Wrocław Dreamers – Visionary Architectural Projects from the Early 20th Century

We invite you to an exhibition showcasing Wrocław’s architectural designs that never saw realization. Inspired by an exhibition organized by the Museum of Architecture in Wrocław titled “Gdyby” (“What If“), we decided to present materials from the collections of the Wrocław University Library. These allow us to see how the city might have looked if the bold ideas of Wrocław’s best visionary architects from the early 20th century had been brought to life.

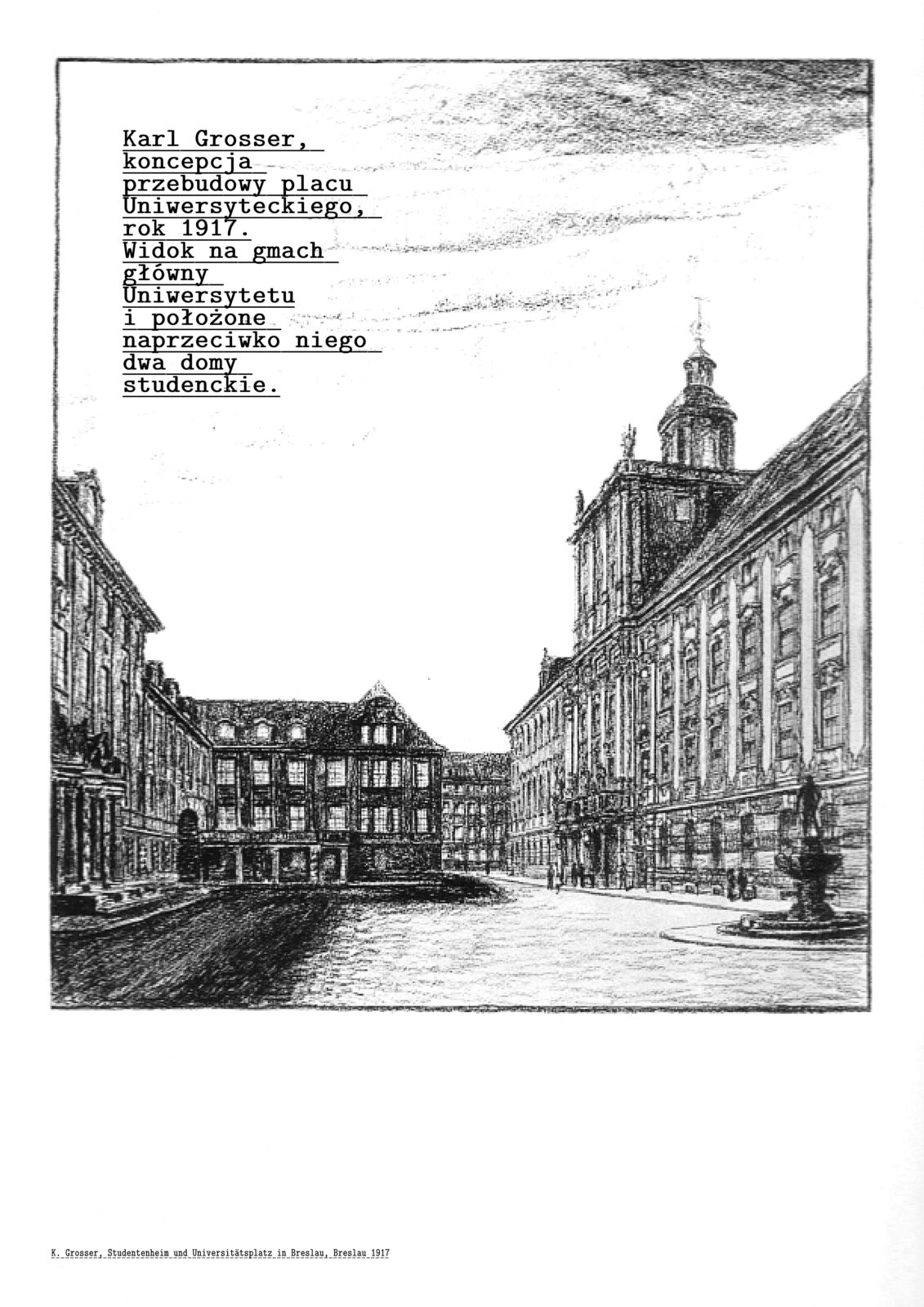

The first set of plans we wish to present concerns the current University of Wrocław building at pl. Uniwersytecki, previously occupied by the Jesuit Leopoldine Academy, which was founded in 1702. This Baroque building, with its very long facade (a shape imposed by the complicated layout of the land owned by the order) and the Mathematical Tower, faced difficult spatial, social, and material conditions from its inception. These problems intensified in the 19th century. It was noted that no other German higher education institution had such challenging conditions for work and study. The anniversary of the establishment of the first state university in Wrocław in 1911 became an impetus for change. In 1811, the Leopoldine Academy merged with the University of Frankfurt (Oder), known as Viadrina, creating the first state university in Wrocław, named Universitas litterarum Viadrina Vratislaviensis. In preparation for this anniversary, the university building underwent comprehensive renovation and modernization between 1895-1911. Anticipating the approaching jubilee, the city council also decided to reorganize the university’s immediate surroundings and in 1910 gifted the university purchased parcels at pl. Uniwersytecki on the southwest side. The gift came with conditions, including the construction of a multifunctional student house and the expansion of the current square and ul. Uniwersytecka (Ursulinerstrasse) and ul. Więzienna (Stockgasse).

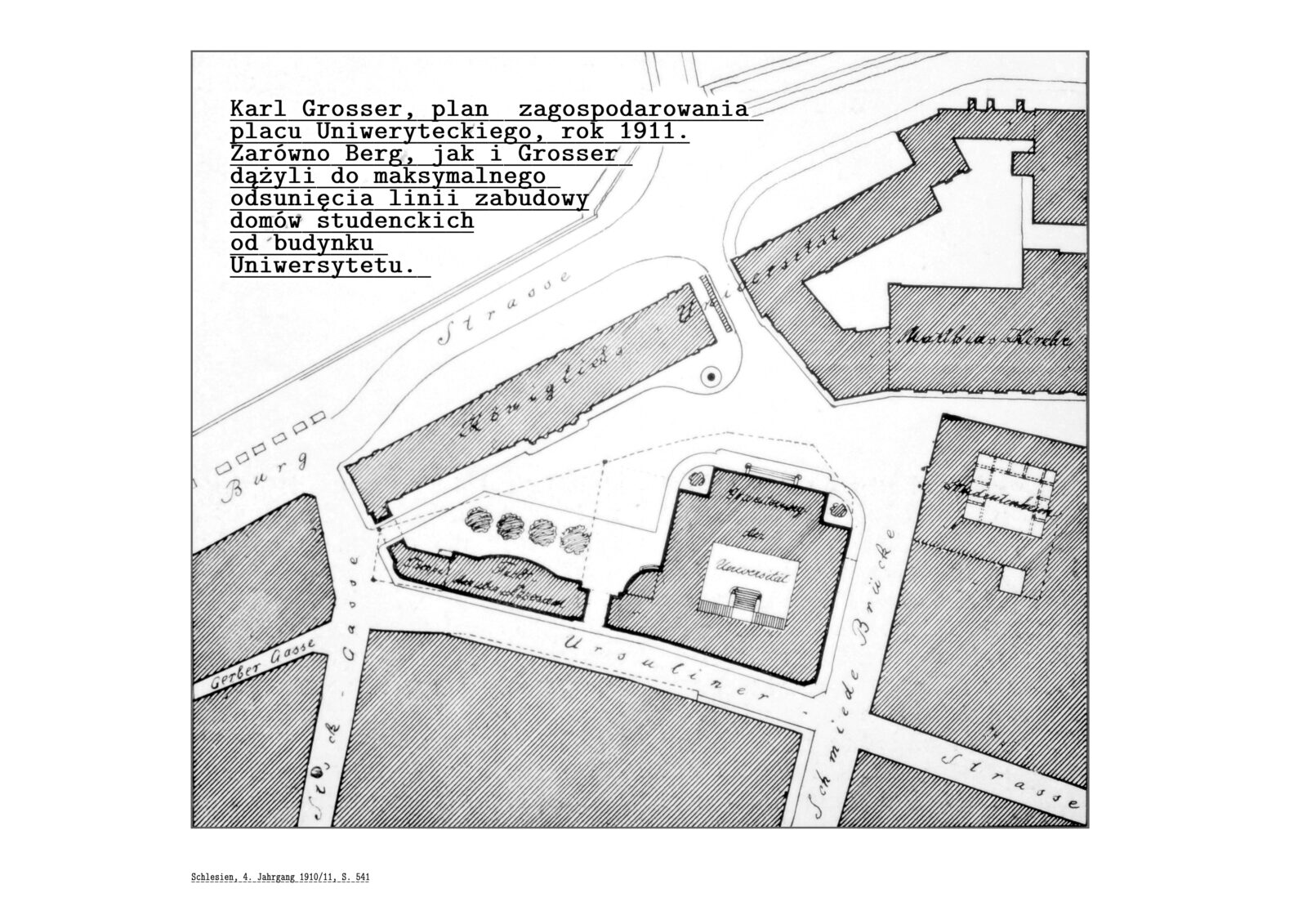

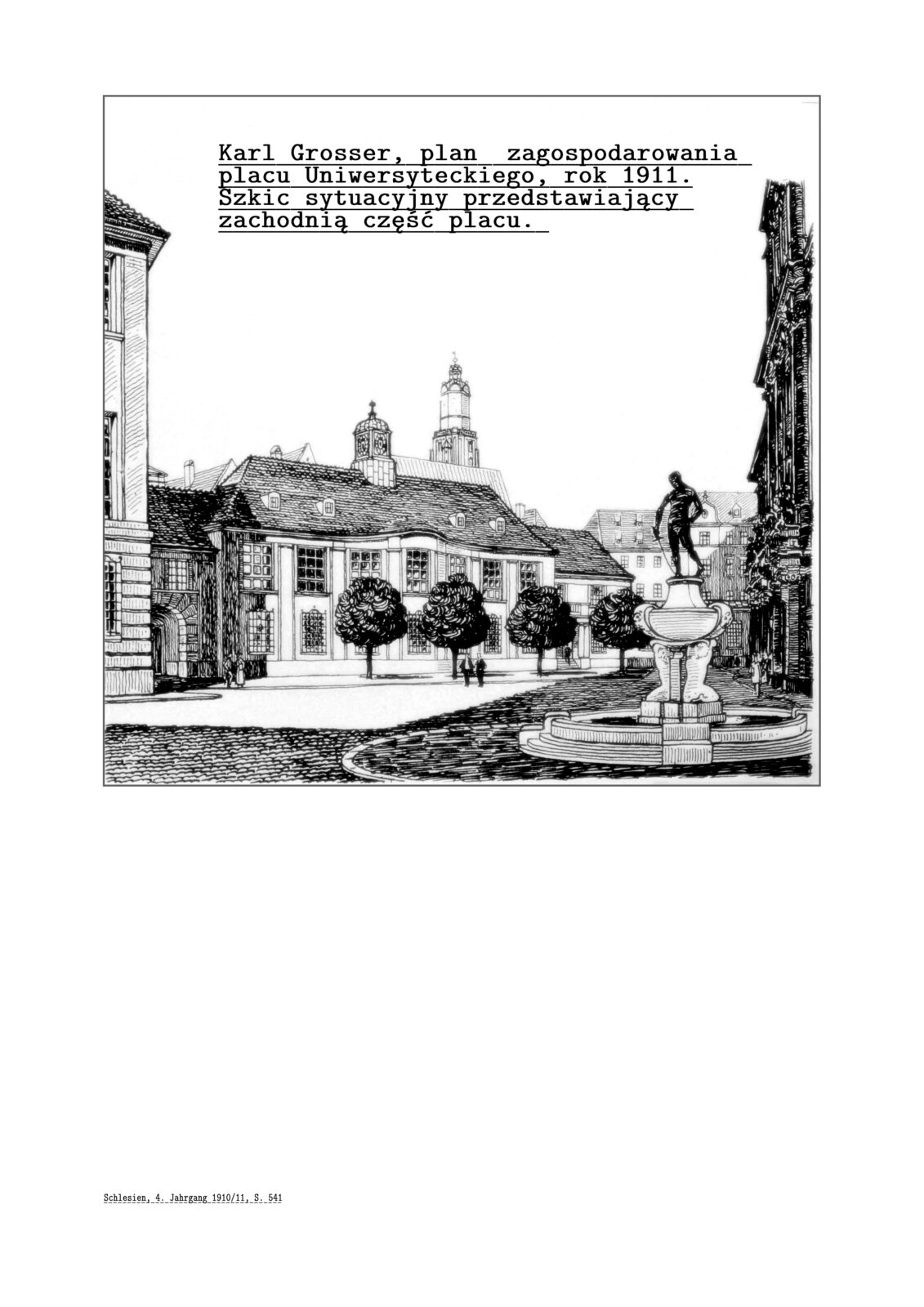

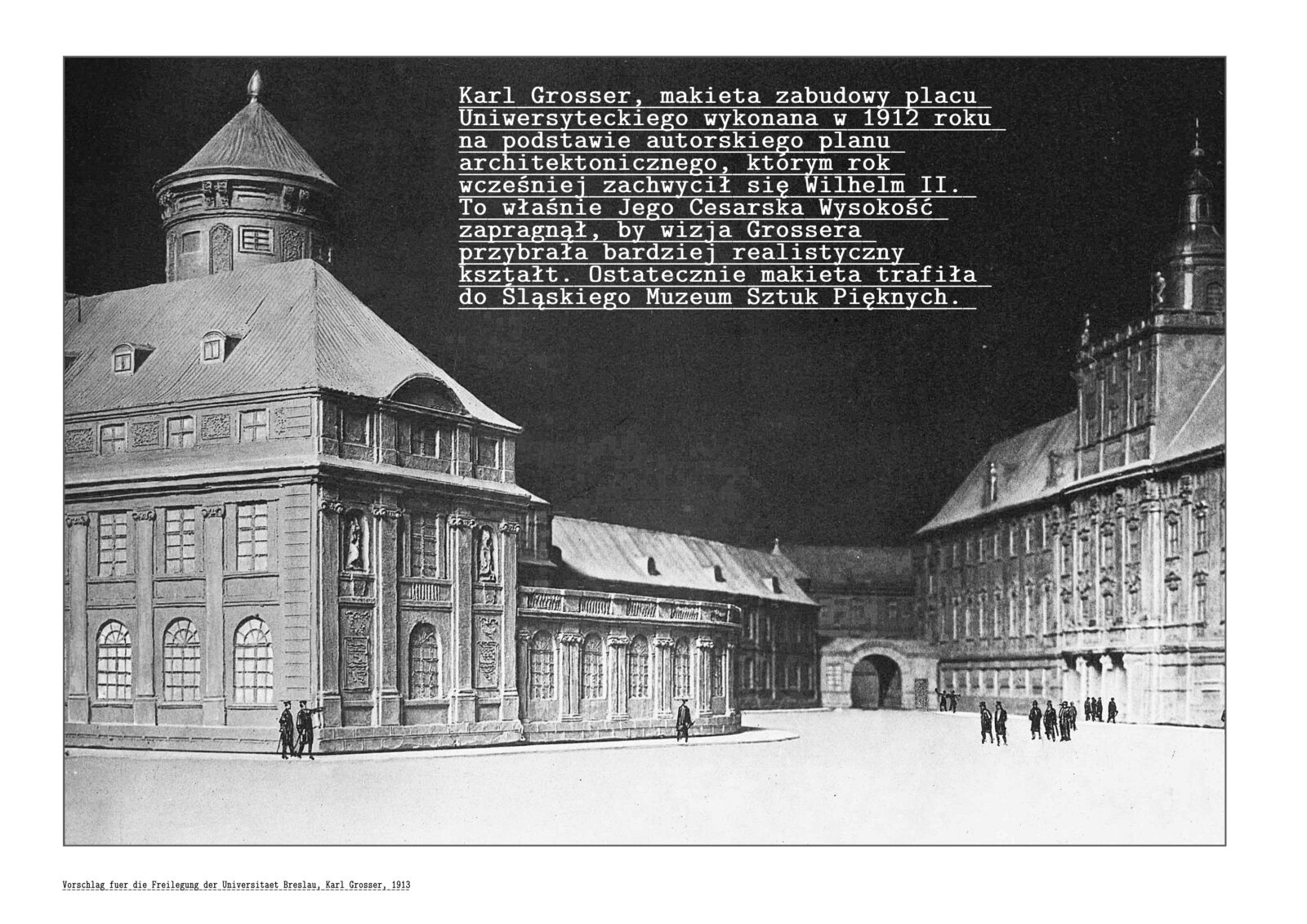

The first proposal for organizing the area around the university was presented in 1910 by Wrocław’s city building councilor, Max Berg. The architect aimed to create a fitting setting for the Baroque main building. He also sought to address the issue of the comprehensive view of the university’s long facade, caused by the building’s location at a street bend rather than on a main visual axis. Another concept for pl. Uniwersytecki development was proposed by Wrocław architect Karl Grosser in 1911, and in 1912, at the request of Wilhelm II Hohenzollern, he personally created models of the existing and planned buildings at pl. Uniwersytecki. He presented them to the ruler, and later to the residents of Wrocław and Berlin. Despite the architects’ efforts, the plans for pl. Uniwersytecki redevelopment were never realized. Karl Grosser tried again in 1917, and Max Berg, along with Albert Kempter, in 1918. The idea resurfaced in 1936 on the 125th anniversary of the university’s founding but was also never executed.

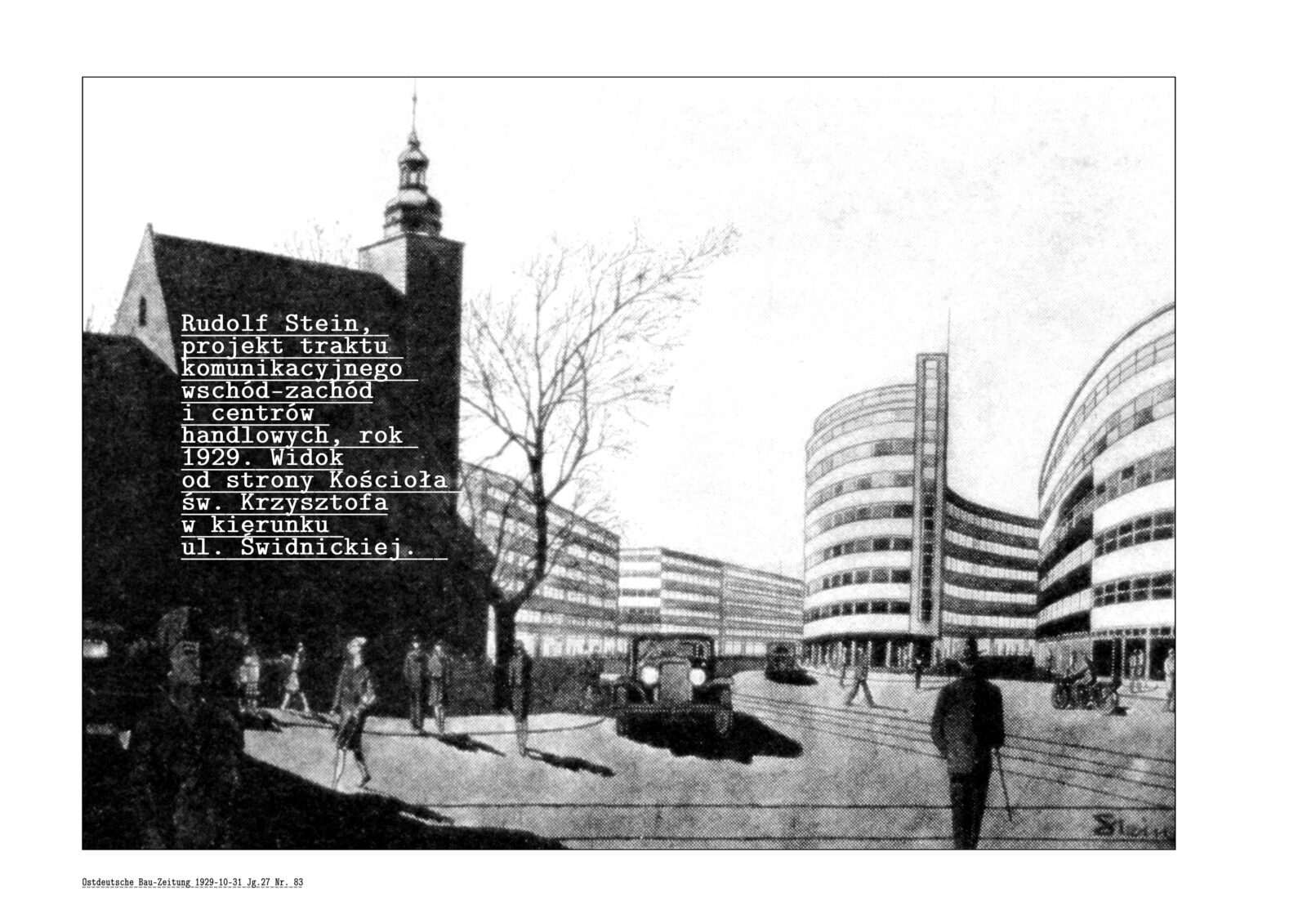

The second group of early 20th-century projects worth presenting is related to the city’s urban challenges, which had been worsening since the early 19th century. The built-up area did not increase proportionally to the population growth. City authorities initiated several actions to improve living conditions, including significantly expanding the city limits. However, this proved insufficient. Further changes were halted by the very difficult economic and financial situation following World War I. Many new ideas remained on paper, while some were realized much later. Almost all architects working in Wrocław at the time, as well as creators from other parts of Germany, participated in the city’s organized competitions.

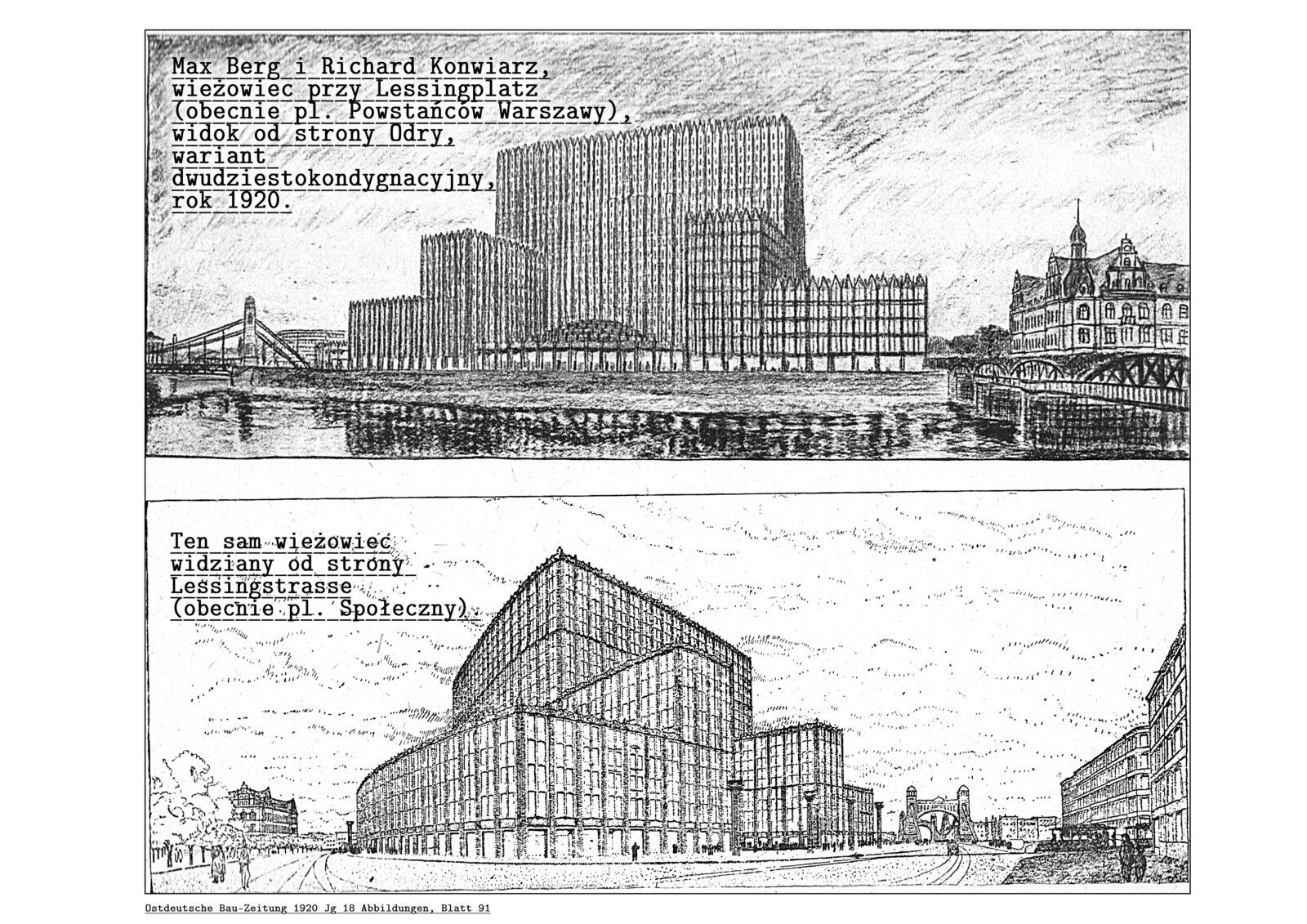

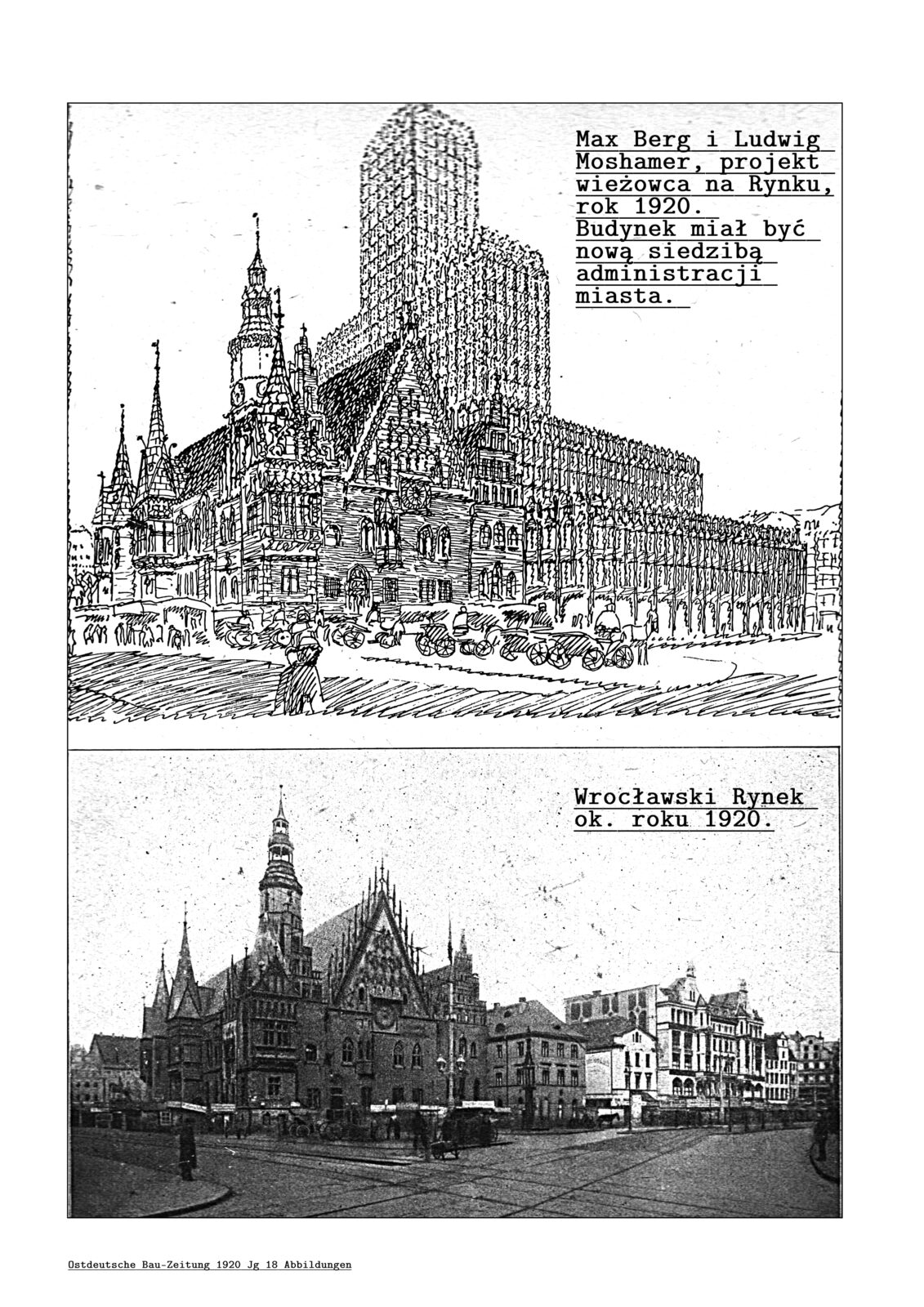

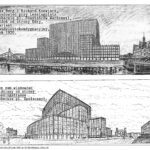

It is impossible to overlook one of Europe’s most outstanding architects, Max Berg, who served as Wrocław’s city building councilor. He devoted much time and effort to solving the city’s urban problems. Between 1919-1921, Max Berg, along with Ludwig Moshamer and Richard Konwiarz, prepared a project for changes in the city center according to modern urban planning principles. They proposed, among other things, changing the main railway routes and redesigning the city’s transport layout by widening and reconstructing streets. Berg was the first German architect to consider the possibility of alleviating housing problems, exacerbated after World War I, through the construction of skyscrapers. His visionary plans included creating satellite towns around Wrocław, approximately 30 km from the center. Berg designed the first skyscraper projects in 1919, and in June 1920, he presented plans for four office buildings at an exhibition organized by Künstlerbund Schlesien and the Wrocław Akademia Sztuki i Rzemiosła Artystycznego (Academy of Art and Applied Arts). These were office buildings in the Town Square, ul. Tęczowa (Siebenhufenerstrasse), ul. Podwale (Am Schweidnitzer Stadtgraben), and pl. Powstańców Warszawy (Lessingplatz). Each building was to serve a different purpose. Berg’s skyscrapers were one of the first attempts in Europe to transplant American concepts onto the old continent. The architect compared this type of construction to Gothic cathedrals and parish church towers. However, Berg’s projects were rejected.

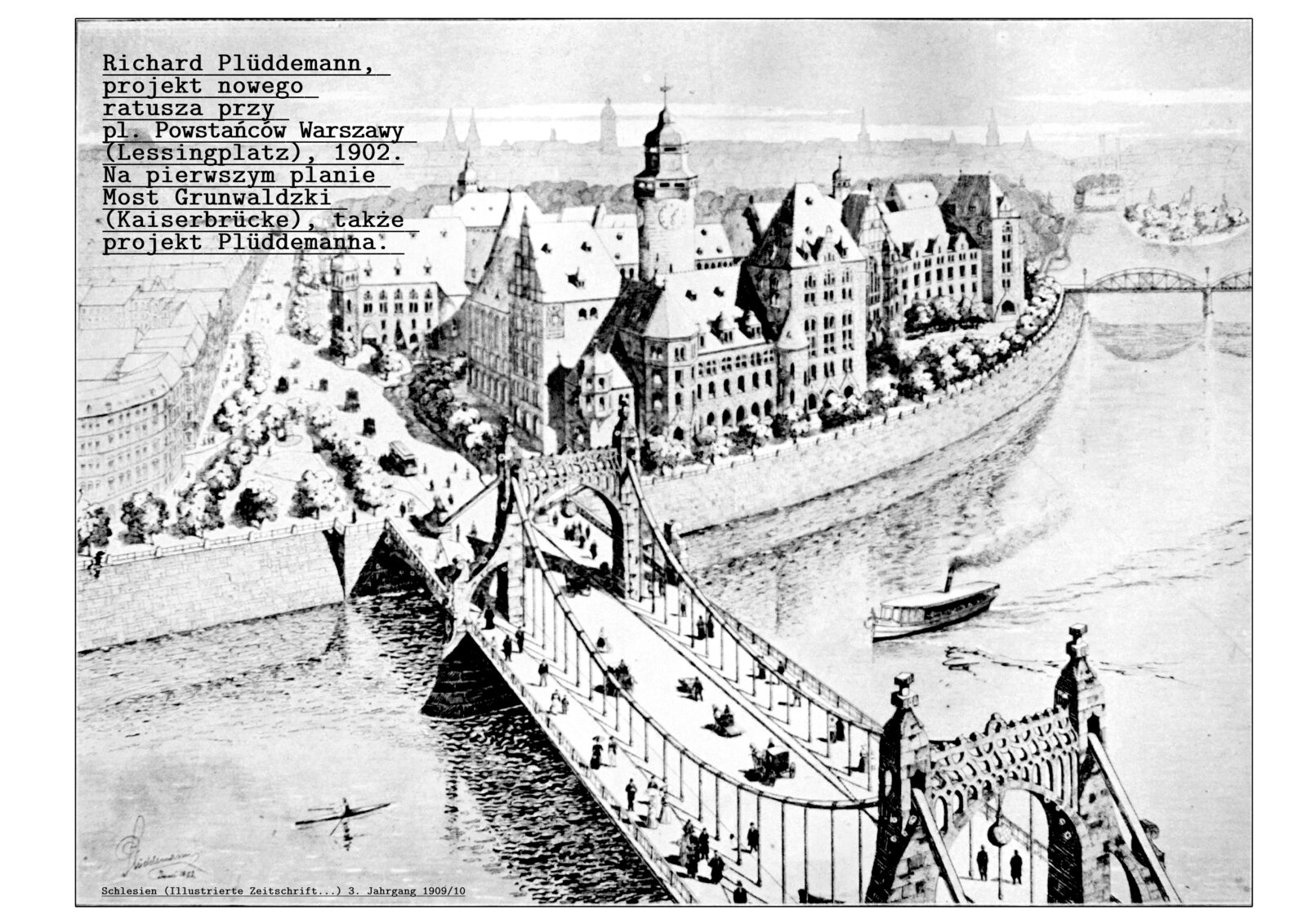

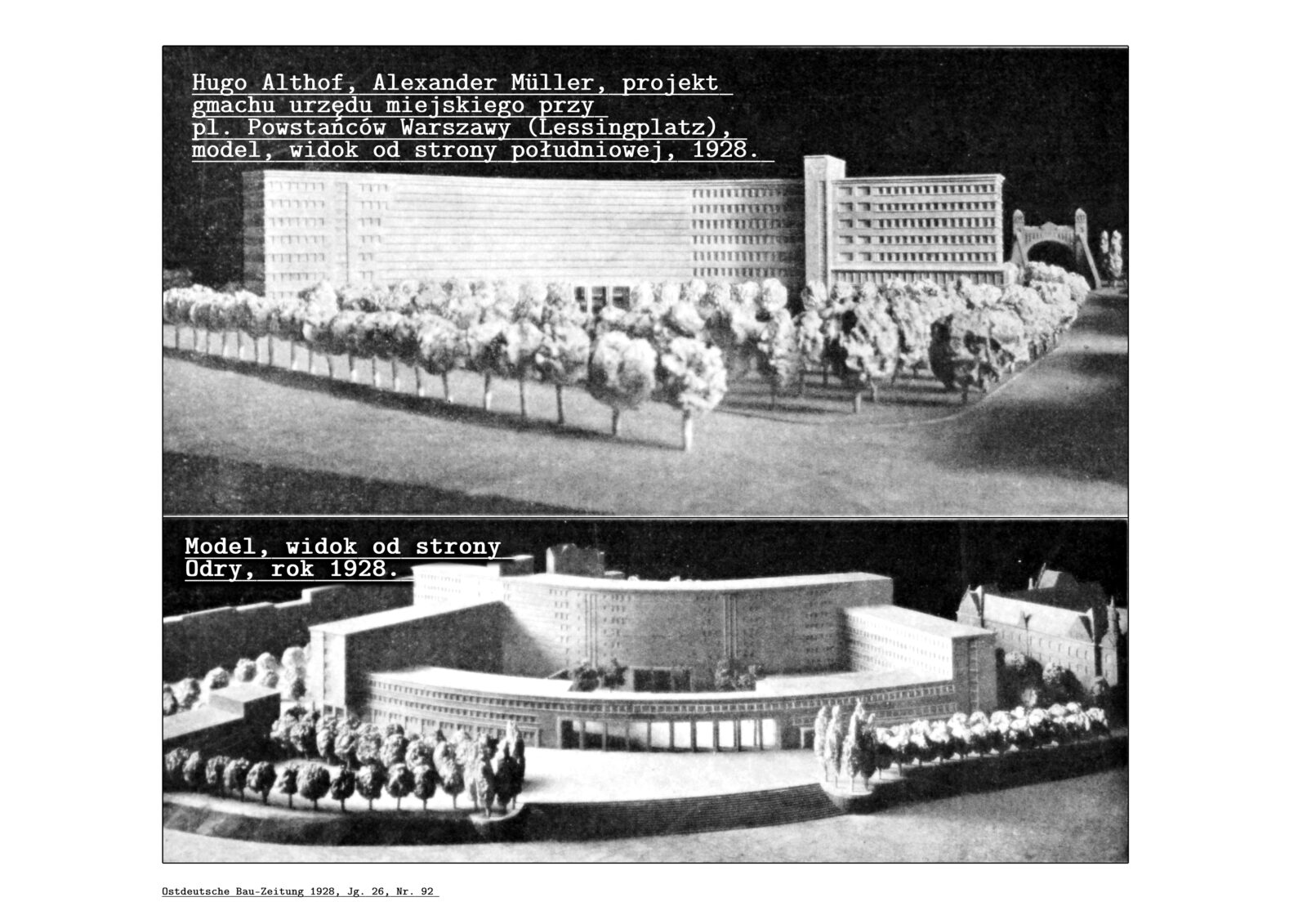

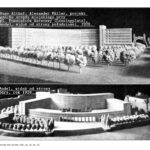

The need for city expansion and the growth of municipal administration drew attention to the current pl. Powstańców Warszawy (Lessingplatz), located relatively close to the center. The plan was to demolish the unused gasworks here and build a new headquarters for the expanding municipal administration and a new Most Cesarski, or Emperor’s Bridge (now Most Grunwaldzki). As early as 1896, architect Richard Plüddemann proposed, in his lecture and a 1909 article, the construction of a new city hall in this area. Another concept for the new city hall at pl. Powstańców Warszawy was presented by Max Berg and Richard Konwiarz (1919-1920). A subsequent competition for a new city hall project with a fire station was announced in 1927. The first prize was not awarded, but the second prize went to the authors of two projects: Wilhelm Deffke from Berlin and Aleksander Müller from Würzen and Ferdinand Schmidt from Dresden. After much discussion, the 1928 winning project for the new city hall by then-building councilor Hugo Althoff and Alexander Müller was accepted for implementation. However, these plans were also not realized. Felix Bräuler, the author of the current Voivodeship Office building, which began construction in 1939, utilized spatial solution concepts from earlier competition plans.

The exhibition is displayed in showcases next to the Special Collections’ Reading Room on the 3rd floor of the Wrocław University Library. It will run until the end of June and can be visited during library hours. We warmly invite you to attend.

Marta Lange

Translated by Oliwia Kowalińska (student of English Studies at the University of Wrocław) as part of the translation practice.