, for example, in Martin Pollak’s book The Emperor of America, which presents this practice in an accessible way. People left, some returned, and those who stayed brought with them a new outlook on the world, going beyond the local reality, and seeing that the world could look different.

It is also worth mentioning that those who were looking for a place of education were also leaving. The children of Greek Catholic priests are a case in point. They were sent to study in larger cities such as Krakow or Lviv, where they studied in the seminaries, among other places. Those who had the opportunity to travel or come into contact with other people gained a broader view of the world. Through such encounters, these people had the chance to get to know other cultures, hear new languages and learn other ways of thinking. This certainly had an impact on the formation of their worldview. At that time (it is about the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century), they did not yet identify themselves as Lemkos but rather referred to themselves as Ruthenians.

However, already in 1940, as a result of an agreement between Germany and the Soviet Union, there was a departure of several thousand Lemkos from the Lemko Region to the Soviet Union. This was a deliberate action, although it cannot be described as a classic displacement. The departure in 1940 was voluntary. Soviet agitators visited villages in the General Government, encouraging the inhabitants to leave their homes and farms. Those who left soon found out what a country the USSR was and what conditions were like there. Some of these people managed to return, some immediately, others only after the outbreak of war when the Germans attacked the USSR. Then many returned, bringing with them news of the reality of the USSR.

Until 1944, these events had little impact on the functioning of the Lemko community as a whole. However, in 1944, the situation changed as the authorities of communist Poland and the USSR reached an agreement on a so-called population exchange between the Soviet Union and the People of Poland. The process of population exchange, including the resettlement of Ukrainians (including Lemkos), was initially to take place on a voluntary basis. Formally, there was to be no coercion. Nevertheless, the pressure to leave emerged relatively early. Some people, for example, those who had lost their farms as a result of war damage, left voluntarily.

Over time, however, it was noted that the scale of these, say, voluntary departures – both among the Lemkos and the rest of the Ukrainian population – was not sufficient. Beginning in 1945, physical coercion emerged, which became increasingly dramatic over time. The military became involved in the resettlement process, which further reinforced the coercive nature of these actions.

There were cases of pacification of civilians by the army in the Lemko Land. The two main cases of this type took place in the villages of Wisłok and Polany Surowiczne. Of course, the more famous one is Zawadka Morochowska, in which a total of about 80 people were killed, but this village is located in the Lemko borderland, so I do not include it in the events discussed here. This is simply because, for some researchers, Zawadka Morochowska is not the Lemko Land. In the case of Wisłok and Polany Surowiczne, the number of victims of the pacification was limited, a dozen or so people died.

In the western parts of the Lemko Land, such situations did not occur, but the authorities perceived that the inhabitants of these areas were also reluctant to change. Their stance towards resettlement was, moreover, variable – sometimes they wanted to leave, other times they did not. It depended on local events and dynamics in the community.

In summary, by 1946, around 70% of the Lemko population had been deported from Poland to the Soviet Union, which was the vast majority of this community. Those who remained – some 30,000 people – may have held out hope that they would be able to stay. Unfortunately, these hopes turned out to be in vain. In April 1947, the ‘Vistula’ Operation was launched, which displaced around 150,000 people from the areas where resettlement to the east had previously taken place. This included some 27,000 Lemkos, who were relocated to western and northern Poland.

The displacements completely changed the picture of the Lemko issue, because previously we were dealing with a compact settlement – neighbouring villages, settlements, and parishes that functioned in harmony with each other. After the displacement, we are talking about families scattered not only in western and northern Poland but also stretching from Donbas to the area around Zielona Góra. This is a huge space that cannot be ignored, and which, in my opinion, is often forgotten in the Lemko community, as well as among those affected by Operation Vistula. The scale of the depopulation is not limited to Operation ‘Vistula’. It was one of the many phases of depopulation of these lands – the removal of a total of around 620-650 thousand people from the areas of southern Podlasie, Chełmszczyzna, the so-called Nadsanie, or precisely the Lemko Land. The vast majority of Ukrainian inhabitants of these lands were deported to the Soviet Union, and some to the northern and western territories of Poland.

In 1956, as you recall, there was a change of political course when the Ministry of Agriculture allowed the return of displaced persons to the Lemko Land, provided that their farms were not occupied by other settlers. Although the topic of returns was raised, the process produced noticeable but at the same time limited results. How long did this period of returns last? Did the resettlers have a realistic chance of returning to their former homes? There have been stories of people making repeated attempts to return to their villages. Could you elaborate on these events?

This is quite an interesting case, as the returns started as early as 1947. It may sound surprising, but some daredevils decided to check what was happening to their farms after the displacement. However, if they were caught by the police or Security Office officers, they were sent to the Central Labour Camp in Jaworzno. This is how most such attempts ended. This was intended to instil fear and discourage return. One figure who, despite these difficulties, repeatedly returned was the well-known Lemko primitivist painter Nikifor. Although he was sent away, he returned again and again, until finally he was left alone and gained some fame in Krynica.

It may seem strange, but it turns out that single families and even small clusters of people who were not displaced remained in the Lemko Land. One example is the village of Komańcza, where even after returning from the Central Labour Camp in Jaworzno in 1948, Father Kaleniuk, pastor of the Greek Catholic parish, resumed holding services. This is one element that may seem surprising. Komańcza, associated with various events such as the presence of partisans, including the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA), in the nearby Chryszczata massif during the war, escaped full displacement. There were also villages in the Krosno district where it turned out that some people remained. Verification of these situations took place in the early 1950s. At that time, such villages in the Gorlice, Jasiel and Krosno districts were identified, where part of the Lemko population remained.

In 1951, the authorities carried out a statistical action to estimate the scale of returns. Based on the results of this action, in April 1952, the Central Committee of the Polish United Workers’ Party adopted a resolution aimed at stabilising the displaced population in the Western and Northern Territories. This resolution aimed to ensure that people did not return to their former lands. However, this meant that the process of settlement and imbibing of this population continued. To promote stabilisation, limited opportunities were introduced for these communities to function in the Recovered Territories, such as teaching children the Ukrainian language (the Lemko language was out of the question). Even Ukrainian language teaching points were created.

In 1955, the authorities concluded that the steps taken so far to stabilise the Ukrainian population in the Western Territories had not been successful. It was recognised that new measures were needed. On the one hand, this was accompanied by a ‘breath of new times’, we are talking about the period two years after Stalin’s death; on the other hand, the question of the management of the lands in south-eastern Poland was increasingly weighing down on those in power. These lands were not simple in the agricultural sense, they required specialist knowledge and a lot of work. The people who had been displaced from there had experience working on difficult mountainous terrain, and the new settlers did not necessarily know how to manage it – how the land had to be ploughed, how to cultivate it, how to care for it.

I am not an expert in this field, but I imagine that, despite various incentives from the state, the settlement process in the areas from which people were displaced as part of the Vistula action, and earlier to the Soviet Union, did not proceed satisfactorily. Today’s Bieszczady Mountains are a good example of this. Although it is not the Lemko Land, it is an excellent example of the difficulties encountered in the post-war reconstruction of areas where people once lived. When you compare the pre-war and post-war photos, you can see how much the landscape has changed. Significantly more forests have appeared in these areas, and the Bieszczady Mountains have been transformed into a national park.

This is an interesting fact that I once wrote about. The former Lesko district had a population of around 110-115,000 before the war. Nowadays, in the same area, comprising today’s Lesko and Bieszczady districts (ignoring the part that is now in Ukraine), the population is… Can you guess how many?

Half as much.

That’s exactly right. This illustrates how difficult it was to redevelop the area. There are now around 55,000 people living there, which is a significant decrease compared to the pre-war population. In the Lemko Region, the situation was somewhat different, but it would also be useful to consult statistics to assess the extent to which these lands were successfully re-settled and the extent of this process.

So it wasn’t just about ideological issues – whether to allow someone to settle or not. It was also crucial to manage the land so that it did not remain fallow but was cultivated. In 1956, new trends began to emerge: a change in thinking, a liberalisation of the political system and pressure from Ukrainians, including Lemko, circles. All this led to the authorities’ decision to close this chapter. Of course, displacement was presented as a necessity, primarily in the context of fighting the Ukrainian underground.

During the displacement, the principle of collective responsibility was applied, which, it was claimed, was conditioned by the realities of the time. Today, the approach to this issue has changed. Since 1956, the state has stopped interfering with the socio-cultural activities of the Ukrainian minority. For example, it was made possible to establish socio-cultural societies such as the Ukrainian Socio-Cultural Society, to publish their own newspapers such as Nasze Słowo (Our Word), or to organise cultural initiatives.

At the first congress of the Ukrainian Social and Cultural Society, when the desire to return to the former territory was expressed, the state agreed that those wishing to return could do so if their farm remained vacant. Between 1956 and 1959, the largest wave of returns took place, particularly in the Gorlice district. It is the descendants of these people who are now shaping the unique character of the region, which can be seen, for example, in the bilingual place names such as Gładyszów or Zdynia. It is worth noting that the dual naming is only valid where the requirements of the Law on National Minorities have been met, which requires an appropriate percentage of the minority community and its consent. Interestingly, not all those who have returned to the area have remained there permanently. Some of them chose to return to Lower Silesia or other places to which they had been displaced. These stories are extremely varied and often do not follow a simple, linear course.

Currently, the largest concentrations of Lemkos are found in Lower Silesia, Lubuskie Voivodeship and Lesser Poland Voivodeship, mainly in the Gorlice district. These communities are living testimony to a turbulent history of displacement and return, which continues to leave a mark on their identity and the culture of the regions in which they live.

How did the Lemko identity develop? I am referring here to Lemko society, in which, both in the past and in the present, we have, after all, examples of mixed marriages in which one of the partners is a Pole and the other a Lemko.

You know, it is the people who set the boundaries and then others start to believe in them. One generation passes, a second generation passes, a third generation passes, and these boundaries become more and more fixed in the consciousness. And finally, a generation comes along that says: ‘But someone wrote that this is the Lemko Land, someone wrote that this is Lemko. So I believe what he wrote’. And we are then back to the original question, but in a big circular motion. I believe him because he has written that this is the Lemko Land, he has done the research, and he has created this kind of ‘drawer’. The problem is that when these ‘drawers’ were created, positivism was going on, in which everything was supposed to be ordered, and systematised, as it had been before with Carl Linnaeus.

To this day we have a whole biological systematics in which we classify groups: group such, group such, government such, government such. From the 19th century onwards, everything had to be arranged and named in social terms as well. This is how cultural researchers, historians, ethnographers, 19th century song collectors and so on worked at the time. Based on these records, someone would say: ‘Aha, here is such a word, here is another word, so we take it into one district, and this word does not occur anymore, so they are no longer Lemkos’. And that’s what the whole mechanism was based on. This is how imagined communities were created, as Benedict Anderson says. And I would add that for all this there had to be, and must be, faith. A belief in what is being said and a belief that I am connected to a community, and if I believe that, I will justify it to myself in every way possible, defending myself against anyone telling me that it is not. It is mine, it is sacred.

Regrettably, all sorts of cultural conflicts are also based on this, because people approach it emotionally. You used the term ‘mixed marriage’, which is quite popular. But where does this lead? It leads to a situation where we start thinking in terms like: “I am half this, half that”. How can one be half this, half that? The individual is entirely himself. If we have respect for the individual as a person, then we can not talk about mixed marriages or any other divisions. We all come from different groups in one way or another. If we wanted to go that way, unfortunately, history has shown that it leads to racism.

Identity is a very broad concept. It is not limited to ethnic or national identity. Although we have always been aware of this, today we are beginning to put a different emphasis. The concept of identity is expanding, directing attention to the individual, to the human person. Of course, the fact that an individual is part of a collectivity is of great importance, but this does not change the fact that he or she does not cease to be important as a human being, as an individual. Often we still tend to classify, to segregate people, stuffing them into different ‘drawers’, and writing them into categories that correspond to our ideas of identity.

I have the impression that the topic of the resettlement of the Lemkos, thanks to new research and publications, is becoming closer to us Poles. In a sense, we are giving voice to those who experienced fear, stigma, injustice and loss of everything, who were deprived of the opportunity to return to their small homeland, their fatherland.

On Monday, 9 December, I had the opportunity to participate in an author meeting between Mr Jerzy Starzyński and prof. dr hab. Rościsław Żerelik at the Ossolineum, devoted to two volumes of the publication Preselyły nas musowo. Listy Łemków z lat 1947-1948, published by the Lemko Song and Dance Ensemble ‘Kyczera’ in Legnica. You also took part in the event, sharing memories of your friendship with Jerzy Starzyński and talking about the origins of your family, who also come from the Lemko Land.

My parents came from the Lesko area. My mother was born in Średnia Wieś and my father in Weremień. Both of these villages are located in the former, and also in the present Lesko County. In 1947, when the resettlements took place as part of the “Vistula” Operation, my parents did not yet know each other.

My mother’s family was relocated to Mirosławiec in what is now the West Pomeranian Voivodship, Wałcz County. My father’s family, on the other hand, was relocated to Łozice. There, my father lived with his parents and sisters in a part of a former German house that lacked a toilet and running water. Only the electricity had been supplied. Water had to be fetched from a well 500 metres away – something I still remember from my childhood.

My parents met at a family event – probably a wedding or a party. My father, travelled about 100 kilometres by motorbike to meet my mother. And that’s how their history together began.

Are these villages where my parents come from the Lemko Land… It depends on who you would like to listen to and what map you look at. For some, the area from Krynica to the San River is historical Lemko Land. If one accepts this definition, one could consider that my parents come from the Lemko Land.

However, other researchers point out that such boundaries of the Lemko Land were stretched too far to the east – in the area where my parents came from, there were supposed to be other cultural features, such as the way of speaking, architecture or traditions. For example, there is a map in the Folk Architecture Museum in Sanok, which shows that this area was inhabited by the so-called Dolinians, not even Boykos, let alone Lemkos.

My parents were displaced from there, and the language they used at home can be described as very local, strongly rooted in the cultural realities of the area. It was a unique way of expressing themselves, taken from their hometowns. When I compare the words that were used at home during my childhood and some Lemko words, they are very similar.

This event at the Ossolineum, as well as the contact with your book, made me reflect more deeply on the history of my own family. I am another generation that knows the events of the resettlement only from fragmentary stories, because in my home, or rather in the home of my mother and grandmother, discussions about what happened in Poland in the 1940s were avoided for a long time. I do know, however, that my ancestors were also displaced as part of Operation ‘Vistula’ to the Recovered Territories. Thanks to the determination of my mother, Bogumiła, who wanted to know the story of her Telech grandparents from the Maziar village of Łosie near Gorlice, and our contacts with many people, including Lemkos, I have been able to explore this topic for 25 years and observe the changes that have taken place.

In your book, I was particularly interested in the issues of the past and memory. It is not an easy read. The history of the Lemko Land, the history of Lemkos, is complicated, difficult and unfortunately sad.

This is true. This whole book shows that when we recreate the past, despite our efforts, it will not be an objective process. And this is something I spoke about at the meeting with Jurek Starzyński, although I did not express it explicitly. We are used to thinking about history in terms of objectivity, as Leopold von Ranke, for example, taught us. We think that history must be reconstructed objectively. However, after years of studying, and reading documents and books, I have concluded that this approach is not necessarily correct. Perhaps not so much that it is pointless, but it is more legitimate to acknowledge that we are writing what we understand from the traces of the past, rather than claiming that we are writing ‘how things really were’. When I report on how I understand the past, it does not mean that I want to impose my vision on others. I am saying ‘this is how I understood it, I have a right to it and this is what I think’. Of course, any speech is a form of persuasion – even what we don’t say influences the listener. But it is through conversation that we are human beings. No one should take away our right to express our opinion. I think that as long as we talk to each other, it will be fine.

Translated by Marcelina Kida (student of English Studies at the University of Wrocław) as part of the translation practice.

Date of publication: 18.12.2024

Added by: M.J.