Our scientists are analyzing the flood’s effects

Over a month has passed since the catastrophic flood which in September 2024 affected a huge area of Central and Eastern Europe. We followed its enormous social and economic effects in the media. About the difficult job of our scientists in the flooded areas, about their emotions and dilemmas talks dr inż. Matylda Witek, assistant professor in the Department of Geoinformatics and Cartography, head of the Laboratory of Unmanned Aerial Earth Observation.

The rise of water levels resulted from the Genoa low bringing a cloudburst which continued for a few days. In some places, within one day, close to 300 mm of rain fell, which constitutes an average for half a year.

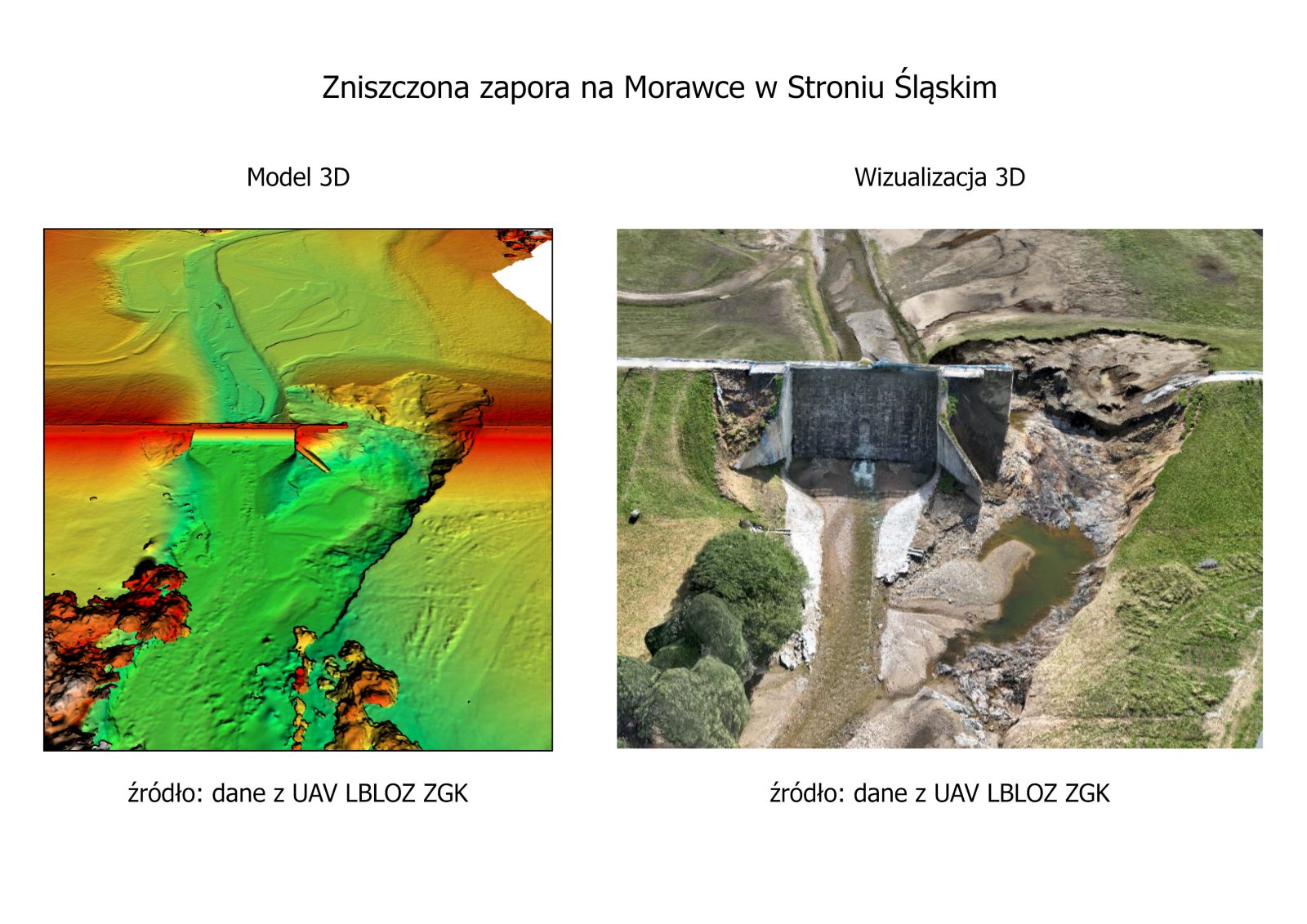

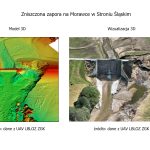

In Poland, the most tragic events took place in the eastern part of Kłodzko Land and Opole Voivodeship. Water levels on many stream gauges exceeded the absolute maxima from 1997. The situation was extremely dangerous, however, hardly anyone thought that the effects of the high water would be so catastrophic. Two dams were damaged: in Stronie Śląskie on Morawka River and Topola Reservoir, and the water from both reservoirs violently flooded the areas located below. The centers of Stronie Śląskie, Radochów, and Lądko-Zdrój were completely destroyed, the villages Trzebieszowice, Ołdrzychowice Kłodzkie, Żelazno, Kłodzko, Prudnik, and Lewin Brzeski suffered serious damage.

Since the flood wave passed through the region, we have had the opportunity to follow its enormous social and economic effects in the media. Fluvial extreme events also cause enormous changes in the natural environment. From the scientific point of view, this constitutes a huge area of interest for many scientists, especially geographers of various specialties.

First reconnaissance in documents

Immediately after the flood wave passed through – on September 16th – the geographers from Wrocław conducted the first field reconnaissance in the vicinity of the flooded Kłodzko, and the next day they already began the measurements and observations in the valleys of Biała Lądecka, Nysa Kłodzka, Wilczka, Ścinawka, and Bystrzyca Dusznicka. Since then, they have started documenting, primarily in the eastern part of Kłodzko Land, which suffered the greatest damage in the flood.

Scientists were dealing with dilemmas: ‘It may seem, in the face of such a great human tragedy, that our work is simply out of place, that it would be better to grab a shovel, put on work gloves and simply help in organizing yards, houses, or streets. Someone might say that we are disturbing the firefighters, soldiers, or police officers working in the flooded areas. However, it is the scientific work carried out simultaneously with actions performed by the services, the gaining of fundamental knowledge of the mechanisms of natural phenomena, that leads to systems, methods, and practices which can help to avoid such huge losses in the future.’

Obviously, it must be clearly stated that nothing protects us from flood in 100%. We are unable to predict the scale of some phenomena. Despite the massive amount of knowledge on the environment that we already have, despite the tools and devices which temporally allow us to harness nature, she still is and always will be stronger than us.

The team which immediately after the flood undertook the task of documenting the situation in the river beds of Kłodzko Land, on a daily basis explores the use of unmanned aerial vehicles (drones, UAV) in environmental testing. ‘Our Laboratory of Unmanned Aerial Earth Observation (LBLOZ) is equipped with a few unmanned vehicles with various measuring sensors, as well as with associated equipment used in the fieldwork. These devices provide us with a quick and precise aerial way of observing the state of the earth’s surface,’ says dr inż. Matylda Witek.

Mapping with the use of drones

The focus of the first fieldwork was to collect the most data from the biggest possible area in the shortest possible time. Drones allows for such a process of documenting without entering the flooded area, and therefore, without endangering researchers’ safety, and without interrupting the ongoing ground-based works. Our scientists conducted the aerial mapping with the use of multi-rotor drones, since they can be both lifted off from and brought down to any, even small, area free of obstacles, even the roof of a car or an operator’s “hand”. They focused on the river beds which suffered the greatest damage: Biała Lądecka, Nysa Kłodzka, and Wilczka. They also documented the places (in the vicinity of the stream gauge posts) for which they have data from the scientific projects previously conducted in Kłodzko Land.

‘The view we encountered on-site cannot be described without any emotions. Media coverage shows the extent of that tragedy, however, only when you see it with your own eyes, when you work in the area, you can truly comprehend what has happened here,’ explains dr inż. Matylda Witek, assistant professor in the Department of Geoinformatics and Cartography, head of the Laboratory of Unmanned Aerial Earth Observation.

Some team members were so surprised with the scale of the event, that they were unable to begin their work as usual. The flight designs prepared in advance had to be modified on an ongoing basis as they did not entirely cover the flooded areas. Even though our scientists know the area well, they did not expect the water to penetrate that far.

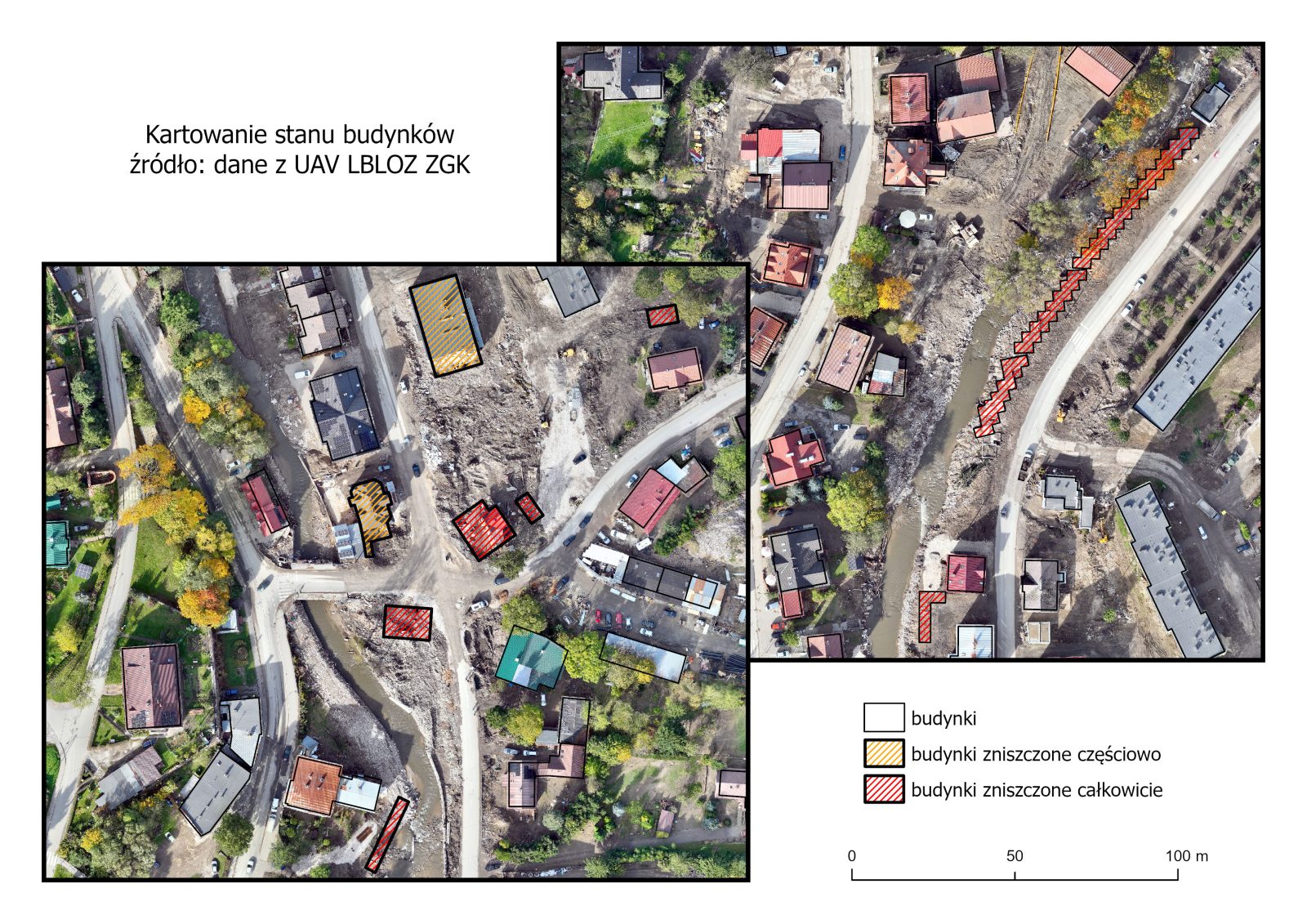

They started with the aerial mapping of the sections of the river beds selected during the reconnaissance. In the following days, when the accessibility of the area was greater (due to roads being opened, the most heavily damaged river beds being reinforced, dangerous elements being removed), they were also preparing supporting documentation, taking on-the-ground photos of morphological formations, making inventory of damaged buildings or infrastructure elements.

Documenting the effects of the flood

Environmental effects of a flood should be documented as soon after its occurrence as possible, immediately after the flooding has receded since some of its effects do not last long. Some morphological formations left behind by the flood are, basically, immediately removed, in order to ensure that people and their businesses can operate normally as quickly as possible.

Besides that, as a result of cleaning and safety works, other formations develop and their presence eradicates the readability of after-flood formations.

For a physical geographer information about localization, size, and characteristics of the morphological formations developed as a result of the high water are very important, as it is on their basis that one can draw conclusions on the workings and intensity of the river processes.

During the three weeks of work, some of the formations disappeared before the researchers’ very eyes due to the intensive works that were to restore the region’s basic functions as quickly as possible.

At the time of writing this text, LBLOZ’s equipment allowed for aerial mapping of over 30 km of the river beds affected by the flood and the places that experienced the greatest transformations.

Four people were working in the field: three workers and one doctoral student of the Department of Geoinformatics and Cartography. They flew the drones at a height of 70 m above ground in a buffer of 80 m on both sides of the river bed. They have collected almost 350 GB of raw data which is still being processed. On their basis, orthophotomaps, terrain models, and point clouds are generated and used in further analyses.

Analysis of the research material

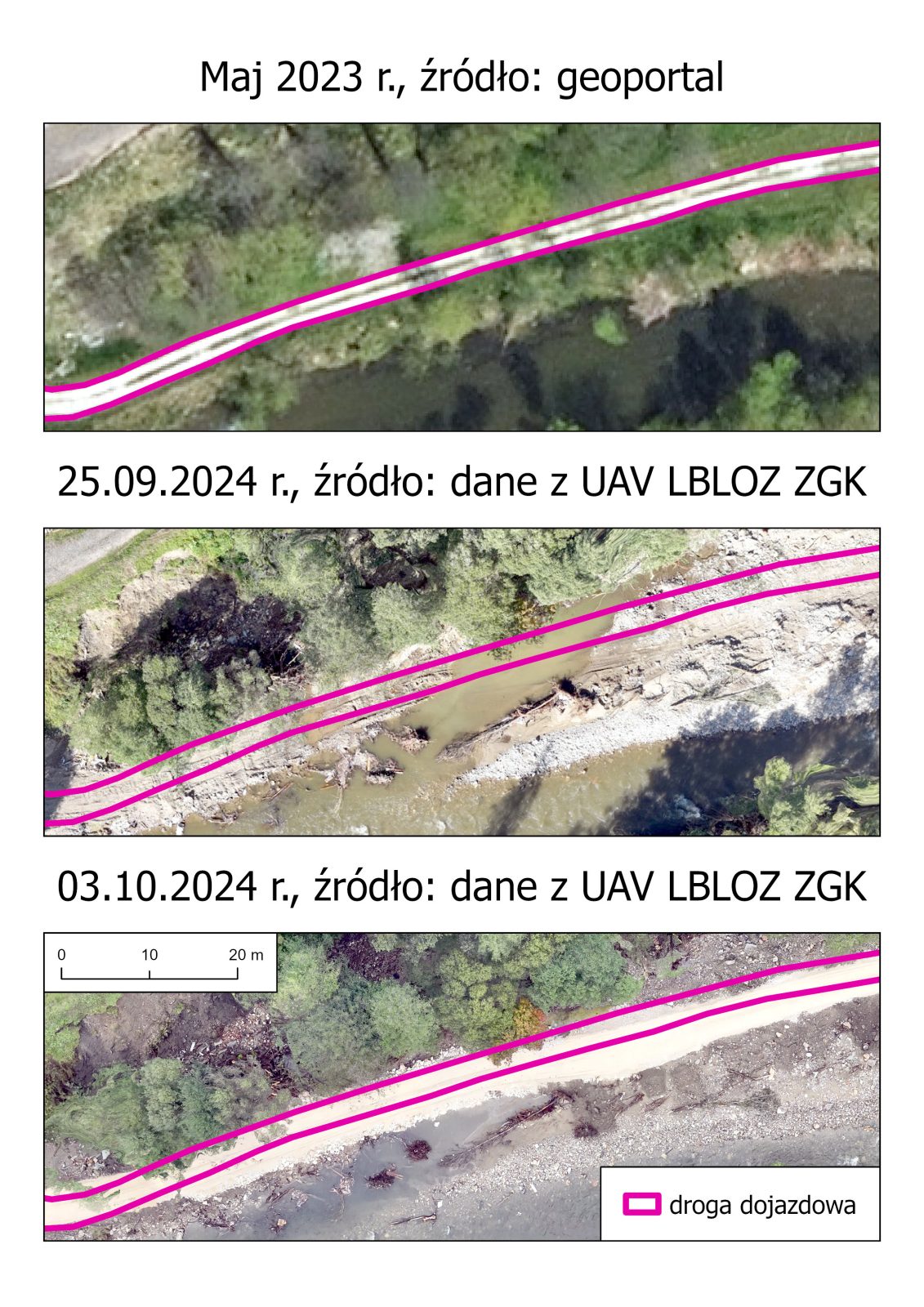

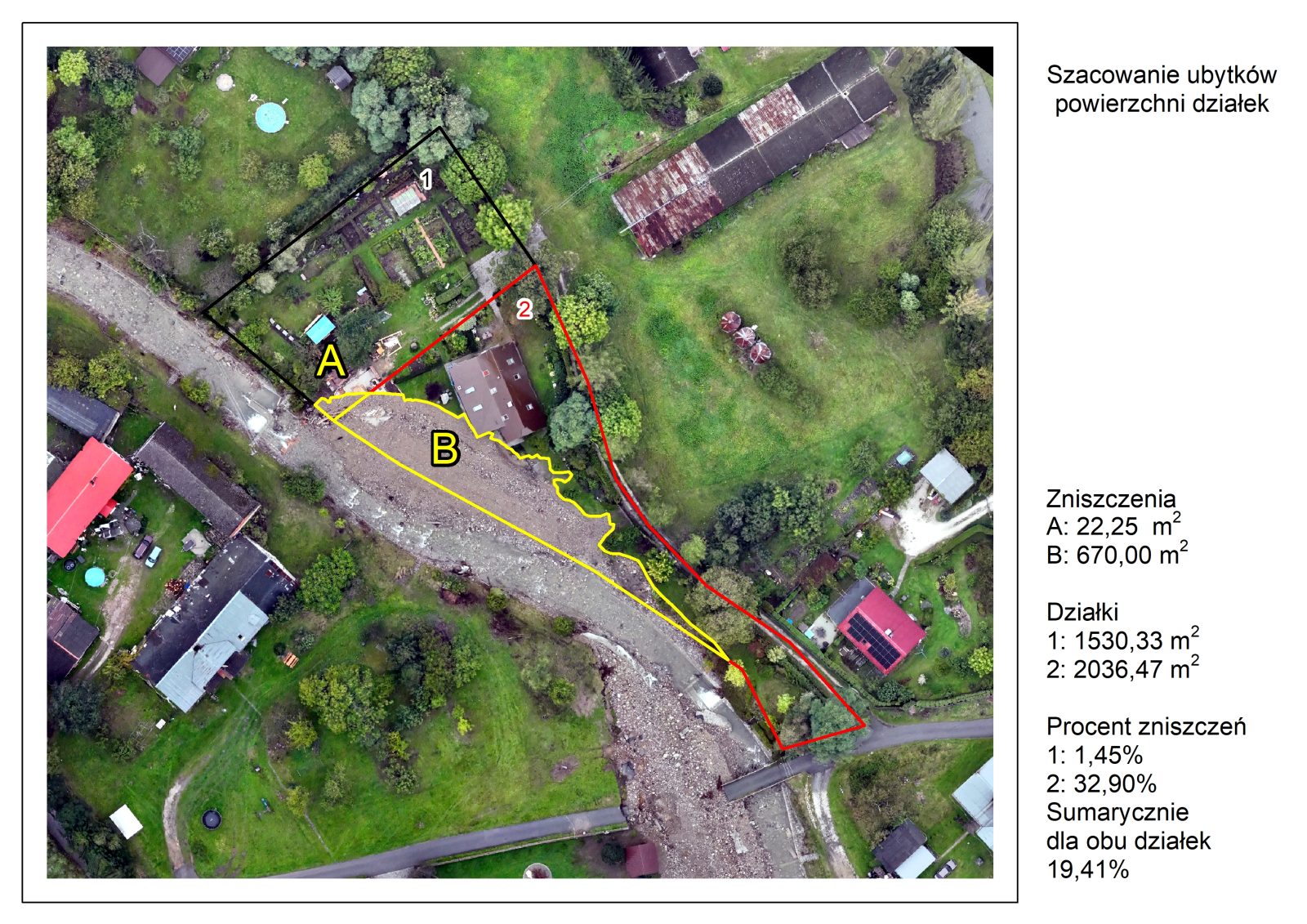

Material collected by the team serves as the basis for multifaceted analyses for both physical and social geographers as well as for researchers focusing on landscape planning. Most of all, the scientists are able to compare the morphology of the river valleys affected by the flood before and after the phenomenon took place. They are able to identify environmental effects primarily reflected in the processes of increased erosion and accumulation as well as in changes in the spatial location of the river beds caused by the high water (the phenomenon of the so-called avulsion). Analysis of the orthophotomaps allows for the inventory of the damage to infrastructure (e.g. collapsed bridges, footbridges, damaged roads) and development.

Accompanying ground-based works will supplement the data with information on damaged and condemned objects. Using the methods of image analysis, it is possible to prepare an inventory of places where the damage has already been leveled, for example, by reinforcement with the brought material. In aerial photos or orthophotomaps, such areas are clearly distinguished by a different photophone, which allows for their semi-automatic identification. In Kłodzko Land the damage to the roads, entrances to the properties, and river beds was reinforced with rock material from the quarry in Romanowo. It consisted of marbles and dolomites of light, almost white color, well visible in the aerial photos.

In many places, the floodwater “snatched away” fragments of the area, parts of the used plots of land. Applying the methods of comparative analysis, it is possible to preliminarily estimate the amount of losses. One of the fundamental uses of the materials collected by the team is to determine the extent of the flooding. In the aerial photos, in the places where the cleaning works have not yet been done, it is possible to determine the direction and the extent of flowing water. Such information can be useful when verifying whether the models forecasting flooding are working properly, and when making planning decisions in the future.

“we are just scientists”

Working in the flooded areas, the researchers experienced enormous, even surprising kindness from both the inhabitants and the services. Going into the field, they were not sure whether people would allow them to enter or whether they would hold against them that they were “observing” their destroyed homes and plots. However, nothing of the sort happened. Whomever they were talking to, the first thing they heard was: “document everything that you can, show how it really is here right now.” It was a request of not only the regular inhabitants but also representatives of organizations working for the benefit of the region. Multiple times the researchers heard: “we are glad that you are here,” which was deeply moving, especially because at the very beginning some of them simply felt bad documenting the human tragedy.

‘I think that the most memorable moment for all of us was when we were standing on the bridge in the southern boundary of Lądek-Zdrój, navigating another UAV flight, military trucks were passing us one by one, firefighters were working in the vicinity,’ says dr inż. Matylda Witek, ‘and a man approached us, the owner of the nearby guesthouse and pizza parlor which were also flooded. He took a thermal bag off from his shoulder, full of boxes with hot pizza, and told us: “you are working so hard here, so I brought you something to eat.” A colleague protested, saying: “no, no, we are just scientists, we are just documenting the state of the river bed…, offer these to soldiers and firefighters, they need it more….” And he responded: “you are all working very hard here, you need to eat, and this is the least we can do to return the favor and thank you for your help and for being here.” We were at a loss for words… We did not expect such great determination from these people, such beautiful solidarity and cooperation. The people that we met were not breaking down, they were incredibly strong and resilient, we saw in them cheerfulness and faith that it would simply be alright.’

For Matylda Witek it was especially moving as it is her Little Homeland, the land, from which she comes and to which she feels especially close.

The flood from September is no longer on the first pages of newspapers and news services, it can be said that it is a little bit forgotten already, however, for the people living in these areas, the flood’s effects are and will be present for a long time still. ‘We geographers see it similarly, we do not intend to halt our work in the flooded areas. We are planning to continue observations for at least a year, analyzing if and at what pace river systems return to the state from before the high water,’ comments Matylda Witek. ‘It is a long-term plan, but we are sure that it will bring measurable scientific results. We hope that the results of our work will be used primarily to ensure safety for people at risk of the effects of such phenomena. Please remember that the areas affected by the flood, especially those with less publicity in the media, and, primarily, the people living there, are still very much in need of our help. We must not forget about them.’

Text: dr inż. Matylda Witek, assistant professor in the Department of Geoinformatics and Cartography (ZGK), head of the Laboratory of Unmanned Aerial Earth Observation

Maps and figures: mgr Grzegorz Walusiak, doctoral student in ZGK, dr inż. Matylda Witek

Photos: dr Aleksandra Michniewicz, adjunct in ZGK, dr inż. Matylda Witek, mgr Grzegorz Walusiak – photos taken with a drone DJI Mavic 3 Enterprise

Edited by Katarzyna Górowicz-Maćkiewicz

Translated by Weronika Bogucka (student of English Studies at the University of Wrocław) as part of the translation practice.